IAN MELLOR became a hero strike partner to the mercurial Peter Ward at Brighton after beginning his professional career at Manchester City.

Mellor, who I first featured in this blog in 2016, died in 2024 aged 74 from amyloidosis, a rare disease which also afflicted City legend Colin Bell.

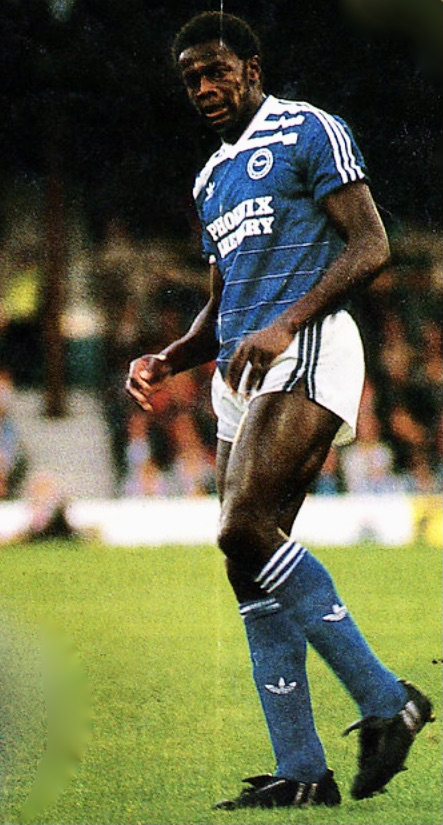

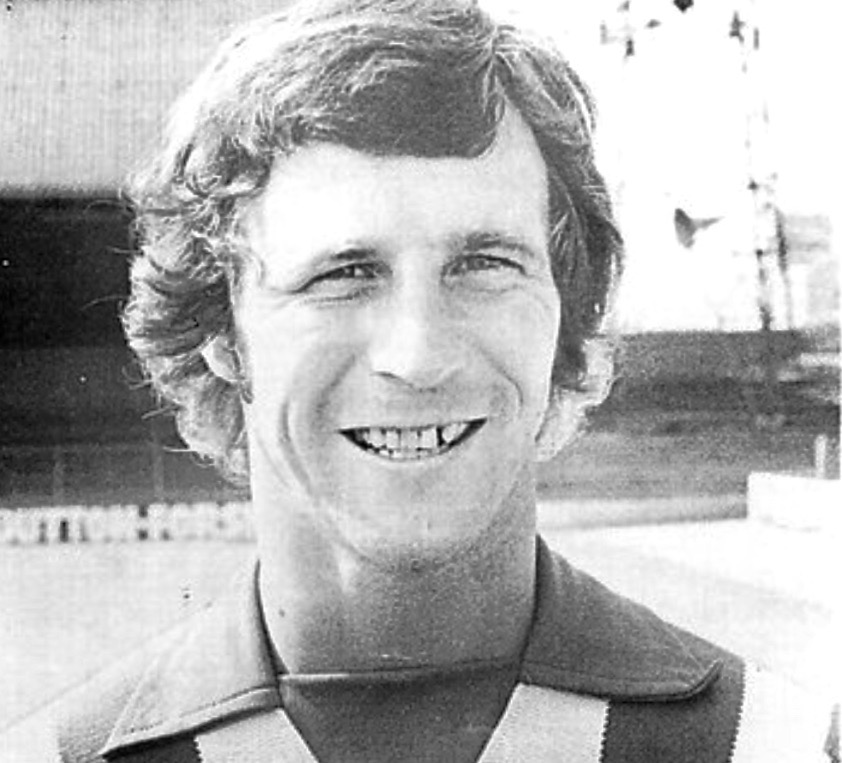

Affectionately known as Spider because of his thin, long legs, it was a nickname given to him by City goalkeeper Ken Mulhearn who playfully likened him to the Spiderman character players would watch on TV if away in a hotel on a Saturday morning before a game.

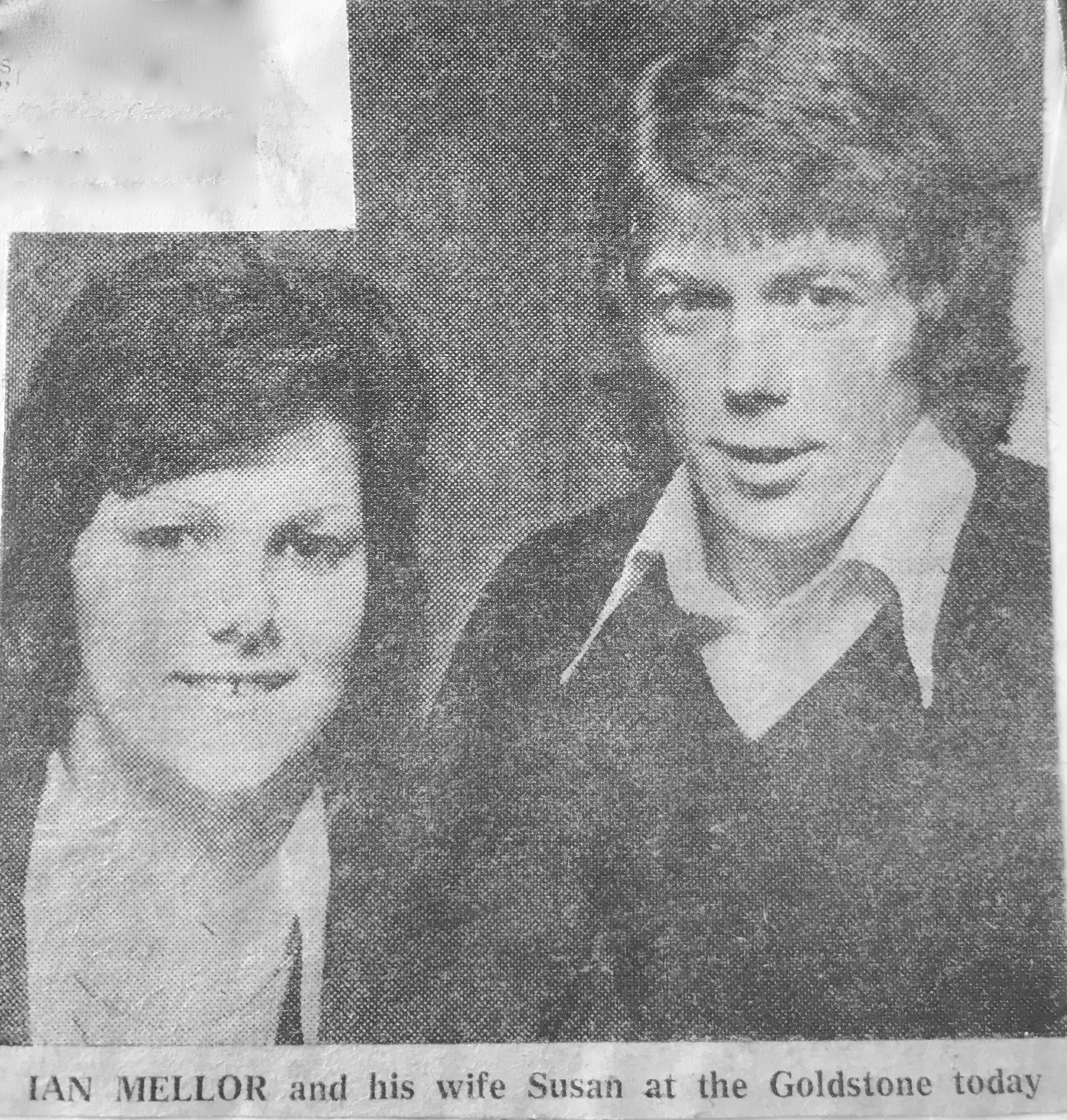

Signed for Brighton by Brian Clough for what at the time was a record £40,000 fee for the club (fellow Norwich youngsters Andy Rollings and Steve Govier joined at the same time), the opinionated manager had quit for Leeds before Mellor had kicked a ball in anger for the Albion.

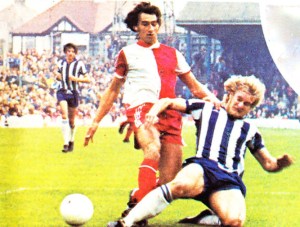

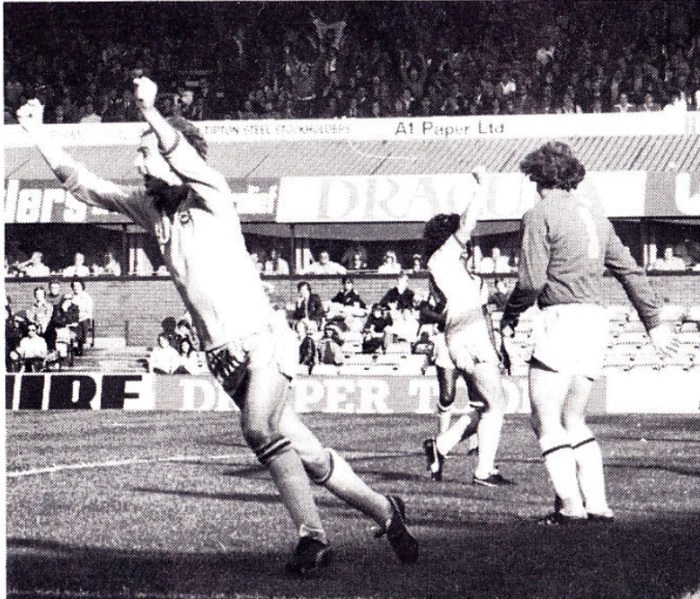

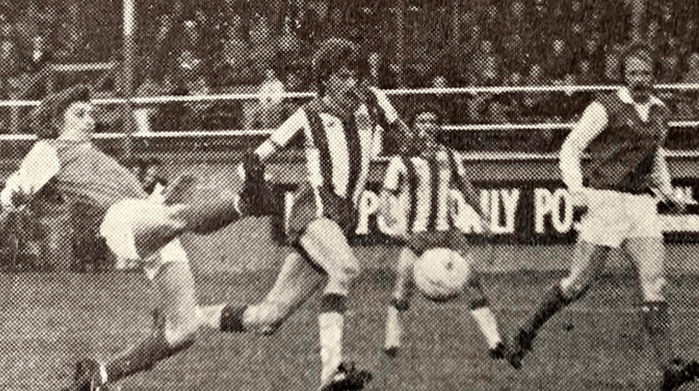

Clough’s sidekick Peter Taylor stuck around for two seasons and Mellor made a goalscoring start for him, netting against his old boss Malcolm Allison’s newly-relegated Crystal Palace side in the season’s opening game.

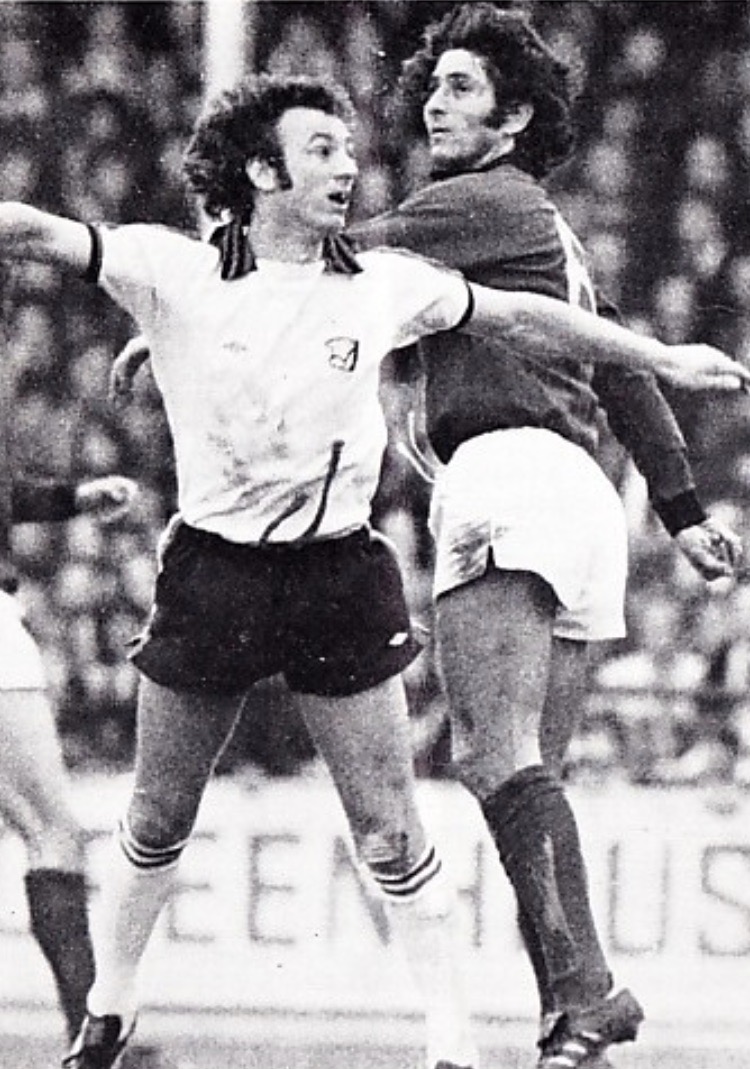

Mellor’s left-foot volley (above) in the 69th minute proved to be the only goal of the game in front of a 26,123 Goldstone Ground crowd. It was the first time in ten seasons that Albion had started with a win.

Mellor later admitted: “Palace were running all over us. It was remarkable that they weren’t about three goals up. Then in the second-half I got the ball some 35 yards out, went on a run, beat a couple of players and scored probably the most memorable goal of my life.”

A frustrated Allison said: “I remember Spider when I was at Manchester City.

“I didn’t want to see him leave for Norwich. Directors force you to do that sort of thing, then they sack you. Spider was a late developer, but his timing is so good now.”

Allison had played a big part in Mellor’s early development and when City chairman Peter Swales’ sold the youngster for £65,000 to Norwich City to bring in some money, he did it behind the manager’s back (he was ill in hospital at the time) and Allison quit Maine Road in protest.

Interviewed in Goal! magazine in June 1973, Mellor said: “It was a wrench leaving the Manchester area. After all, I’d lived all my life within a few miles of City’s ground, and I would never have left Maine Road if things had been left to me, even though I hadn’t nailed down a regular first team place.

“But when I was asked if I would have a chat with Ron Saunders about moving to Norwich, I was ready to go anywhere. After all, if someone tells you that they are prepared to let you go, you know that you are expendable.”

Thirty years later, in an interview with football writer Gary James, Mellor admitted: “I should never have gone to Norwich. I went from a top five side to a bottom five side overnight and it was such an alien environment.

“Norwich is a nice place, and a good club, but at that time the move was totally the wrong move to make. Because they were struggling there was no confidence. The contrast with City was unbelievable.”

And he said of Allison: “He was the best as a coach and motivator and I learnt so much from him. He could be tough, but you listened because he had already delivered so much by the time I got into the first team.”

Before Allison, Mellor had come under the wing of a trio of notable coaches in City’s backroom: Johnny Hart, Ken Barnes and Dave Ewing. “They were very knowledgeable and men of real quality,” he told James. “They knew what they were talking about and they also cared passionately about the game and the club. They’d all had great careers and as a young player you listened and learned.”

Mellor was certainly dedicated to the cause having been given a second chance by City after being shown the door following a trial when he was 15. City’s chief scout Harry Godwin told Goal! magazine: “You could see something there, a useful left peg for instance, and other things, but there wasn’t much of him and, frankly we felt it best to leave it a while.

“We suggested he went away, found himself a local club but kept in touch with us. He did, with a letter asking for another trial. We open all letters we receive, of course, but you could say this is one we are particularly glad about looking into.”

Mellor explained to the magazine: “After that first City trial I had about four games with the Blackpool B side and about a season with Bury as an amateur. Nothing came of it, though I was playing in a local Manchester Sunday league.

“Then I had a particularly good game and got a few good write-ups in a local paper near Manchester. So, I cut them out and sent them to City asking ‘What about another trial?’ They gave me one.”

He first signed as an amateur (in July 1968) and shortly before signing on as a professional at the relatively late age of 19 in December 1969, City loaned him (and goalkeeper Ron Healey) to Altrincham and he played in a 2-1 win at Buxton in the North West Floodlit League on 15 October 1969.

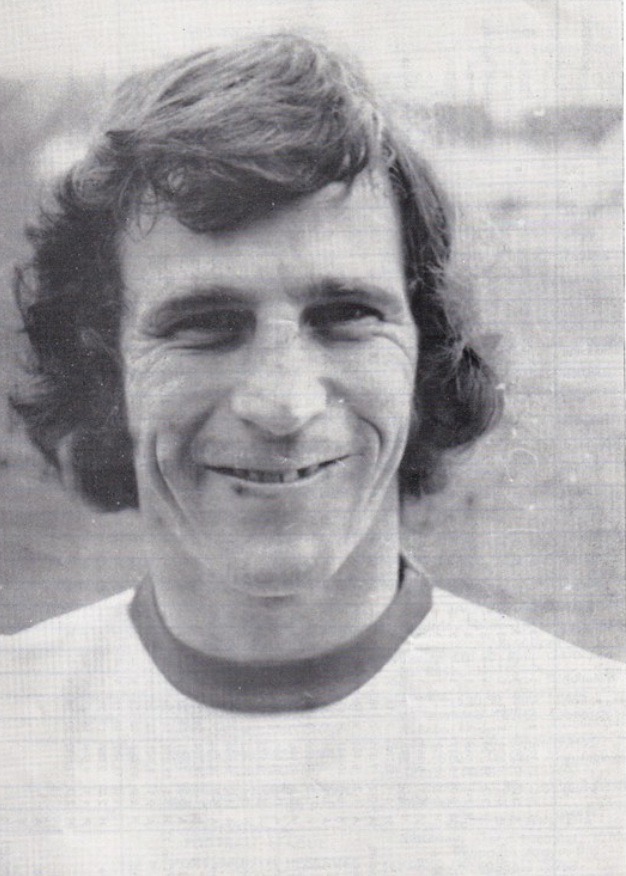

Back at City, he made his reserve team debut in October 1970 away at Aston Villa and six months later stepped up to the first team. It was 20 March 1971 when a nervous Mellor made his City first team debut in a 1-1 draw at home to Coventry City. Ironically, Wilf Smith, the full-back he was up against in the first half of that match, was temporarily a teammate during his first season at Brighton – he had five games on loan to the Albion.

Three years earlier, though, Mellor admitted: “I became a nervous wreck, and in the first half I think that was obvious. I just wasn’t right. Malcolm Allison had a real go at me at half time and warned: ‘If you don’t pull your finger out, you’ll be off!’ So that got me playing! The second half I really worked hard and played my normal game.”

Incidentally, that Coventry side also had Mellor’s future Albion teammate Ernie Machin in midfield alongside Dennis Mortimer, who spent the 1985-86 season with the Seagulls.

Four days after Mellor’s debut, he scored in a European Cup Winners’ Cup quarter-final against Gornik Zabrze, as City won 2-0 (Mike Doyle the other scorer). He was also on target in an end-of-season Manchester derby match when City lost 4-3 to United. “As a City fan, the derby meant an awful lot and scoring your first league goal in a derby is something special, especially for a local lad,” Mellor told Gary James.

It was in the 1971-72 season that Mellor got more of a look-in at first team level, the majority of his 23 starts (plus one as a sub) coming in the first part of the season, before Tony Towers got the nod ahead of him.

In a departure from the pre-season Charity Shield (now Community Shield) norm of League champions playing FA Cup winners at Wembley – Derby and Leeds chose not to be involved – fourth-placed City played Third Division champions Aston Villa 1-0 at Villa Park in August 1972. Mellor might have missed out on a chance to play at Wembley but he was part of history as two subs were allowed for the first time and he went on for Wyn Davies (other sub Derek Jeffries replaced Willie Donachie).

In the season that followed, cut short by his March 1973 sale to the Canaries, he started 13 games and went on as a sub six times. In both seasons he scored four goals.

In all competitions, Mellor made 42 starts for City, plus eight appearances as a sub and scored a total of 10 goals.

In spite of his goalscoring start at Brighton, Mellor was one of several players who didn’t hit it off with Taylor and he was suspended for a fortnight after missing training and returning to Manchester without the manager’s permission.

Perhaps the almost wholesale change in the make-up of the squad was the cause of an indifferent season which saw the side finish uncomfortably close to the relegation places.

Mellor scored six more goals but between the second week of January and the end of the season he only made one start and two sub appearances.

In his end of season summary, John Vinicombe, the Albion reporter for the Evening Argus, said: “Most puzzling aspect of the season was Ian Mellor’s decline.”

The scribe maintained: “There is no satisfactory explanation for what went wrong with Mellor, and his role passed to Gerry Fell, who turned out quite a find considering that he cost only £250 from Long Eaton and had not kicked a ball in the League until the age of 23.”

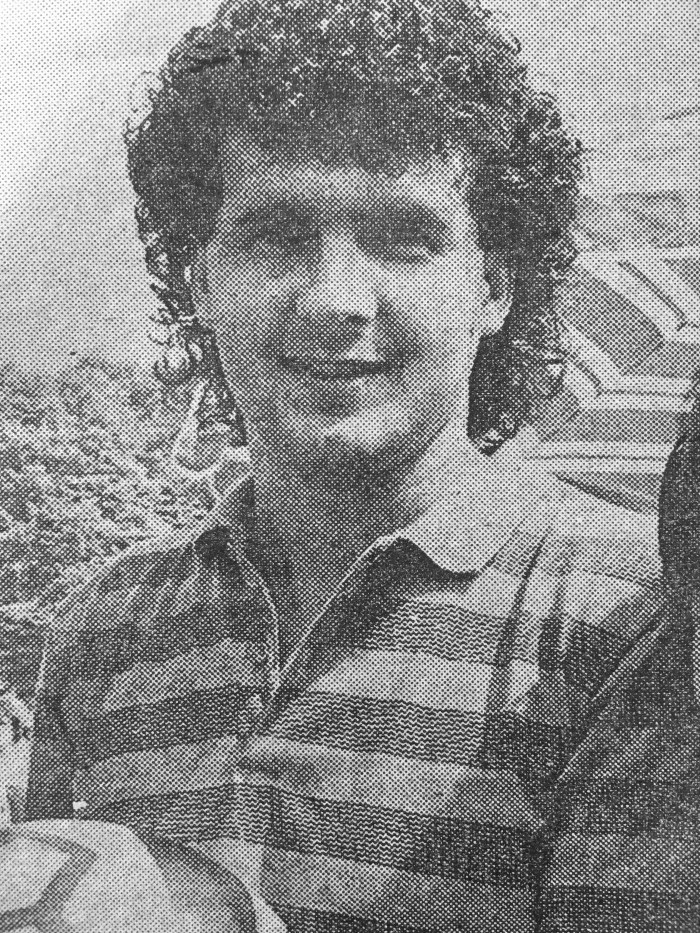

It wasn’t until the end of November of the 1975-76 season that Mellor resumed a regular starting spot in the side but from then on he was almost ever present and notched nine goals in 33 games playing wide on the left as Albion just missed out on promotion.

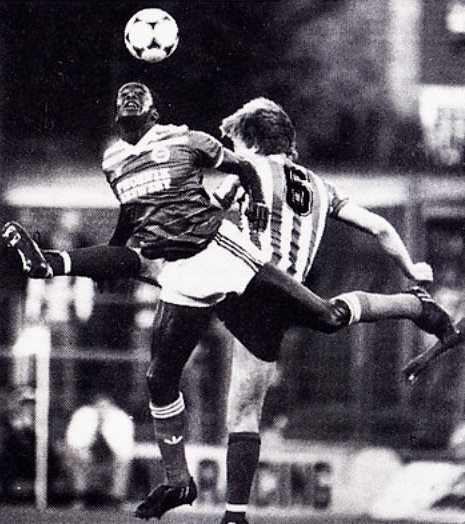

The story of what happened next has been told many times: Alan Mullery saw Mellor as a central striker to play in tandem with the nippy newcomer, Peter Ward, and they swiftly developed a partnership which saw Albion win promotion from the Third Division as runners up behind Mansfield Town.

The aforementioned Vinicombe gave Mellor man-of-the-match as Albion beat Mellor’s future employer Sheffield Wednesday 3-2 to clinch promotion on 3 May 1977 in front of 30,756 fans at the Goldstone.

“The Goldstone fans were so good to us,’ Mellor remembered, “and that year was the happiest in my playing career.”

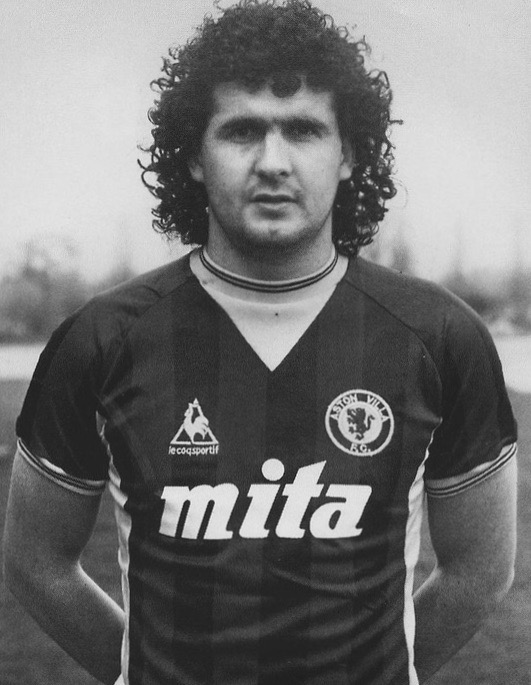

In a similar vein to his retrospective view of regretting leaving City, Mellor also said in hindsight he should have stayed longer with the Seagulls, where he had lost his place to big money signing Teddy Maybank.

“I knew I was better than him, but they had to justify his price and that’s why I got dropped,” Mellor told Spencer Vignes in an Albion matchday programme. “In hindsight, of course, I should have stayed. I was still good enough. I was 29, with two good seasons left in me.”

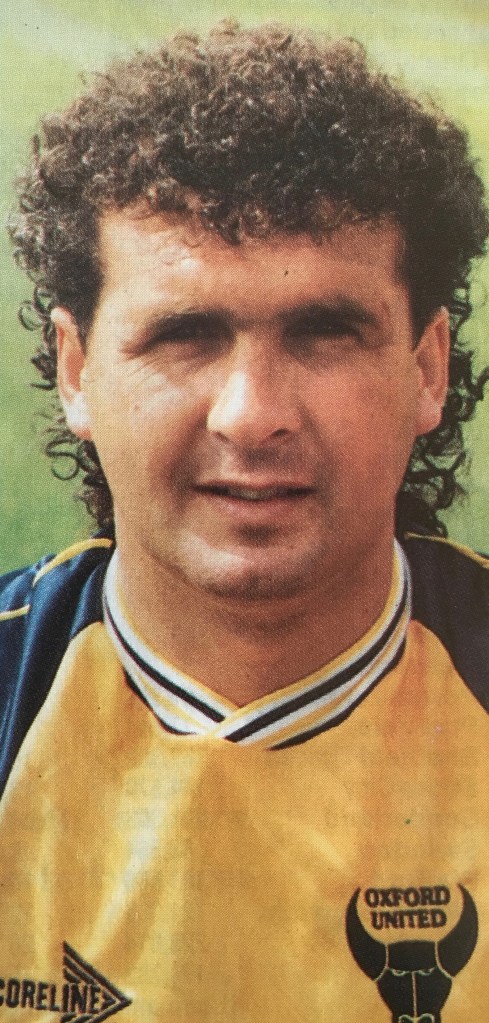

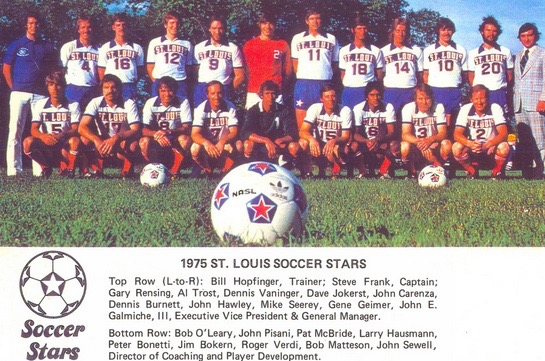

He moved back to his native north west in February 1978 to play for Chester for two years. Their player-manager was former City legend Alan Oakes and his teammates included the aforementioned fellow Charity Shield sub Derek Jeffries and former Albion teammate Jim Walker. Chester FC Memories said of him on Facebook: “His time at the club included scoring in the memorable derby win at Wrexham (2-1) and in the League Cup victory over First Division side Coventry (2-1) early the following season.”

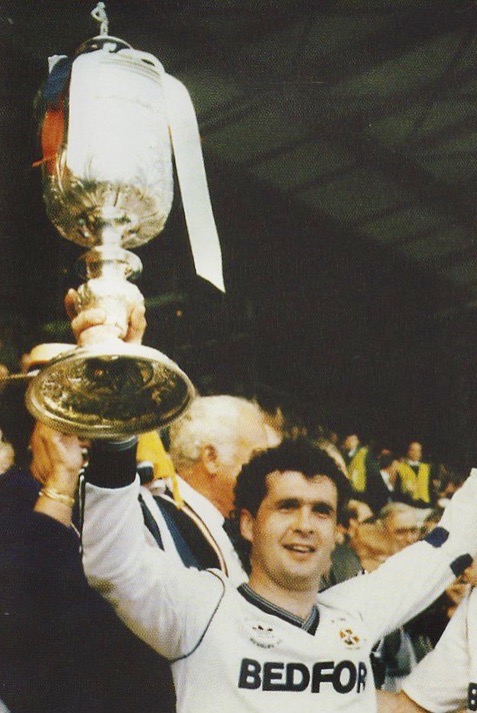

His last Chester goal came in a 2-2 home draw with Sheffield Wednesday who he went on to join under Jack Charlton the following season. Mellor spent three years and scored 11 goals in 79 matches for Wednesday. One of the most memorable was recalled by The Yorkshire Post who reported in 2021: “Mellor made himself a lifelong hero with Wednesdayites midway through his debut season at Hillsborough, when he opened the scoring in the 1979 ‘Boxing Day massacre’ 4-0 home win over neighbours United with a goal from 25 yards. He also hit the woodwork in that game.

“Despite being played in Division Three, the match was watched by over 49,000 fans – a record for third-tier football. The goal is still occasionally sung about to this day.”

Mellor himself told The Sheffield Star: “It’s stange to me, considering it’s 40-plus years ago but it remains such a strong feeling among Wednesday supporters. It’s flattering but crazy!

“You’re only remembered so many years on if you’re a good player and luckily for me I scored a good goal in such an important game.”

Mellor’s final two seasons in league football were spent at Bradford City, managed by former Leeds and England defender Trevor Cherry, and he ended his playing days with Hong Kong club Tsun Wan, Worksop Town, Matlock Town and Gainsborough.

After he had stopped playing, he worked for Puma and Gola, encouraging players to wear their brands of football boots, and he was also a commercial executive for the Professional Footballers Association.

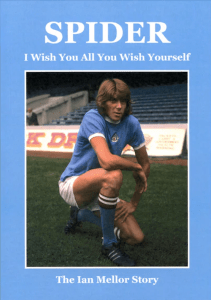

Following his death at St Anne’s Hospice in May 2024, it was announced that his family were to donate proceeds from his autobiography Spider to get a bedroom named in his honour at the charity’s new hospice in Heald Green, Stockport.

His widow Sue said: “It was Ian’s wish that we raise funds for St Ann’s Hospice as a thank you for the wonderful care he received. Ian was proud of his football career and all proceeds from his book will go to charity.”