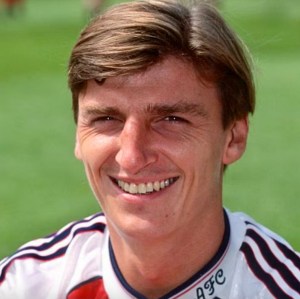

ONE-TIME Arsenal back-up defender Colin Pates had a Gunners legend to thank for persuading him to quit the game before he did any life-altering damage.

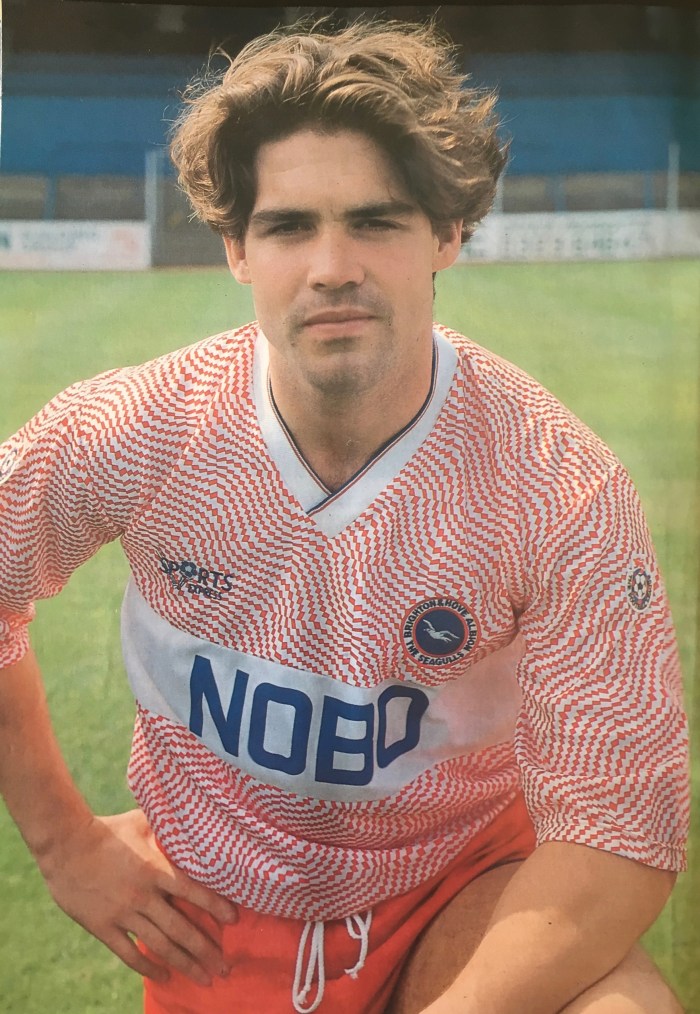

Thankfully, Pates took Liam Brady’s advice to bring his professional playing days to an end at Brighton in January 1995 and he went on to have a long and successful career coaching at an independent school in Croydon where he introduced football to what was previously a rugby-only establishment.

“Liam told me that I should think of my health before my playing career and that I would be a fool to myself if I carried on playing,” Pates told the Argus in a 2001 interview.

“My knee had fallen apart and it was the right advice. If I’d ignored it, I could well have ended up not being able to walk.

“Footballers need to be told when it is the end. I’ll always be grateful to Liam for that.”

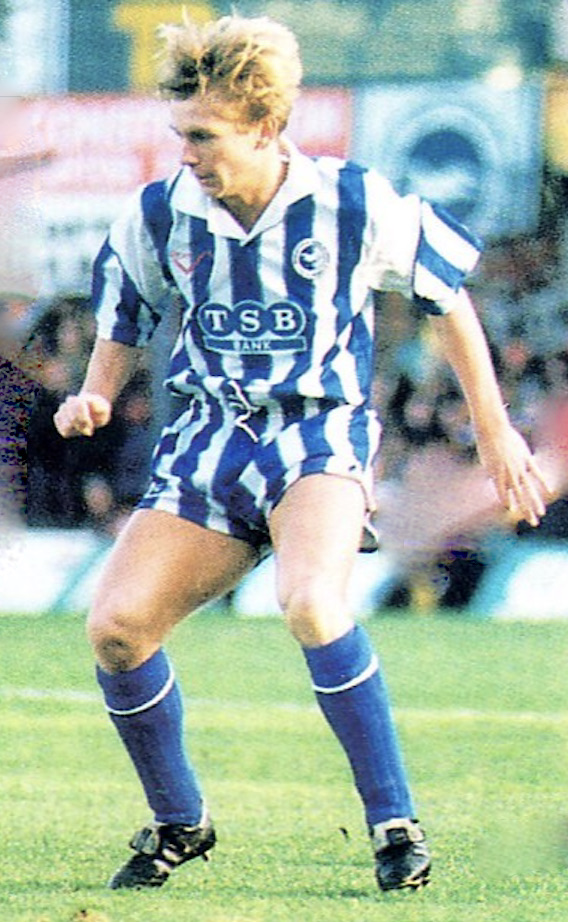

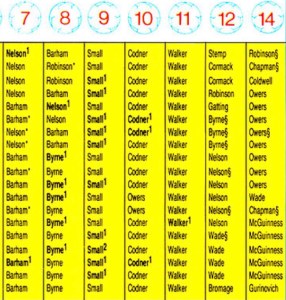

Pates had played the last of 61 games in the stripes (a 0-0 home draw against Bournemouth) only six weeks after he was presented with a silver salver by former England manager Ron Greenwood to mark his 400th league appearance (on 24 September 1994, a 2-0 home win over Cambridge United).

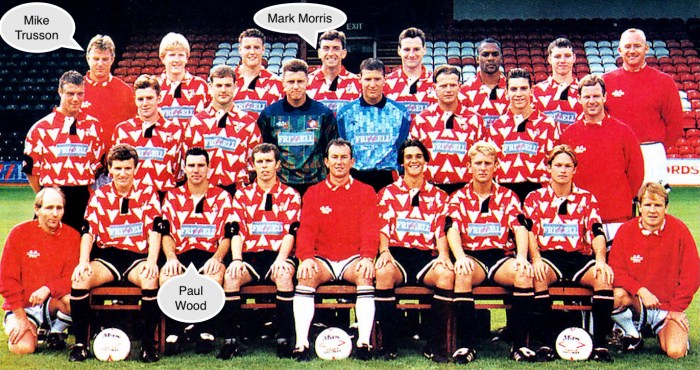

In the matchday programme of 17 December, Brady confirmed that Pates and fellow defender Nicky Bissett, (who’d twice broken a leg and then sustained a knee injury) would be ruled out for the rest of the season. Neither played another game for the Seagulls.

It brought to an end Pates’ second spell with the Seagulls, having originally spent a most productive three months on loan in 1991 helping to propel the club to a Wembley play-off final. If Albion had beaten Notts County that May, Pates may well have made a permanent move to the south coast. As it was, he said: “Unfortunately, the club couldn’t meet Arsenal’s asking price for me that summer so I returned to Highbury.

“But when my contract expired in 1993, there was only one club I wanted to be at… Brighton.”

As if Tony Adams, Andy Linighan, David O’Leary and Steve Bould weren’t enough centre back competition at Arsenal, manager George Graham had also taken Martin Keown back to the club from Everton for £2m – six and a half years after selling him to Aston Villa for a tenth of that amount.

So, it was no surprise that Pates found himself surplus to requirements at Highbury and given a free transfer. Graham’s old Chelsea teammate, Barry Lloyd, eagerly snapped up the defender for a second time, this time on a permanent basis.

Goalkeeper Nicky Rust, still a month short of his 19th birthday, who’d also been given a free transfer by Arsenal, made his Albion league debut in the season-opener at Bradford City behind the returning Pates, who had just celebrated his 32nd birthday four days before the game.

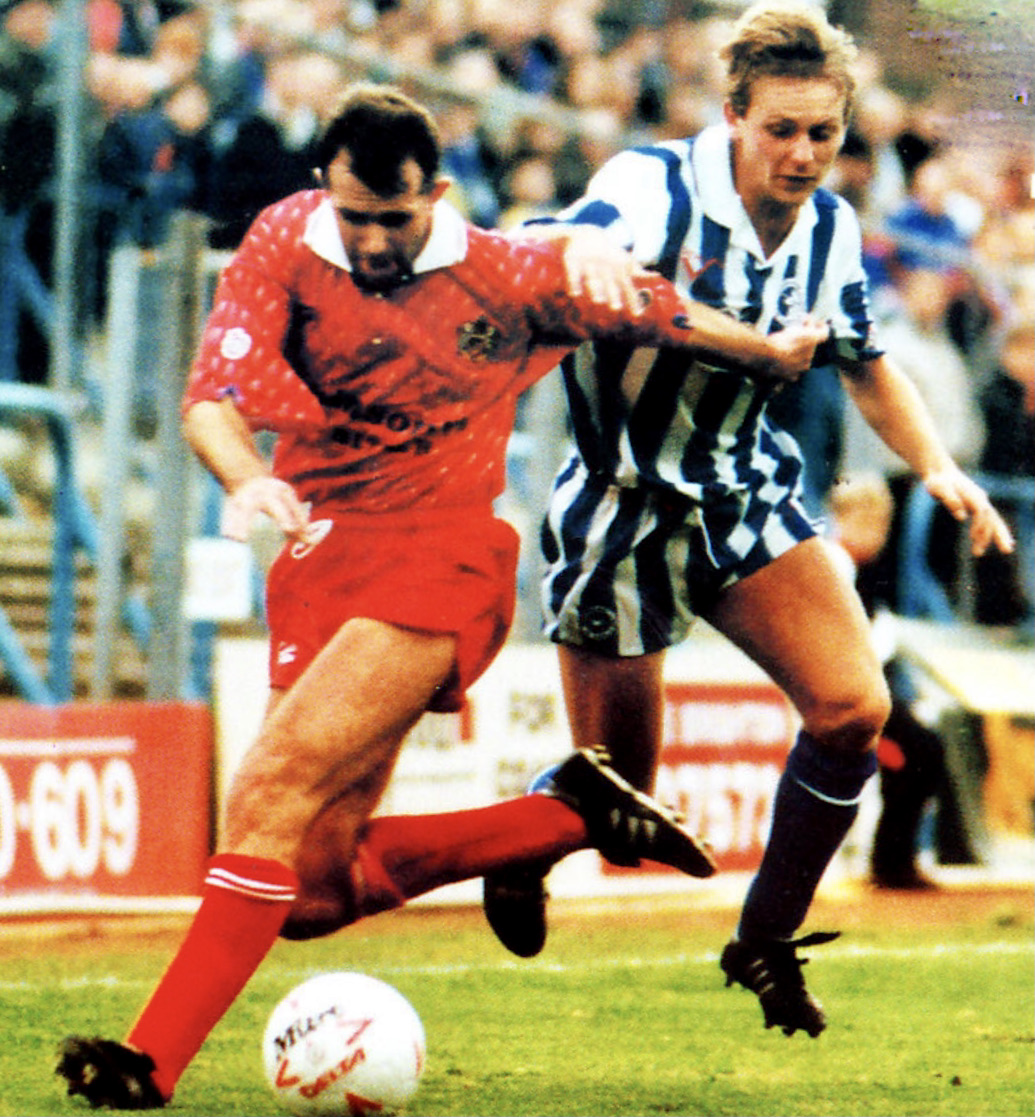

After starting the first 10 matches alongside the aforementioned Bissett, Pates suffered an abductor muscle injury early on in a 5-0 drubbing away to Middlesbrough in the League Cup which necessitated a spell on the sidelines. He missed nine matches – only one of which was won.

These were the dying days of the seven-year Lloyd era and, even with Pates back in the side, one win, two draws and four defeats brought the sack for the manager.

Any doubts new manager Brady had about Steve Foster and Pates were swiftly dispelled, as he wrote about in his autobiography (Liam Brady: Born To Be A Footballer).

“Fossie was 36. I feared he might be going through the motions at this stage in his career and it would have been hard to blame him,” said Brady. “Colin Pates was a few years younger, but he’d been at Chelsea and Arsenal and could have been winding down.

“I appealed to them to give me a dig out, to lead this rescue mission. And they responded just as I hoped.”

Together with the even older Jimmy Case, who was brought back to the club from non-league Sittingbourne, they “brought on” the younger players in the new man’s first few weeks and months.

Under Brady, young Irish centre-back Paul McCarthy played alongside Foster in the middle, with Pates at left-back. And Pates saw the arrival of some familiar faces in the shape of young Arsenal loanees, first Mark Flatts and then Paul Dickov, whose successful spells helped Brady to steer the Seagulls to safety by the end of the season.

“I really enjoyed it, playing mainly at left-back,” said Pates. “It was a great family club and I made a lot of friends there along the way.”

At the time Pates had to call it a day, Albion were a third-tier side but the bulk of his career had been played at the top of the English game for two of its leading lights in Chelsea and Arsenal, and briefly Charlton Athletic.

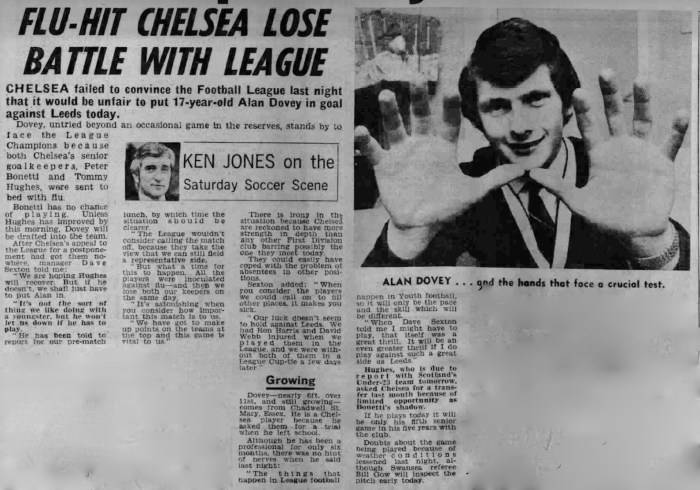

The player’s move to Arsenal from Charlton for £500,000 in January 1990 raised more than a few eyebrows because he was 28 at the time and none of Arsenal’s back four – Lee Dixon, Bould, Adams and Nigel Winterburn – looked like giving way.

“People asked me why I went there,” said Pates. “But when a club is paying that money and that club is Arsenal who wouldn’t go and take the chance?

“I knew this was going to be the last opportunity to have a move like this in my career and although I knew I was only being signed as cover, I couldn’t turn it down.”

He continued: “I’d joined a team that had just won the league, that would do so again in 1990-91 and they had the fabled back four – the best defensive unit in world football at the time.”

The website upthearsenal.com acknowledged: “Pates had built a solid reputation at Chelsea as a dependable defender who was strong in the air and no slouch on the deck.”

Pates added: “When I first met George (Graham) in his office at Highbury, he was honest and straight talking. He told me I’d have to work hard to get into the side.”

However, within a month he made his Gunners debut at left back in place of the injured Nigel Winterburn in a 1-0 defeat to Sheffield Wednesday. It turned out to be his only first team appearance that season.

Although he found it difficult to motivate himself for reserve team football, he pointed out: “I still enjoyed the training sessions with the first team and I did learn a lot about defending from George, even at that late stage in my career.”

However, after his return from the loan spell at Brighton, he saw action as a sub in three pre-season friendlies ahead of the 1991-92 season and that autumn had his best run of games in the first team.

He featured in eight games on the trot between October and November 1991 and memorably scored his one and only goal for Arsenal in a European Cup match at Highbury against a Benfica side managed by Sven-Göran Eriksson. He also played in the February 1992 1-1 North London derby against Spurs and made two appearances off the bench that season.

It was a similar story in the 1992-93 campaign when he went off the bench on five occasions although he had two starts: in a 2-0 win at Anfield (Anders Limpar and Ian Wright the scorers) and a 3-2 defeat away to Wimbledon.

“I was a bit-part player but it was a good time to be at the club with the cup finals and being part of the squads,” said Pates.

On his release from Brighton, Pates had a spell as player-manager of Crawley, played a handful of games for non-league Romford, and coached youngsters in various places including Mumbai in India and the Arsenal School of Excellence.

Pates told The Guardian in a 2002 interview how a sense of history and continuity was the first thing he had noticed when he signed for Arsenal.

Brady, Paul Davis, Bould and other former Arsenal players were all invited to the Arsenal academy, and Pates told the newspaper. “Young players need people like Stevie Bould to tell them how proud they should be to pull the shirt on and to show them what’s expected of them. “When I joined Arsenal, everyone was kind and considerate. You were left in no doubt about how you were supposed to conduct yourself. For the way it’s run, it’s the best club in the country.”

By then though, Pates had begun a new career as a coach getting football off the ground at the independent Whitgift School in Croydon. He was to stay 24 years at the school having been invited to introduce football by its headmaster, Dr Christopher Barnett.

The story has been told in depth in several places, notably in London blog greatwen.com by Peter Watts, among others. Watts wrote: “A posh school in the suburbs is not where you’d expect to find a hard-bitten former pro, and Pates admits: ‘Whitgift is quite alien to some of us, because we had state school educations. It was intimidating, and not just for the boys.’ But he jumped at the opportunity.

At first, he took a sixth-form team on Wednesday afternoons, but there were no goalposts, pitches, teams or even footballs! “We didn’t have anything. So, we had to start from scratch, pretty much teach them the rules,” he said.

“They were rugby boys playing football, so these were quite aggressive games. But after three years we introduced fixtures and we’ve never looked back,” said Pates.

In an interview with the Argus in October 2001, Pates added: “We went over the local common for our first training session with some under-18s after finding a ball that looked like the dog had chewed it up.

“I had to go right back to basics. All they had known was rugby, so it was a case of going through the rules of football to start with, like the ball we use is round!

“I was told that in 300 years football had never been considered. But a lot of the boys and their parents expressed an interest.

“It might be an independent school but you can forget the black and white filmed images of public school kids. Most are from working class backgrounds and they love their football.

“It grew a lot quicker than the head thought and he told me I should take over as master in charge of football.”

As the sport grew, he recruited his former Charlton teammate (and ex-Brighton, Wolves and Palace full-back) John Humphrey and Steve Kember, the former Chelsea and Palace midfielder to help with the coaching.

Asked about it on the chelseafancast.com podcast Pates delighted in recounting how from time to time he would show Humphrey a video clip of a rare goal he scored for Chelsea against Wolves when he flicked the ball over Humphrey’s head in the build-up to it – however Chelsea lost that 1983 match 2-1!

More seriously, Pates spoke at length to Watts about the benefits of a good education in case things didn’t pan out.

“You have to be an exceptional footballer to make it these days. So, we want to give them the best opportunity to be a footballer, but also give them a magnificent education so if they don’t sign scholarship forms they have something to fall back on. It works for us, it works for the academies and it works for the families.”