MIKE TRUSSON has spent a lifetime in football since Plymouth Argyle spotted his raw teenage talent, took him on as an apprentice and gave him his professional debut at 17.

After playing more than 400 matches over 15 years, he became prominent in football marketing, coaching and scouting, often in association with his good friend Tony Pulis, who he played alongside at Gillingham after leaving the Albion.

As recently as late 2020 he was assistant manager to Pulis for an ill-fated brief spell at Sheffield Wednesday.

Much fonder memories of his time in the steel city were forged when he was twice Player of the Year at Sheffield United.

In an exclusive interview with the In Parallel Lines blog, Trusson told Nick Turrell about his time with the Seagulls, his first coaching job at AFC Bournemouth and the formative years of his career.

A MOVE TO SUSSEX in the summer of 1987 ticked all the right boxes for Mike Trusson.

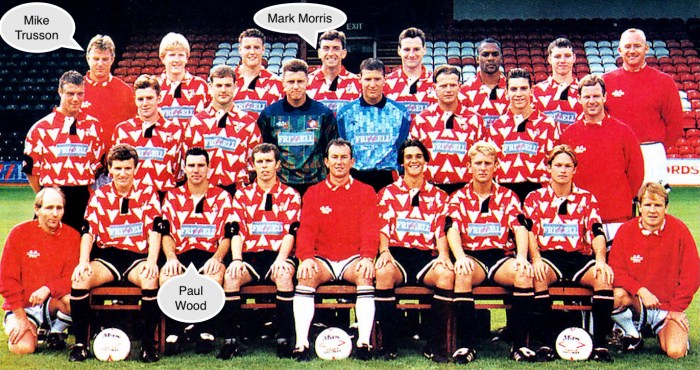

An experienced midfielder with more than 300 games under his belt already, he welcomed the opportunity to be part of the rebuilding job Barry Lloyd was undertaking at the Goldstone following the club’s relegation back to the third tier. He was one of seven new signings.

The move also brought him a whole lot closer to his family in Somerset than south Yorkshire, where he’d lived and played for seven years.

And it gave him the chance to earn more money.

The only problem was he had a dodgy left knee – it was an injury that prevented him making his first team debut for the Seagulls for four months, and it troubled him throughout his first season.

Frequent leaping to head the ball had resulted in a torn patella knee tendon that had needed surgery during the latter days of the player’s time at Rotherham United, where for two years his manager had been the legendary former Leeds and England defender Norman Hunter.

Prior to the injury, Blackburn Rovers had bid £200,000 to sign him, but nothing came of it and a contractual dispute with the Millers (who were not keen to give him what he said he was entitled to because of the injury) led to him being given a free transfer (Hunter subsequently signed former Albion midfielder Tony Grealish).

Trusson fancied a move south to be nearer his folks and had written to several clubs, Albion included, who he thought might be interested in his services (these were the days before agents).

Although Millwall and Gillingham had shown an interest, it was a call from Martin Hinshelwood, Lloyd’s no.2, that saw Trusson head to Sussex for an interview where he met the management pair, chairman Dudley Sizen and director Greg Stanley.

Trusson looks back on the encounter with amusement because not only did they agree to take him on but they offered him more money than he was asking for because they said he’d need it in view of the North-South disparity in property prices.

“Brighton was a big club. Only four years earlier they’d been in the Cup Final and some of those players from that time were still at the club,” he said. “From my point of view, it was a big career move. It ticked all the boxes.”

Initially Trusson shared a club house in East Preston with fellow new signings Kevin Bremner, Garry Nelson and Doug Rougvie before moving his wife and daughter down and settling in Angmering, close to the training ground (Albion trained at Worthing Rugby Club’s ground at the time).

Before he could think about playing, though, he had to get fit. Scar tissue after the operation on his knee had left him in a lot of pain, and although he passed his medical, the pain persisted.

New physio Mark Leather told him straight that he wouldn’t be able to train, let alone play, with the leg in the condition it was. It had shrunk in size due to muscle wastage so his first two months at the Albion were spent building it back up and regaining match fitness in the reserves.

In the meantime, former full-back Chris Hutchings was keeping the no.8 shirt warm until he finally got a move to Huddersfield that autumn.

Trusson recalled: “I was aware there was a rebuilding process going on. It was a very different group to ones I’d experienced at other clubs. A lot of the lads travelled down from London so there was not much socialising.”

There was certainly lots of competition for places during his time at the club. Sometimes Dale Jasper would get the nod over him and he could see Lloyd preferred the ball-playing types like Alan Curbishley and Dean Wilkins, and later Robert Codner and Adrian Owers.

“I thought if I was going to play, I had to change,” Trusson reflected. “I became more of a midfield enforcer and left it to the better players to play.”

As such, he was surprised yet delighted to score on his home debut, albeit, more than 30 years on, he doesn’t remember much about it.

For the record, it was on 12 December 1987, in front of a rather paltry 6,995 Goldstone Ground crowd, that Trusson scored the only goal of the game against Chester City as Albion extended an unbeaten run to 15 matches. (Chester’s side included former Albion Cup Final midfielder Gary Howlett, who was on loan from Bournemouth).

In that injury-affected first season, he played 18 games plus seven as sub. He had been on the subs bench for three games as the season drew to an exciting climax, but he was not involved in the deciding game when Bristol Rovers were beaten 2-1 at the Goldstone.

When the 1988-89 season got under way, Trusson was on the bench for the first two league games and he got a start in a 1-0 defeat away to Southend in the League Cup. After the side suffered eight defeats on the trot, Trusson was back in the starting line-up for the home game v Leeds on 1 October and Albion chalked up their first win of the season (1-0).

Unsurprisingly, Trusson kept his place for the next clutch of games, although Curbishley returned and kept the shirt for an extended run.

It wasn’t until the new year that he won back a starting place but then he had his best run of games, keeping the shirt through to the middle of April.

The previous month he was sent off (above) in the extraordinary match at Selhurst Park which saw referee Kelvin Morton award five penalties in the space of 27 minutes, as well as wielding five yellow cards and Trusson’s red. Four of the penalties went to Palace – they missed three – but they went on to win 2-1 against the ten men. Manager Lloyd said: “I don’t think I’ve ever been involved in such a crazy game – we could have lost 6-1 but were unfortunate not to gain a point.”

Looking back, Trusson reckoned: “I was always conscious I wasn’t Barry’s type of player.” With a gentle but respectful sense of understatement, he said: “He was not the most communicative person I have met in my life!”

In essence, perhaps not surprisingly, Trusson would seek an explanation as to why he wasn’t playing when he thought he deserved to, but it wasn’t always forthcoming. He recalled that defender Gary Chivers, who he was reunited with at Bournemouth and who he stays in touch with, used to call Lloyd ‘Harold’ after the silent movie star!

Nevertheless, he said: “Tactically Barry was a good manager. When he did talk, he talked a lot of sense.”

It was during his time at Brighton that Trusson started running end-of-season soccer schools for youngsters. He was honest enough to admit they gave him an opportunity to earn a bit of extra money to put towards a holiday rather than laying the foundations for his future career as a coach.

That was still a little way off when, at 29, he left the Albion in September 1989 having played 37 games. By then, Curbishley, Codner and Wilkins were firmly ensconced as the preferred midfield trio, and he wanted to get some regular football. Cardiff wanted him but his family were settled in West Sussex so he opted for Gillingham, which was driveable, although he stayed in a clubhouse the night before matches.

It was at Priestfield where he began to establish a close friendship with Tony Pulis, who was winding down his playing career and was similarly commuting to north Kent (from Bournemouth).

“We had always kicked each other to bits when we played against each other but often ended up having a drink and a chat afterwards, and got on,” said Trusson. “We were also keen golfers, and both talkers; we had our views (even if we didn’t always agree) and the friendship developed.”

This is a good point to go back to the beginning because it was his early appreciation of the art of coaching that would ultimately become the foundation for what followed later.

Born in Northolt on 26 May 1959, Trusson had trials with Chelsea as a schoolboy but a bout of ‘flu put the kibosh on any progress. It also wasn’t helped by the family relocating to Somerset, not a renowned hotbed for nurturing football talent.

The young Trusson went to Wadham Comprehensive School in Crewkerne and his hopes for another crack at professional football were given a huge boost when a Plymouth Argyle vice-president, who was involved with the local youth football side he played for, organised for him to have a trial at Home Park.

Argyle liked what they saw and offered him an apprenticeship, and the excellent greensonscreen.co.uk website details his career in the West Country.

It was Trusson’s good fortune that former England goalkeeper Tony Waiters – a coach ahead of his time – was Argyle boss and he gave him a first team debut aged just 17 in October 1976.

Waiters was a great believer in giving youngsters their chance to shine at an early age; he’d already worked for the FA as a regional coach, for Liverpool’s youth development programme, and been manager of the England Youth team, before being appointed Argyle manager. He later went on to manage the Canadian national team at the 1986 World Cup.

Waiters and his assistant Keith Blunt, who later took charge of the Spurs youth team in the 1980s (and was technical director at the English National Football School at Lilleshall between 1991 and 1998) together with Bobby Howe, the former West Ham and Bournemouth defender, completely opened Trusson’s eyes to what could be achieved through good coaching.

“They were in the vanguard of English coaching in the mid to late ‘70s,” he said. “I joined Plymouth as a kid having never been coached. Growing up in Somerset, we just used to play games.

“From when I was 15 to 17, they taught me so much, talking me through so many aspects of the game, and coaching me to understand why I was doing certain things on the pitch, giving advice about things like timing and angled runs.”

In an Albion matchday programme interview, Trusson told reporter Dave Beckett: “They kept us in a youth hostel and looked after us really well, even providing us with carefully planned individual weight and fitness programmes.

“Certainly you couldn’t fault them on their ideas. Out of the 20 apprentices I knew brought on by the scheme, 17 made the grade as pros. That’s an astonishingly high return by anybody’s standards.”

Although Argyle were relegated in his first season, Trusson kept his place under Waiters’ successors in the hotseat: Mike Kelly, Lennie Lawrence and Malcolm Allison. Bobby Saxton was in charge by the time he left Plymouth in the summer of 1980 to join then Third Division Sheffield United.

He was signed by Harry Haslam but, halfway through a season which it was hoped would see Blades among the promotion contenders, things went horribly wrong when Haslam moved ‘upstairs’ and former World Cup winner Martin Peters took over the running of the team. United were relegated to the fourth tier for the first time in their history.

Peters and Haslam quit the club and former Sunderland FA Cup Final matchwinner Ian Porterfield, who had just won the Division Three title with Rotherham, took charge.

Blades bounced straight back as champions, losing only four games all season, and Trusson was their Player of the Year. He earned the accolade the following season as well, when they finished 11th in Division Three.

The side’s prolific goalscorer at that time, Keith Edwards, a former teammate who now works as a co-commentator covering Blades matches for Radio Sheffield recently told the city’s daily paper The Star: “He was such a likeable character in the dressing room.

“I had a great understanding with him. He was a great team man, good for the dressing room and could play in a lot of positions. Every now and then he got himself up front with me and he worked his heart out.

“He looked after you as a player, he could be a tough lad. We played Altrincham one week and he got sent off for whacking someone that had done me a previous week. He was handy.

“And he was such a good character to have in the team.”

After three years at Bramall Lane, and 126 appearances, (not to mention scoring 31 goals), he was then swapped for Paul Stanicliffe and, instead of involvement in a promotion bid, found himself in a relegation fight at Rotherham United.

Trusson enjoyed his time with the Millers under George Kerr and over four years he played 124 games and chipped in with 19 goals. It was a regime change, and the aforementioned injury, that saw life at Millmoor turn sour.

A brief spell playing for Sing Tao in Hong Kong followed the end of his time with Gillingham and on his return to the UK his pal Pulis, who had taken over as Bournemouth manager from Harry Redknapp, invited him to become youth team coach at Dean Court.

“I loved it and, when David Kemp moved on, I got the opportunity to coach the first team,” he said.

“We were very young and we were struggling to avoid relegation,” he recalled. “We kept them up and it was great experience. We both learned so much and we spent a lot of time together.”

When Pulis was sacked, Trusson was staggered to be offered the job as his replacement but turned it down out of loyalty to his friend.

The pair have since worked together at various clubs. For example, he was a senior scout at Stoke City and head of recruitment at West Brom.

“I’ve worked for him as a scout at pretty much every club he’s been at,” said Trusson, who cites trust, respect and judgement as the attributes Pulis saw in him.

Trusson was also once marketing manager for football-themed restaurant Football, Football in London – he managed to woo Sean Bean, the actor who is a well-known Blades fanatic, to the opening – and he had a marketing job for the PFA.

He runs his own online soccer coaching scheme and was working as a European scout for Celtic when, in an unexpected return to football’s frontline in November 2020, he was appointed assistant manager of Sheffield Wednesday.

Pulis replaced Garry Monk at Hillsborough and turned to Trusson as his no.2. In that interview with The Star, Edwards said: “He’s a great lad. I was slightly surprised to see him get the job at Wednesday, but it was completely understandable.

“He’s a clever bloke, knows his football and has stayed in the game all this time, which is to his credit. His experience of scouting, coaching and having played in several different positions makes him a massive asset to any football club, I’d say.”

Edwards recalled how his former teammate had an eye for coaching from a young age. “He was always keen to get into that, he always wanted to lend a hand to the coaches,” he said.

“Some players would get off as quickly as they could to their families or whatever they were doing with their time. He wasn’t like that, he bought into the club thing. Some players were always around the place and he was like that, very understanding and willing to help out.

“I had massive fall-outs with the odd person, you know how it is, but I never saw Truss like that. He was always so calm and understanding of other people’s opinion. That’s how and why he’s stayed in the game throughout all this time. That either comes naturally to you or it doesn’t.

“I remember he always had a way of talking to people, whether that’s players or fans or board members or coaches. That’s stuck with him today.”

4 thoughts on “A lifetime in football for Mike Trusson the enforcer”