THE FIRST player ever to be sent off in a Premier League game managed Brighton twice.

Fiery Micky Adams saw red playing for Southampton when he decked England international midfielder Ray Wilkins.

“People asked me why I did it. I said I didn’t like him, but I didn’t really know him,” Adams recalls in his autobiography, My Life in Football (Biteback Publishing, 2017).

It was only the second game of the 1992-93 season and Adams was dismissed as Saints lost 3-1 at Queens Park Rangers.

Adams blamed the fact boss Ian Branfoot had played him in midfield that day, where he was never comfortable.

“He (Wilkins) was probably running rings around me. I turned around and thumped him. I was fined two weeks’ wages and hit with a three-match ban.”

It wasn’t the only time he would have cause not to like Wilkins either. The former Chelsea, Manchester United and England midfielder replaced Adams as boss of Fulham when Mohammed Al-Fayed took over.

His previously harmonious relationship with Ray’s younger brother, Dean, turned frosty too. When Adams first took charge at the Albion, he considered youth team boss Dean “one of my best mates”. But the two fell out when Seagulls chairman Dick Knight decided to bring Adams back to the club in 2008 to replace Wilkins, who’d taken over from Mark McGhee as manager.

“He thought I had stitched him up,” said Adams. “I told him that I wanted him to stay. We talked it through and, at the end of the meeting, we seemed to have agreed on the way forward.

“I thought I’d reassured him enough for him to believe he should stay on. But he declined the invitation. He obviously wasn’t happy and attacked me verbally. I did have to remind him about the hypocrisy of a member of the Wilkins family having a dig at me, particularly when his older brother had taken my first job at Fulham.

“We don’t speak now which is a regret because he was a good mate and one of the few people I felt I could talk to and confide in.”

With the benefit of hindsight, Adams also regretted returning to manage the Seagulls a second time considering his stock among Brighton supporters had been high having led them to promotion from the fourth tier in 2001. The side that won promotion to the second tier in 2002 was also regarded as Adams’ team, even though he had left for Leicester City by the time the Albion went up under Peter Taylor.

Adams first took charge of the Seagulls when home games were still being played at Gillingham’s Priestfield Stadium. Jeff Wood’s short reign was brought to an end after he’d failed to galvanise the side following Brian Horton’s decision to quit to return to the north. Horton took over at Port Vale, where Adams himself would subsequently become manager for two separate stints.

Back in 1999, though, Adams had been at Nottingham Forest before accepting Knight’s offer to take charge of the Albion. He’d originally gone to Nottingham to work as no.2 to Dave Bassett but Ron Atkinson had been brought in to replace Bassett and Adams was switched to reserve team manager.

The Albion job gave him the opportunity to return to front line management, a role he had enjoyed at Fulham and Brentford before regime changes had brought about his departure from both clubs.

On taking the Albion reins, Adams said: “For too long now this club has, for one reason and another, had major problems. The one thing that has remained positive is the faith the supporters have shown in their club.

“The club has to turn around eventually and I want to be the man that helps to turn it around.”

The man who appointed him, Knight, said: “Micky is a formidable character with a proven track record. He knows what it takes to get a club promoted from this division. But, more than that, Micky shares our vision of the future and wants to be part of it. That is why I have offered him a four-year contract and he has agreed to that commitment.”

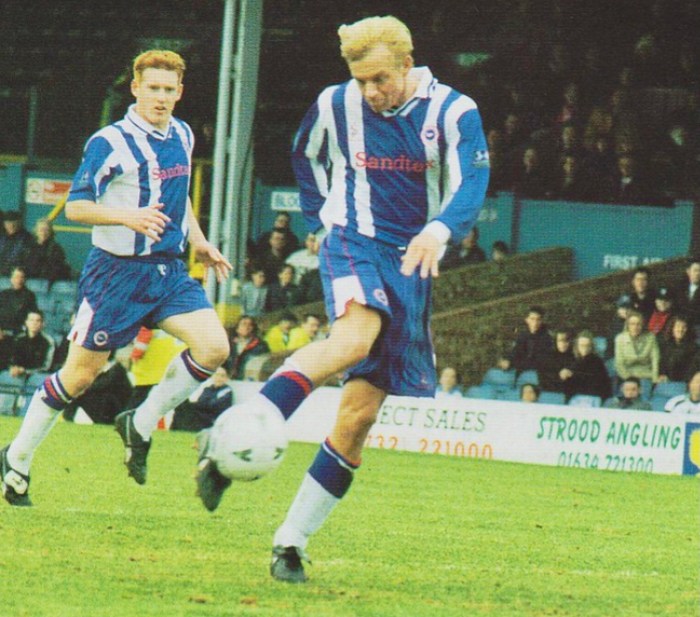

Not long after taking over the Albion hotseat, he was happy to say goodbye to the stadium he’d previously known as home when a Gillingham player in the ‘80s and it was a revamped squad he assembled for the Albion’s return to Brighton, albeit within the confines of the restricted capacity Withdean Stadium.

Darren Freeman and Aidan Newhouse, two players who’d played for Adams at Fulham, scored five of the six goals that buried Mansfield Town in the new season opener at the ‘Theatre of Trees’.

Considering he was only too happy to be photographed supporting the campaign to build the new stadium at Falmer, it’s disappointing to read in his autobiography what he really thought about it.

“My mates and I nicknamed it ‘Falmer – my arse’ although I never said this to Dick’s face,” he said. “There was always so much talk and we never felt like it was going to get done.”

The turning point in his first full season in charge was the arrival of Bobby Zamora on loan from Bristol Rovers. “The first time I saw him he came onto the training ground; he looked like a kid. But he was tall and gangly with a useful left foot; there was potential there.”

Interestingly, considering Adams makes a point of saying he usually ignored directors who tried to get involved on the playing side, he took up Knight’s suggestion that the side should switch to a 4-4-2 formation – and the Albion promptly won 7-1 at Chester with Zamora scoring a hat-trick!

After a so-so first season back in Brighton, not long into the next season Adams was forced to replace his no.2, Alan Cork, with Bob Booker because Cork was offered the manager’s job at Cardiff City, at the time owned by his former Wimbledon chairman, Sam Hammam. Adams reckoned Booker’s appointment was one of the best decisions he ever made.

Surrounded by players who had served him well at Fulham and Brentford, together with the additions of Zamora, Michel Kuipers and Paul Rogers, Adams and Booker steered Albion to promotion as champions. Zamora was player of the season and he and Danny Cullip were named in the PFA divisional XI.

Not long into the new season, the lure of taking over as manager at a Premier League club saw Adams quit Brighton, initially to become Bassett’s no.2 at Leicester City, but with the promise of succeeding him.

“While I thought I had a shot at another promotion, it wasn’t a certainty,” Adams explained. “I knew I had put together a team of winners, and I knew I had a goalscorer in Bobby Zamora, but football’s fickle finger of fate could have disrupted that at any time.”

He admitted in the autobiography: “Had I been in charge at the age of 55, rather than 40, then I perhaps would have taken a different decision.”

While Albion enjoyed promotion under Taylor, what followed at Leicester for Adams was a lot more than he’d bargained for and, to his dismay, he is still associated with the ugly shenanigans surrounding the club’s mid-season trip to La Manga, to which he devotes a whole chapter of his book, aiming to set the record straight.

On the pitch, he experienced relegation and promotion with the Foxes and he doesn’t hold back from lashing out about ‘moaner’ Martin Keown, “one of the worst signings of my career”. Eventually, he’d had enough, and walked away from the club with 18 months left on his contract.

After a break in the Dordogne area of France, staying with at his sister-in-law and her husband’s vineyard, he looked for a way back into the game. He was interviewed for the job of managing MK Dons but was put off by a Brighton-style new-ground-in-the-future scenario. Then Peter Reid, a former Southampton teammate, was sacked by Coventry City. He put his name forward and took charge of a Championship side full of experienced players like Steve Staunton and Tim Sherwood.

The side’s fortunes were further boosted by the arrival of Dennis Wise, but, in an all-too-familiar scenario Adams had encountered elsewhere, the chairman who appointed him (Mike McGinnity) was replaced by Geoffrey Robinson. It wasn’t long before it was obvious the relationship was only going to end one way. As Adams tells it, Robinson was influenced by lifelong Sky Blues fan Richard Keys, the TV presenter, and it was pretty much on his say-so that Adams became an ex-City manager after two years in the job.

With an ex-wife and three children to support as well as his partner Claire, Adams couldn’t afford to be out of work for long and fortunately his next opportunity came courtesy of Geraint Williams, boss of newly promoted Colchester United, who took him on as his no.2.

However, it only got to the turn of the year before he was out of work once again, although, from what he describes, he wasn’t enjoying his time with the U’s anyway because Williams kept him at arm’s length when it came to tactics and team selection.

He was amongst the ranks of the unemployed once again when Albion chairman Knight gave him a call, but, with the benefit of hindsight, he said: “Going back turned out to be one of the biggest mistakes of my life.”

Adams blamed the backdrop of “the power struggle” between Knight and Tony Bloom on the lack of success during his second stint in the hotseat, and he reckons it was Bloom who “demanded my head on a platter”. The fateful meeting with Knight, when a parting of the ways was agreed, famously took place in the Little Chef on the A23 near Hickstead.

Looking back, Adams conceded he bowed to pressure from Knight to make certain signings – namely Jim McNulty, Jason Jarrett and Craig Davies in January 2009 – who didn’t work out. He reflected: “I shouldn’t have taken the job in the first place. I’d let my heart rule my head but, in fairness, I didn’t have any other offers coming through and it seemed like a good idea at the time.

“I wouldn’t ever say he (Knight) let me down, but he had his idea about players. I did listen to him, and maybe that’s where I went wrong.”

He added: “Going back to a club where success had been achieved before felt good, yet, the second time around, the same spark wasn’t there no matter how hard I tried.”

Born in Sheffield on 8 November 1961, Micky was the second son of four children. It might be argued his penchant for lashing out could have stemmed from seeing his father hitting his mother, which he chose to spoke about at his father’s funeral. Adams is obviously not sure if he did the right thing but he felt the record should be straight.

The Adams family were always Blades rather than Wednesdayites and, at 15, young Micky was in the youth set-up at Bramall Lane having made progress with Sunday league side Hackenthorpe Throstles.

While he thought he had done well under youth coach John Short during (former Brighton player) Jimmy Sirrel’s reign as first team manager, Sirrel’s successor, Harry Haslam, replaced Short and, not long afterwards, Adams was released.

However, Short moved to Gillingham and invited the young left winger to join the Gills. Adams linked up with a group of promising youngsters that included Steve Bruce.

In September 1979, he had a call-up to John Cartwright’s England Youth side, going on as a sub in a 1-1 draw with West Germany, and starting on the left wing away to Poland (0-1), Hungary (0-2) and Czechoslovakia (1-2) alongside the likes of Colin Pates, Paul Allen, Gary Mabbutt, Paul Walsh and Terry Gibson.

Adams honed his craft under the tutelage of a tough Northern Irishman Bill ‘Buster’ Collins and began to catch the attention of first team manager Gerry Summers and his assistant Alan Hodgkinson, who had played 675 games in goal for Sheffield United.

He made his debut aged just 17 against Rotherham United but didn’t properly break through until Summers and Hodgkinson were replaced by Keith Peacock (remember him, he was the first ever substitute in English football, in 1965, when he went on for Charlton Athletic against John Napier’s Bolton Wanderers) and Paul Taylor.

“Keith saw me as a full-back and that was probably the turning point of my career,” Adams recalled.

Once Adams and Bruce became regulars for the Gills, scouts from bigger clubs began to circle and at one point it looked like Spurs were about to sign Adams. That was until he came up against the aforementioned Peter Taylor, who was playing on the wing for Orient at the time (having previously played for Crystal Palace, Spurs and England).

“He nutmegged me three times in front of the main stand and, to cut a long story short, that was the end of that. Gillingham never heard from Spurs again,” Adams remembered.

Even so, Adams did get a move to play in the top division when Bobby Gould signed him for Coventry City. Managerial upheaval didn’t help his cause at Highfield Road and when John Sillett preferred Greg Downs at left-back, Adams dropped down a division to sign for Billy Bremner’s Leeds United (pictured below right with the legendary Scot).

“He had such a big influence on my career and life that I wouldn’t have swapped it for the world,” said Adams. But life at Elland Road changed with the arrival of Howard Wilkinson, and Adams found himself carpeted by the new boss after admitting punching physio Alan Sutton for making what an injured Adams considered an unreasonable demand to perform an exercise routine even though he was in plaster at the time.

Nevertheless, Adams admits he learned a great deal in terms of coaching from Wilkinson, especially when an improvement in results came about through repetitive fine-tuning on the training pitch.

“It is the one aspect of coaching that is extremely effective, if delivered properly,” said Adams. “I learnt this from Howard and took this lesson with me throughout my coaching and managerial career.”

However, Adams didn’t fit into Wilkinson’s plans for Leeds and he was transferred to Southampton, managed by former Aston Villa, Saints and Northern Ireland international Chris Nicholl. Adams joined Saints in the same week as Neil ‘Razor’ Ruddock and the pair were quickly summoned by Nicholl to explain the large size of the hotel bills they racked up.

Adams moved his family from Wakefield to Warsash and he went on to enjoy what he reflected on as “the best few years of my playing career”. He was at the club when a young Alan Shearer marked his debut by scoring a hat-trick and the “biggest fish in the pond at the Dell” was Jimmy Case.

Adams described the appointment of Branfoot in place of the sacked Nicholl as a watershed moment in his own career. “Overall he was decent to me and I found his methods good,” he said. And he pointed out: “I was getting older, I’d started my coaching badges and I already had one eye on my future.”

Adams recalled an incident during a two-week residential course at Lilleshall, after he had just completed his coaching badge, when he dislocated his shoulder trying to kick Neil Smillie.

“I was left-back and he was right-wing, and he took the piss out of me for 15 minutes. The fuse came out and I decided to boot him up in the air,” Adams recounted. “The only problem was that I missed. I fell over and managed to dislocate my shoulder hitting the ground. It was the worst pain I’ve ever had.”

If life was sweet at Southampton under Branfoot, that all changed when he was replaced by Alan Ball and the returning Lawrie McMenemy. Adams and other older players were left out of the side. Simon Charlton and Francis Benali were preferred at left-back. Eventually Adams went on a month’s loan to Stoke City, at the time managed by former Saints striker Joe Jordan, assisted by Asa Hartford.

On his return to Southampton, and by then 33, Adams was given a free transfer.

Former boss Branfoot came to his rescue, inviting him to move to League Two Fulham as a player-coach in charge of the reserve team. Branfoot also signed Alan Cork and he and Adams began a longstanding friendship that manifested itself in becoming a management pair at various clubs.

On the pitch, Branfoot struggled to galvanise Fulham and, with the team second from bottom of the league, he was sacked – and Adams replaced him. He kept Fulham up by improving fitness levels and introducing more of a passing game.

But he knew big changes were needed if they were going to improve and he gave free transfers to 17 players, despite clashing with Jimmy Hill, who had different ideas.

An admirer of what Tony Pulis was doing at Gillingham, Adams signed three of their players: Paul Watson, Richard Carpenter and Darren Freeman. He also got in goalkeeper Mark Walton and centre back Danny Cullip. Simon Morgan was one of the few who wasn’t let go, and Paul Brooker emerged as a skilful winger. All would later play under him at Brighton.

Promotion was secured and Adams was named divisional Manager of the Year but after all the celebrations had died down Mohamed Al-Fayed bought the club and things changed dramatically.

“The club was in a state of flux as it tried desperately to come to terms with its new status as a billionaire’s plaything,” Adams acerbically observed. “From having nothing, we had everything.”

Before too long, in spite of being given a new five-year contract, Adams was out of the Craven Cottage door, replaced by Wilkins and Kevin Keegan.

But he wasn’t out of work for long because Branfoot’s former deputy, Len Walker, introduced him to the chairman of Swansea City, who were on the brink of relieving Jan Molby of his duties as manager.

Various promises were made regarding funds that would be made available to him but when they were not forthcoming he realised something was not right and he quit, leaving Cork, the deputy he’d taken with him, to take over.

By his own admission, if he hadn’t been sitting on the £140,000 pay-off he’d received from Fulham, he probably would have stayed. As it was, he was out of work once again…..until he had a ‘phone call from David Webb, the former Chelsea and Southampton defender who was the owner of Brentford, but in the process of trying to sell the club.

His brief was to keep the side in the league and to make it attractive to potential purchasers. It was at Griffin Park that he first met up with the aforementioned Bob Booker, who was managing the under 18s at the time. “He is one of the most loyal and trustworthy friends I have ever known,” said Adams. “He would do anything for you.”

However, although he signed the likes of Cullip and Watson from Fulham, he wasn’t able to stop the Bees from being relegated. During the close season, former Palace chairman Ron Noades bought the club and announced he was also taking over as manager.

Once again, Adams was out of a job but his next step saw him appointed as no.2 to Dave Bassett at Nottingham Forest.

Which brings us almost full circle in the Adams career story, but not quite.

After the debacle of his second stint in charge of Brighton, he was twice manager at Port Vale, each spell straddling what turned out to be a disastrous period in charge of his family’s favourite club, Sheffield United.

It was Adams who gave a league debut to Harry Maguire during his time at Bramall Lane, but the side were relegated from the Championship on his watch, and he was sacked.

Adams took charge of 249 games as Vale boss but quit after a run of six defeats saying he’d fallen out of love with the game.

It didn’t prevent him having another go at it, though. He went to bottom of the league Tranmere Rovers and admitted in his book: “It was arrogance to think I could turn round a club that had been relegated twice in two seasons.”

In short, he couldn’t and he ended up leaving two games before the end of what was their third successive relegation.

“It was a really poor end to a career that had started so promisingly at Fulham,” he said.

He made 14 appearances for them before being snapped up for £40,000 by Tottenham Hotspur in 1974 and made his first team debut for Spurs while still only 16. A former teammate at that time, Andy Keeley said in

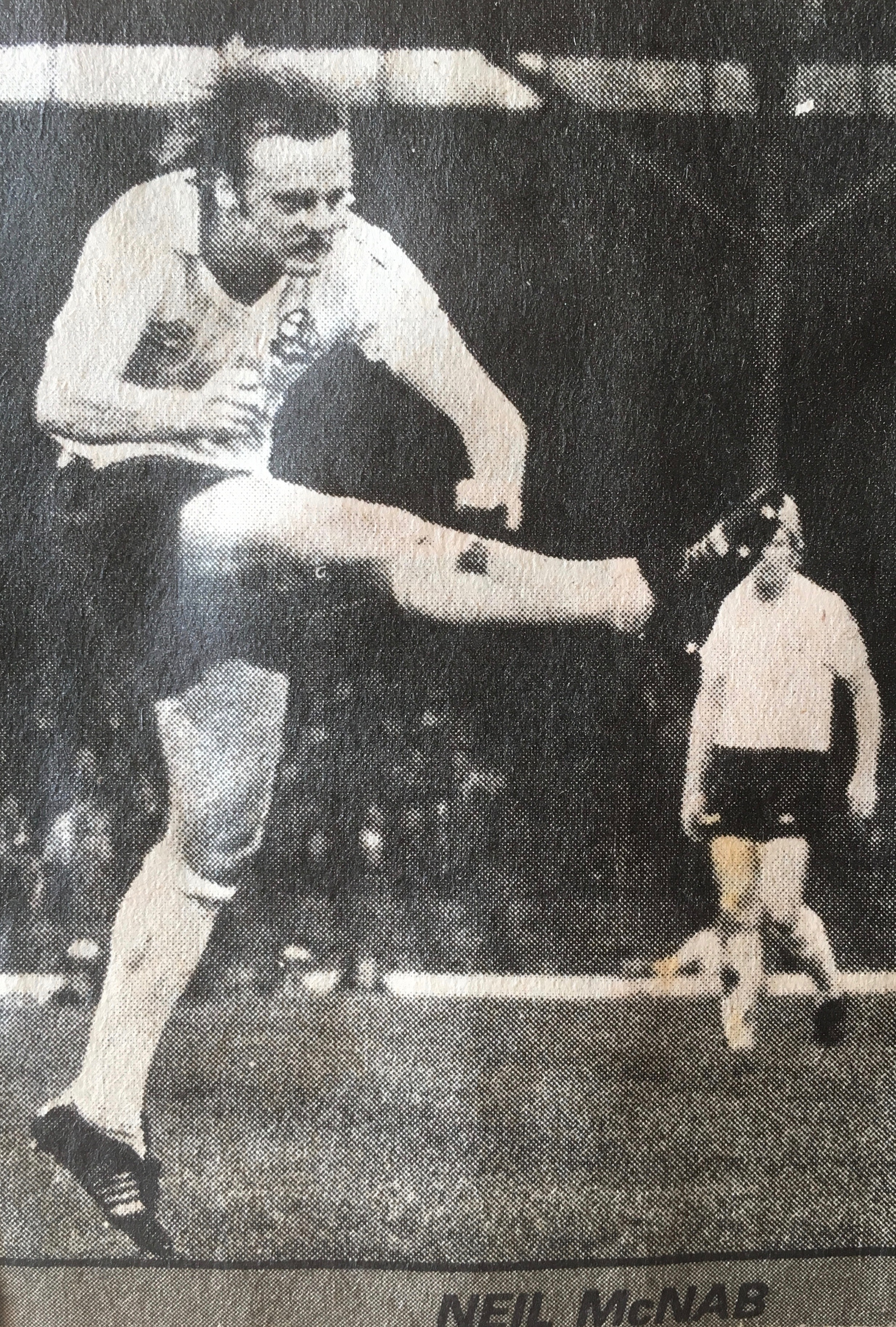

He made 14 appearances for them before being snapped up for £40,000 by Tottenham Hotspur in 1974 and made his first team debut for Spurs while still only 16. A former teammate at that time, Andy Keeley said in  In November 1978, Bolton Wanderers paid £250,000 for him but after only 35 appearances for the Trotters, in February 1980, Mullery signed him for Brighton.

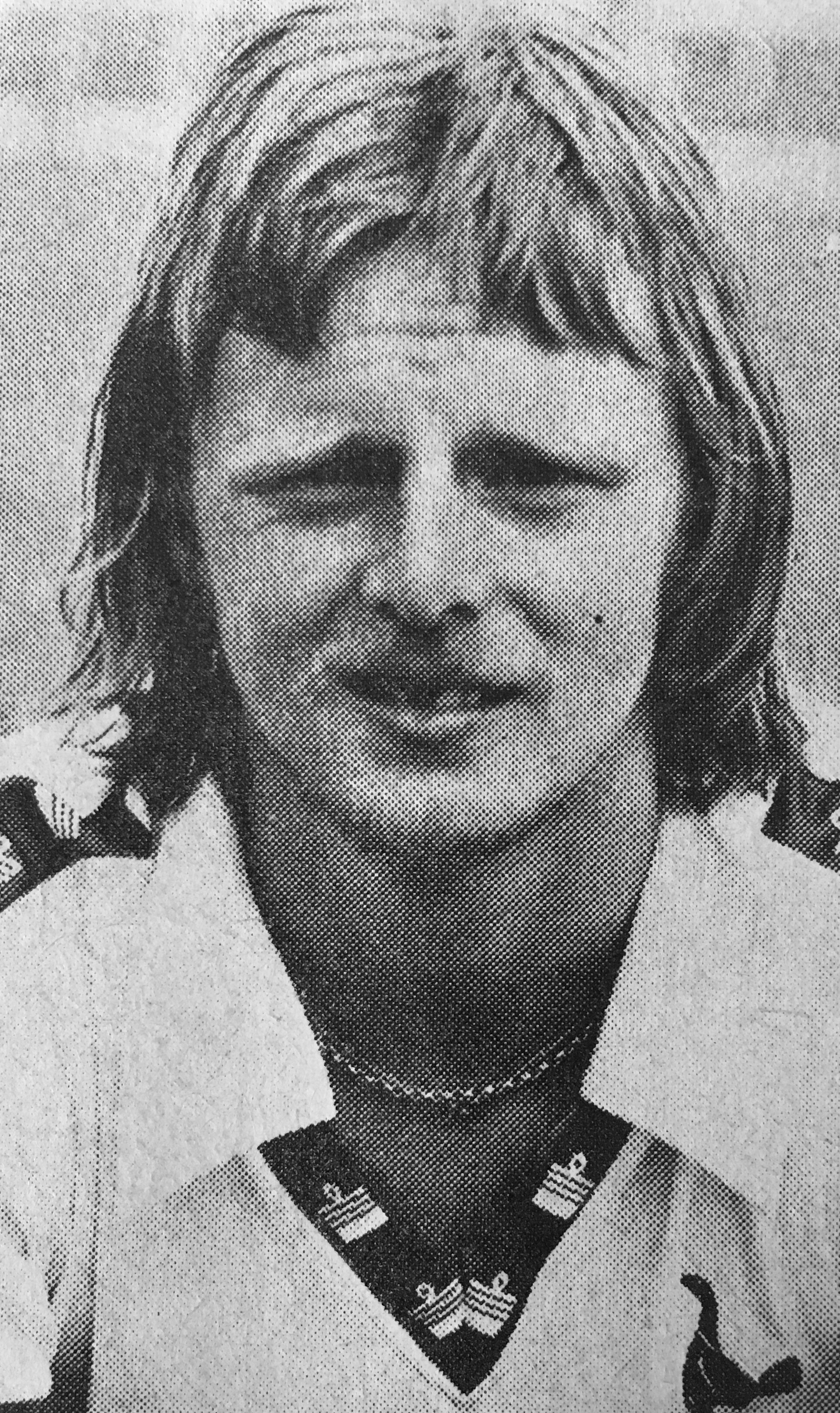

In November 1978, Bolton Wanderers paid £250,000 for him but after only 35 appearances for the Trotters, in February 1980, Mullery signed him for Brighton. Acknowledging his initial signing failed to excite the City faithful, it added: “McNab developed into a skilful, combative midfielder who became a huge crowd favourite. Not unlike Asa Hartford (pictured above with McNab), McNab was a schemer who could pick a pass and kept the team’s tempo ticking over.”

Acknowledging his initial signing failed to excite the City faithful, it added: “McNab developed into a skilful, combative midfielder who became a huge crowd favourite. Not unlike Asa Hartford (pictured above with McNab), McNab was a schemer who could pick a pass and kept the team’s tempo ticking over.”