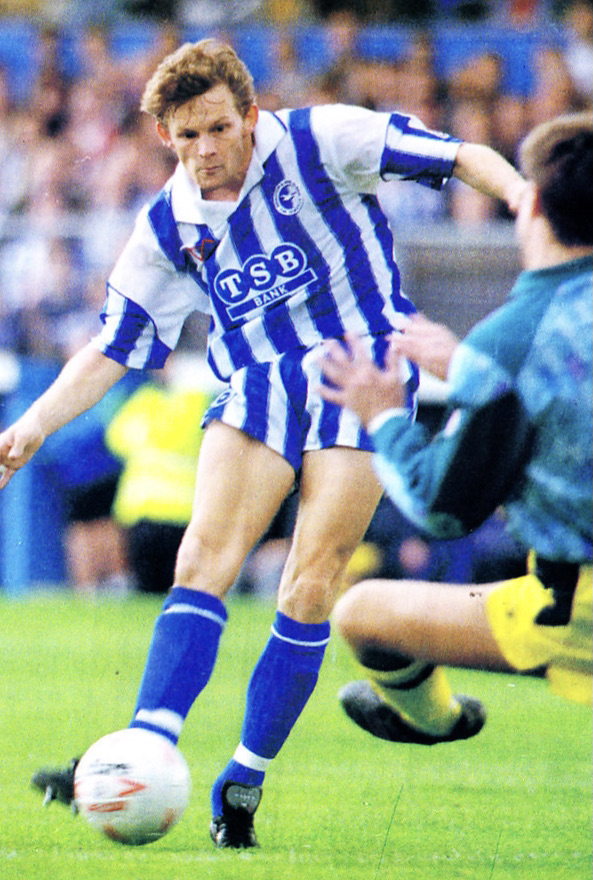

STEVE COTTERILL, who made a lasting connection with Brighton fans after impressing during an all-too-brief spell in 1992, saw his injury-plagued playing career come to a juddering halt at Bournemouth.

Cotterill today is back where it all began managing his hometown club, Cheltenham Town, but back in the day he was an old school bustling centre forward who began to get his career back on track with Barry Lloyd’s cash-strapped Seagulls.

The West Country striker, affectionately nicknamed Wurzel (after TV character Wurzel Gummidge) by Albion veteran Steve Foster (back with the club he left in 1984) because of the distinctive Gloucestershire burr when he spoke, was desperate to get back playing regular league football after spending 14 months sidelined with an anterior cruciate ligament injury to his knee while playing for Wimbledon, who were just about to compete in the inaugural season of the Premier League.

“When Brighton asked for me on loan, I desperately wanted the chance to show what I could do,” he said. “I think that Martin Hinshelwood (Lloyd’s deputy) was impressed when he saw me a couple of years ago in a tournament at Arundel.”

Wimbledon didn’t tend to loan players out but manager Joe Kinnear, a former Brighton player himself back in the 1970s, agreed for Cotterill to make the move to try to regain his fitness.

Lloyd was managing on a shoestring after Albion had been relegated back to the third tier having missed out on leaving the second tier in the opposite direction the year before when losing the play-off final at Wembley to Neil Warnock’s Notts County.

He’d been forced to sell the prolific striking duo of Mike Small, to West Ham, and John Byrne, to Sunderland, and their replacements had been a huge disappointment.

Mark Gall, signed from Maidstone, offered a glimmer of hope, but one-time Arsenal striker Raphael Meade and former Everton trainee Mark Farrington failed to convince.

As the 1992-93 season got under way, Gall was unavailable due to a knee injury that eventually forced him to retire, Meade had departed and questions continued over Farrington, so Lloyd opened the season with loan signings Cotterill and Paul Moulden (who’d been at Bournemouth for seven months after leaving Manchester City) from Oldham Athletic (also in the Premier League that season), where he was surplus to requirements.

Each were on the scoresheet in Albion’s opening day 3-2 defeat at Leyton Orient and Cotterill scored again in a home 2-1 win over Bolton Wanderers and an away 3-2 win at Exeter City.

It looked like Lloyd had cracked it as the pair combined well and also enjoyed their partnership, as Moulden told Brian Owen in an interview with the Argus in October 2016. “One of the reasons I loved playing for Brighton was Mr Banter himself, Steve Cotterill. We met up like we had never been apart. I’d start the banter and he’d finish it or vice versa.

“We destroyed many a centre-half partnership during that three months. I was gutted to leave. I mean that very sincerely – absolutely gutted. I couldn’t believe nobody would have bought me and Steve as a pairing.

“We were both out of favour with our clubs and we hit it off so well. But it wasn’t to be – at Brighton or at any club.”

Cotterill had certainly hinted at making the move more permanent, saying in a programme interview: “I am glad to be playing again and scoring the odd goal. Who knows what may happen from here?”

He signed off by scoring the only goal of the game that beat Wigan Athletic at the Goldstone.

Unfortunately, parent club Wimbledon, playing in the inaugural season of the Premier League, wanted the sort of fee for Cotterill that, at the time, Albion couldn’t afford.

He’d scored four times in 11 matches – and on his return to the Dons promptly scored both of their goals in a 2-2 draw away to Southampton. But with John Fashanu and Dean Holdsworth ahead of him, he managed just a handful of games for the Dons.

He did get a start ahead of Holdsworth at home to Liverpool in January 1993 and scored the Dons second goal (Fashanu scored a penalty in the first half) as the Reds were put to the sword 2-0 at Selhurst Park (where Wimbledon played home games at the time).

Cotterill added to his Dons goal tally the following month, in the second minute of added on time in a fifth round FA Cup tie at Spurs, but it was simply a consolation as the home side ran out 3-2 winners. Cotterill had replaced Roger Joseph for the second half.

In the summer of 1993, Bournemouth found the £80,000 that Wimbledon wanted for Cotterill and he signed for the Cherries under manager Tony Pulis.

Pulis paired Cotterill with Steve Fletcher, who eventually went on to become a Cherries legend after a slow start. Fletcher spoke highly of his former teammate when interviewed by Neil Perrett for the Bournemouth Echo in March 2010.

In their first season together, their fortunes were quite contrasting. Cotterill scored 14 goals and was crowned supporters’ Player of the Year while Fletcher endured a second barren year following a £30,000 move from Hartlepool.

“Steve took me under his wing,” recalled Fletcher. “My first couple of years were hard. I started playing alongside Efan Ekoku and was a lone striker after he had been sold.

“I was young and needed someone to come in and help me out. Steve had experience of playing at a higher level with Wimbledon and was happy to pass it on.

“He used to sit me down and we would talk through things. He would back me up in the paper and I remember him jumping to my defence when someone criticised me at a fans’ forum.

“Things like that stick in your mind. I had moved down from Hartlepool and it was tough. Steve really looked after me during those early years and it is something I’ve always appreciated. I’ve kept in touch ever since.”

It was during their second season together that their fortunes reversed. Cotterill’s career was prematurely cut short following a serious knee injury sustained against Chester City in September 1994, with only 10 games of the season played. Fletcher went on to be crowned Player of the Year.

Cotterill said: “I had a good time at Bournemouth, but unfortunately my lasting memory was my last game.

“Snapping my cruciate ligament was the thing I remember because it was the last thing I did and it’s the thing that lives with me. I still remember doing it and it’s a bad memory really, but I did have some good times there and it’s a great part of the world.”

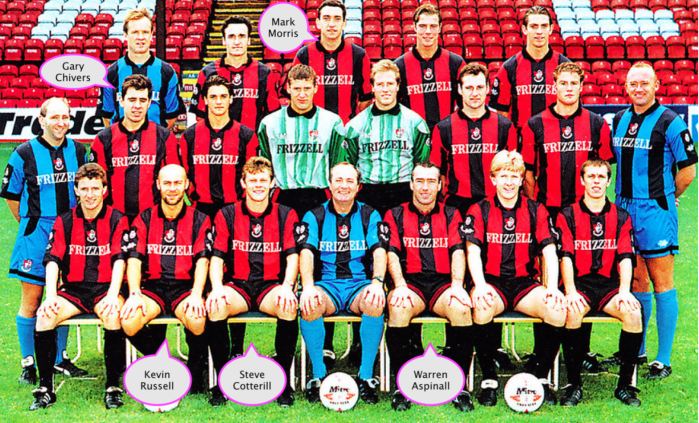

Pulis was succeeded by former player Mel Machin and in that campaign’s team photo there were two teammates who had played for Brighton in Gary Chivers and Kevin ‘Rooster’ Russell and two who would do so in the future: Mark Morris and Warren Aspinall.

Cotterill recalled in a 2023 interview with gloucestershirelive.co.uk: “I know Rooster very well. I played with him at Bournemouth and he’s a great guy and a good coach.

“I liked him when I played with him because he used to stick crosses on a sixpence for me. I remember scoring a few goals from his crosses.”

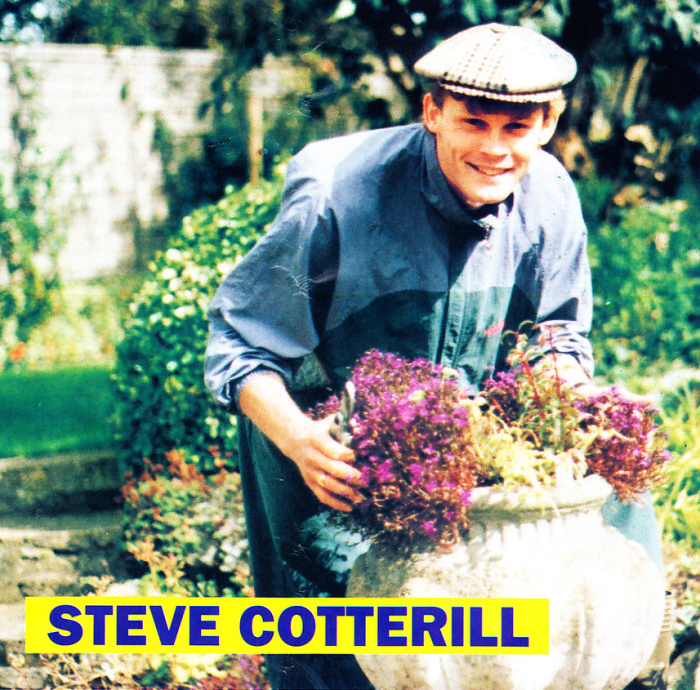

Born in Cheltenham on 20 July 1964, Cotterill’s first football was played at primary school but his secondary school years were spent at rugby-playing Arle Comprehensive so it was a relief to resume the game he loved for the then semi-professional Cheltenham Town youth team.

He progressed to the reserves and first team of what at the time was a Southern League Premier Division club before his friend Tim Harris, assistant manager at Alvechurch, persuaded him to switch clubs, while he was working full time for a builder’s merchant.

“I must have impressed there because they cashed in and sold me for £4,000 to Burton Albion,” he recalled in a matchday programme interview.

His progress for the side who a dozen years earlier had unearthed the talent of Peter Ward saw him net 44 goals in 74 games for the Brewers between 1987 and 1989

“I have a great affection for Burton Albion and for all those people that work there and I’ll never forget my time there,” he said in a 2018 interview after his Birmingham side played his old club in the FA Cup.

Such a prolific scoring rate caught the eye of Bobby Gould, whose Wimbledon side were punching way above their weight in the old First Division, and the previous season had achieved an historic FA Cup win over Liverpool.

Wimbledon reportedly paid more than £100,000 to take him to south London and he recalled: “I scored on my league debut on 29 April 1989 in a 4-0 win against Newcastle and I thought I was on my way.

“But I didn’t get much of a look-in in the following season and then, when Ray Harford took over, I played a few games before I suffered a horrendous knee injury.”

Cotterill was out for 14 months and only managed a couple of reserve games towards the end of the 1991-92 season, before making the temporary move to Brighton.

Interesting to note in an Albion programme interview with him during his loan spell that he ended it by saying: “I want to stay in the game and I’d like to become a coach or manager.”

He certainly did that and what he did in those capacities is a story in itself. His first assignment was in Ireland where he succeeded his former Wimbledon teammate Lawrie Sanchez at League of Ireland’s Sligo Rovers.

But his hometown club Cheltenham Town offered him a management opening back in England in 1997, and he steered them from Southern League football into the Conference and then into the bottom tier of the Football League. He twice won the Manager of the Year title and earned another promotion, to the third tier, via a play-off final victory over Rushden & Diamonds.

After management and coaching posts at 12 clubs in various parts of the country, he returned to Cheltenham after a 23-year absence in September 2025 and was subject of an extensive feature on Sky Sports hailing his messianic return at the age of 61.

In between, he managed Stoke, Burnley, Notts County, Portsmouth, Nottingham Forest, Bristol City, Birmingham, Shrewsbury Town and Forest Green Rovers.

He cut short his tenure at Stoke in the autumn of 2002 after just 13 games to become assistant manager at Sunderland under Howard Wilkinson, but their stay on Wearside was also short lived, the pair being dismissed after only 27 games in March 2003.

Before taking up the Burnley post, Cotterill was briefly a coach under Micky Adams at Leicester and he was twice a coach under Harry Redknapp: at Birmingham, before taking over as manager, then again at QPR for the second half of the 2012-13 season.

Cotterill has certainly been on the wrong end of some trigger-happy club owners over the years but one of the toughest challenges he’s faced during his long career was during his time as boss of League One Shrewsbury during the Covid-19 pandemic. He was twice admitted to Bristol Royal Infirmary, spending time in intensive care, suffering badly from the virus and pneumonia.

Cotterill left the Shrews job in June 2023 and was out of work until January 2024, when he took charge of Forest Green Rovers.

He was unable to stave off relegation from the Football League, but he rebuilt the side during the summer of 2024 to push for promotion back to League Two. When Southend United visited The New Lawn in the National League on 15 March 2025, the 2-2 draw was Cotterill’s 1,000th game as a manager.

Now back at Whaddon Road, he’s steered the Robins clear of the bottom-of-the-league spot they occupied when he returned.

At his first game back, a banner in the stands referenced the return of the king, and Cotterill declared: “I felt the whole of Cheltenham behind me that day. Not that I have not felt it since too, by the way, because they have been incredible ever since I have been back.

“Even when I was at other clubs, this club has always been important to me. It is my hometown.”

Nonetheless, the Albion has always occupied a soft spot, as he once wrote in his programme notes prior to a Cheltenham v Brighton fixture: “I thoroughly enjoyed my time at Brighton and, whenever we’ve gone there, I’ve always had a great reception from their supporters. They’ve been terrific.”

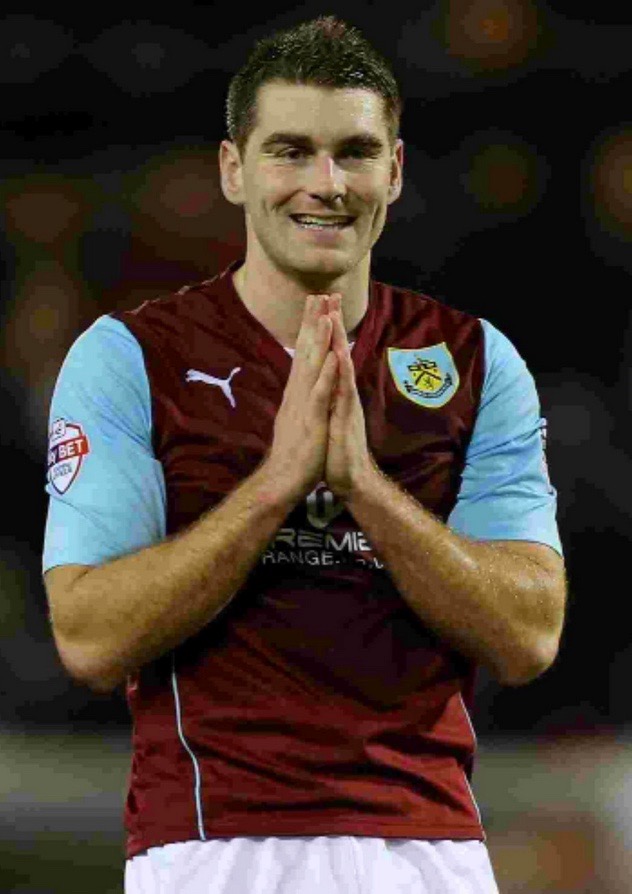

“I don’t want to sit around – I love playing,” said Vokes. “Brighton have a great way of playing football that is different to a lot of teams in the Championship.”

“I don’t want to sit around – I love playing,” said Vokes. “Brighton have a great way of playing football that is different to a lot of teams in the Championship.”

Wolves stepped in to sign him that May and he came off the bench in the opening game of the following season to score an equaliser in a 2-2 draw at Plymouth Argyle. However,

Wolves stepped in to sign him that May and he came off the bench in the opening game of the following season to score an equaliser in a 2-2 draw at Plymouth Argyle. However,  He went on: “Our shortage of strikers was highlighted by the fact that he played the full 90 minutes in all of the first 26 league games that season, but he wasn’t just filling in. He was turning in some outstanding performances, linking up really well with Ings and both were scoring goals aplenty.”

He went on: “Our shortage of strikers was highlighted by the fact that he played the full 90 minutes in all of the first 26 league games that season, but he wasn’t just filling in. He was turning in some outstanding performances, linking up really well with Ings and both were scoring goals aplenty.”

Six of his goals that season came in a run of four consecutive games between 27 November and 27 December, four of them penalties.

Six of his goals that season came in a run of four consecutive games between 27 November and 27 December, four of them penalties. In two years with the Bees, Mundee made 73 starts plus 25 appearances as a sub but, when his old Bournemouth teammate

In two years with the Bees, Mundee made 73 starts plus 25 appearances as a sub but, when his old Bournemouth teammate

GOALKEEPER Alan Blayney only played 15 games on loan to Brighton from Southampton but if finances had been better at the time he could have signed permanently and his career may have taken a different turn.

GOALKEEPER Alan Blayney only played 15 games on loan to Brighton from Southampton but if finances had been better at the time he could have signed permanently and his career may have taken a different turn.