JOE KINNEAR was no stranger to expletive-filled rants so we can only imagine how he reacted when his former Tottenham Hotspur teammate Alan Mullery told him he was a stone overweight and shouldn’t expect any special treatment at Brighton.

The right-back who’d won silverware alongside the former Spurs skipper ended up leaving the Goldstone acrimoniously after his former colleague took over as Albion boss.

Having made 258 appearances in 10 years at White Hart Lane, Kinnear only played 18 games for Brighton after being signed by Mullery’s predecessor, Peter Taylor in August 1975.

He’d followed fellow former Spurs defender Phil Beal to third-tier Brighton, both having been eased out of the door as Tottenham’s new boss Terry Neill re-shaped the award-winning squad built up by the legendary Bill Nicholson and his faithful assistant, Eddie Baily.

Back when Taylor and Brian Clough were turning round the fortunes of Derby County, they had acquired the services of former Spurs hardman Dave Mackay, a friend of Kinnear’s, so he was no stranger to turning to experienced old pros.

“I left Tottenham because although I was good enough to hold down a regular first team place, manager Terry Neill didn’t think so,” Kinnear told Shoot! magazine. “I’m 28-years-of-age and have plenty of soccer at senior level left in me. Brighton have the potential to become as big-time as Spurs once were.”

Three days after signing, the Irishman made his Albion debut at right-back in a 1-0 home defeat to Cardiff City and, while he played in the following game too, previous regular right-back Ken Tiler was restored to the line-up for the next three months.

Nevertheless, his lack of involvement at Brighton didn’t stop the Republic of Ireland selecting him and he made what was his last and 26th appearance for his country as an 83rd minute substitute for Tony Dunne in a 4-0 win over Turkey at Dalymount Park, Dublin, on 29 October (Don Givens scored all four).

Kinnear was on Brighton’s bench a few times in the days of only one substitute, and he managed four consecutive starts in December, but he had to bide his time for his next starting spot, which only came when a bad injury in mid-March brought an end to Tiler’s involvement in Albion’s promotion push.

It was timely because on 23 March a testimonial match for him against Spurs took place at the Goldstone. It had been part of the arrangement made when he signed, and the Albion XI who took to the field in front of 7,124 fans included Kinnear’s old teammates Terry Venables, Mackay and Jimmy Greaves, along with guest star Rodney Marsh.

Spurs were in no mood for sentiment, though, and ran out 6-1 winners, with Kinnear scoring a consolation for Albion from the penalty spot.

As Albion’s promotion bid unravelled, Kinnear played in 10 league matches, only three of which were won. Although he was successful with another penalty, this time against Chesterfield, the Spireites won 2-1 with two penalties of their own.

Fingers were pointed at Kinnear for a gaffe in a decisive Easter game at promotion rivals Millwall which Albion ended up losing 3-1.

In his end-of-season summary, the Evening Argus Albion watcher John Vinicombe pointedly considered it was the injury ruling out Tiler that had been a key turning point in the failure to gain a promotion spot.

Kinnear himself suffered a serious knee injury in the penultimate game of the season, a 1-1 home draw against Gillingham, capping a dismal afternoon in which he also had a penalty saved. His departure on a stretcher on 19 April 1976 was his last appearance in an Albion shirt, other than being pictured kneeling on the end of the front row in the August pre-season team photo.

What happened next was covered in some detail in a 2013 blog post on thegoldstonewrap.com. In short, Mullery had arrived as manager following Taylor’s decision to quit and link up again with Clough, who’d taken over at Nottingham Forest.

Mullery was unimpressed by his former teammate’s level of fitness and attitude and called him out in front of the squad. Peter Ward, the new kid on the block at that point, thought it was the wrong approach and, in Matthew Horner’s book He Shot, He Scored, said: “It seemed that Mullery and Kinnear didn’t get on very well.”

Contractually, Albion still owed Kinnear money but it was evident he wasn’t going to feature while Mullery was in charge and a settlement had to be reached. Eventually Kinnear moved on to become player-manager of non-league Woodford Town, beginning a career in coaching and management that ultimately took him back to the top level of the game, albeit frequently attracting headlines for some extraordinary and controversial behaviour.

But let’s stick with Kinnear the player for the moment. Born in Kimmage, Dublin, on 27 December 1946, he moved to Watford at the age of seven. After leaving school, he became an apprentice machine minder in a print works and played amateur football for St Albans City. It was there he was spotted by the aforementioned Baily, who invited him to join Spurs’ pre-season training. He initially signed as an amateur in 1963, turning professional two years later.

His breakthrough season was 1966-67. He made his debut for the Republic of Ireland on 22 February 1967 in a 2-1 defeat to Turkey and won a regular place in the Spurs side when Phil Beal was sidelined with a broken arm. Kinnear performed well in Beal’s absence and he ended it as a member of the side which beat Chelsea 2-1 in the 1967 FA Cup Final.

“I was 20 when we played in the 1967 FA Cup Final and I got Man of the Match, so it was a great start for me,” Kinnear told tottenhamhotspur.com.

All was going well until January 1969 when in a home game against Leeds United he broke his right leg in two places, and he was out of the side for a long while.

Kinnear’s misfortune provided an opportunity for emerging youngster Ray Evans, as this Spurs archive website recalls: “When he got his chance through an injury to regular right back Joe Kinnear, Evans took over in that position and provided a threat with fast, over-lapping runs along with a notable fierce shot that chipped in with a few goals for the club. Strong in the tackle and quick to recover his position, his height also helped him when teams tried to play diagonal passes in behind him.”

Evans had long spells in the side, especially in the 1973-74 season when Kinnear barely got a look-in, but the Irishman battled for his place and was first-choice right-back in Spurs’ League Cup winning sides of 1971 and 1973, and the UEFA Cup winning line-up in 1972.

The revered Nicholson had encouraged Kinnear to become a coach once his playing days were over, but he struggled to get a foot on the ladder in the UK. Ex-Derby boss Mackay, with whom he used to go to Walthamstow dogs after training, took him on as his assistant in the United Arab Emirates and Malaysia, then later at Doncaster Rovers after Kinnear had spent time in India and Nepal.

Eventually, in 1992, he got his chance at Wimbledon, defying the purists with a brand of football that saw them finish in sixth place in 1993-94 – and Kinnear won the League Managers’ Association Manager of the Year award.

Over seven years, The Dons played 364 games under him, winning 130, drawing 109 and losing 125. Despite not even playing at their own ground – they played home matches at Selhurst Park – Wimbledon continued to defy the critics with their resilience in the Premier League and progress in the cups but in 1999 Kinnear stood down as manager after suffering a minor heart attack.

He later enjoyed success in two years (2001-03) at Luton Town and had colourful spells as manager of Nottingham Forest (2004) and manager (2008-09) then director of football (2013-14) at Newcastle United.

Acres of newsprint and plenty of clips on YouTube record some extraordinary behaviour following his appointment by Mike Ashley at Newcastle. Perhaps one of the best summaries is on planetfootball.com, with reporter Benedict O’Neill saying: “Mike Ashley’s mismanagement of Newcastle has been a long-term affair with many bizarre decisions, but his appointment of the long-forgotten Joe Kinnear — twice! — may just be the strangest of all.”

Kinnear, who was diagnosed with dementia in 2015, died aged 77 on 7 April 2024.

Pictures from my personal scrapbook, matchday programmes and various online sources.

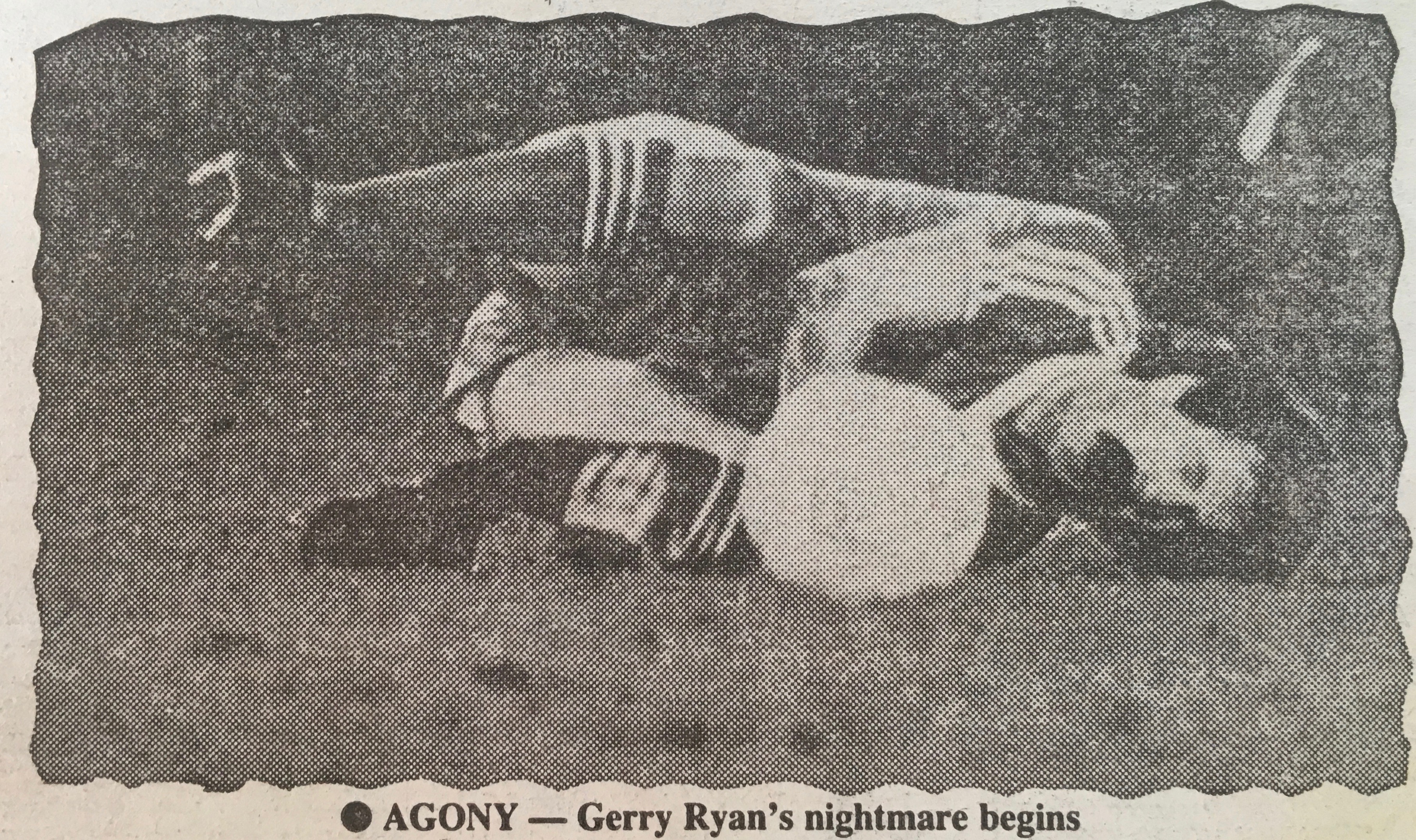

A week after joining the Seagulls, Ryan became an instant hit with Albion fans when he scored on his home debut in a 5-1 win over Preston. He notched a total of nine goals in 34 appearances in that first season and went on to score 39 in a total of 199 games.

A week after joining the Seagulls, Ryan became an instant hit with Albion fans when he scored on his home debut in a 5-1 win over Preston. He notched a total of nine goals in 34 appearances in that first season and went on to score 39 in a total of 199 games.

My personal favourite came on 29 December 1979 at the Goldstone when he ran virtually the entire length of a boggy, bobbly pitch to score past

My personal favourite came on 29 December 1979 at the Goldstone when he ran virtually the entire length of a boggy, bobbly pitch to score past

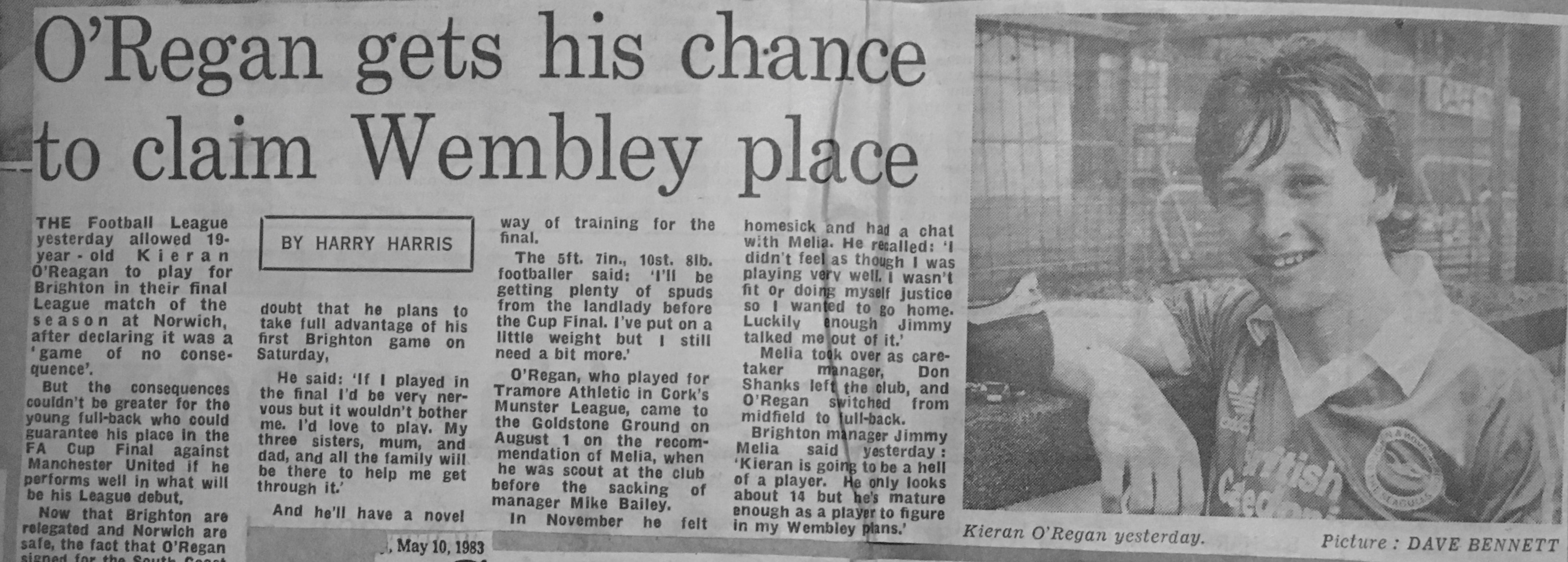

WHEN just 19, unbeknown to thousands of expectant Brighton fans, Kieran O’Regan was on the brink of making a sensational debut for the Seagulls in the FA Cup semi-final.

WHEN just 19, unbeknown to thousands of expectant Brighton fans, Kieran O’Regan was on the brink of making a sensational debut for the Seagulls in the FA Cup semi-final.

In the event, forward

In the event, forward  Making the grade with Brighton caught the eye of the Republic of Ireland selectors and O’Regan was called up to play for his country on four occasions.

Making the grade with Brighton caught the eye of the Republic of Ireland selectors and O’Regan was called up to play for his country on four occasions. However, in 2001, he was offered the chance to be the expert summariser on Huddersfield games for BBC Radio Leeds, and he lined up alongside commentator Paul Ogden for the next 15 years, before hanging up the microphone in May 2016.

However, in 2001, he was offered the chance to be the expert summariser on Huddersfield games for BBC Radio Leeds, and he lined up alongside commentator Paul Ogden for the next 15 years, before hanging up the microphone in May 2016.