FEARLESS NORTHERN Ireland international centre forward Sammy Morgan and his former Port Vale teammate Brian Horton were bought to win promotion for the Albion.

The gamble by manager Peter Taylor didn’t quite pay off and although midfield dynamo and captain Horton went on to fulfil that promise under Alan Mullery, Morgan’s part in the club’s future success was eclipsed by the emergence of Peter Ward.

Morgan, who was in the same Northern Irish primary school year as George Best, was the first to arrive, a £35,000 signing from Aston Villa in December 1975, replacing the out-of-favour Neil Martin alongside Fred Binney. He wasn’t able to find the net in his first seven matches but when he did it was memorable and went down in the annals of Albion history.

He scored both goals in a 2-0 win over Crystal Palace in front of a 33,000 Goldstone Ground crowd that took Albion into second place in the table, manager Taylor saying afterwards: “I am delighted for Morgan. It must have given him a great boost to get a couple of goals like this.”

That breakthrough looked like opening the floodgates for the aggressive, angular forward who went on to score in five consecutive home games in a month.

And when Horton arrived in March 1976, with Albion still in second place and only 11 games to go, promotion looked a strong possibility.

But an Easter hiccup, losing 3-1 to rivals Millwall, followed by three 1-1 draws to end the season, saw Albion drop to fourth, three points behind the south London club, who went up behind Hereford United and Cardiff City.

Short-sighted Morgan – he wore contact lenses to play – might not have seen it coming, but it was something of a watershed moment for him too.

The man who signed him decided to quit, saying: “I signed two players gambling on them to win us promotion. We didn’t get it, and the only consolation I have in leaving is I feel I have helped build a good team which is capable of going up next time.”

Before he managed to kick a ball in anger under new boss Mullery, Morgan suffered a fractured cheekbone in a collision with Paul Futcher in a pre-season friendly with Luton in August 1976. The injury sidelined him for months.

By the time he was fit to resume towards the end of November, young Ward and midfielder-turned-striker Ian Mellor had formed such an effective goalscoring partnership that Morgan could only look on from the substitute’s bench where he sat on no fewer than 29 occasions.

He got on in 18 matches but only scored once, in a 2-1 home win over Chesterfield. Of his two starts that season, one was a New Year’s Day game at Swindon in which Albion were trailing 4-0 when it got abandoned on 67 minutes because of a waterlogged pitch (and he was back to the bench for the rescheduled game at the end of the season).

Nonetheless, Taylor’s promotion premonition was duly achieved at the completion of Mullery’s first season, and Ward had scored a record-setting 36 goals.

Morgan wasn’t involved in Albion’s first two games of the new season – consecutive 0-0 draws against Third Division Cambridge United, in home and away legs of the League Cup – and, by the time of the replay, he had signed for the opponents, who were managed by Ron Atkinson.

So, in a strange quirk of fate, £15,000 signing Morgan’s first match for the Us saw him relishing a bruising encounter up against former teammate Andy Rollings, although Albion prevailed 3-1.

Morgan spoke about the encounter and his long career in the game in a fascinating 2015 televised interview for 100 Years of Coconuts, a Cambridge United fans website.

Morgan’s easing out at Brighton followed a similar pattern to his experience at Aston Villa who replaced him with 19-year-old Andy Gray, a £110,000 signing from Dundee United. Morgan only made three top flight performances for Villa after a pelvic injury had restricted his involvement in Villa’s second tier promotion in 1975 to just 12 games (although he did score four goals – three in the same match, a 6-0 win over Hull City early in the season). He was injured during a 1-1 draw at Fulham in November and subsequently lost his place in the team to Keith Leonard.

Morgan had been 26 when Vic Crowe signed him from Port Vale as a replacement for the legendary Andy Lochhead. The fee was an initial £22,222 in August 1973 with the promise of further instalments of £10,000 for every 10 goals up to 20. Vale’s chairman panicked when the goals tally dried up with the total on nine but Morgan eventually came good and Villa ended up paying the extra.

He made his Villa debut on 8 September 1973 as a sub for Trevor Hockey on the hour in a 2-0 home win over Oxford United, the first of five sub appearances and 25 starts that season, when he scored nine goals.

Villa writer Eric Woodward said of him: “Sammy was never a purist but he was a brave, lively, enterprising sort who put fear into opposing defences.”

He carved his name into Villa legend during a fourth round FA Cup tie against Arsenal at Highbury in January 1974 when he was both hero and villain.

Morgan put the Second Division visitors ahead with a diving header in the 11th minute but in the second half was booked and sent off for challenges on goalkeeper Bob Wilson. After his dismissal, Arsenal equalised through Ray Kennedy.

Esteemed football writer Brian Glanville reckoned: “Morgan had scored Villa’s goal and had played with fiery initiative but, alas, he crossed the line dividing virility from violence.

“He should have taken heed earlier, when booked for fouling Wilson. But a few minutes later, going in unreasonably hard and fractionally late as Wilson dived, he knocked the goalkeeper out and off he went.”

An incensed Morgan saw it differently, though, telling Ian Willars of the Birmingham Post: “Neither my booking nor the sending-off were justified. I never touched Wilson the first time and the second time I was going for the ball, not the man. It was a 50-50.

“I actually connected with the ball not Wilson. I went over to check if he was hurt and, in my opinion, he was play-acting.”

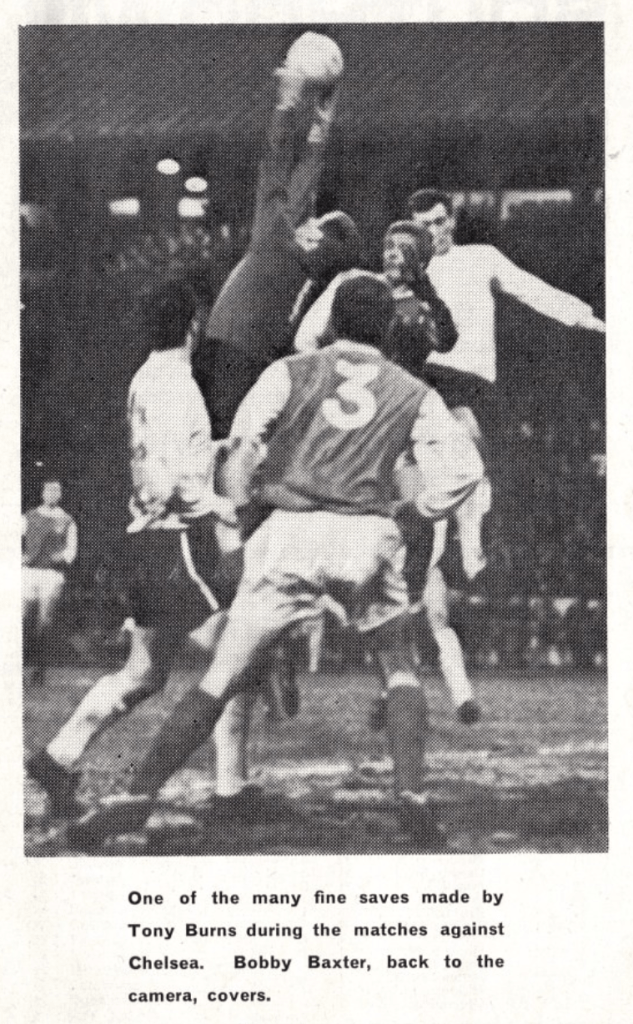

Morgan had sweet revenge four days later. No automatic ban meant he was able to play and score in the replay at Villa Park which Villa won 2-0 in front of a bumper crowd of 47,821.

Randall Northam of the Birmingham Mail wrote: “Providing the sort of material from which story books are written, the Northern Ireland international Sammy Morgan, who was sent off on Saturday, scored in the 12th minute.

“He had scored in the opening game in the 11th minute and to increase the feeling of déjà vu it was another diving header.” Fellow striker Alun Evans scored Villa’s second.

Northam added: “It was never a great match but the crowd’s enthusiasm lifted it to a level which often made it exciting and they had their reward for ignoring the torrential rain in a driving Villa performance which outclassed their First Division opponents.”

For his part, an unrepentant Morgan said: “It was obvious that we had to put Wilson under pressure as anyone would have done in the circumstances. My goal could not have happened at a better time.”

How heartening to hear in that 100 Years of Coconuts interview that when Morgan was struck down with cancer 40 years later, one of several well-wishing calls he received came from Bob Wilson.

Born in East Belfast on 3 December 1946, Morgan went to the same Nettlefield Primary School as George Best and the first year at Grosvenor High. But Morgan left Belfast as an 11-year-old with his family, settling in Gorleston, near Great Yarmouth (his mother’s birthplace).

His Irish father, a professional musician, took over the running of the Suspension Bridge tavern in Yarmouth and Morgan’s footballing ability continued to develop under the watchful eye of his teacher, the Rev Arthur Bowles, and he went on to represent Gorleston and Norfolk Schools.

Morgan went to the same technical high school in Gorleston that also spawned his great friend Dave Stringer (a former Norwich player and manager), former Arsenal centre back Peter Simpson and ex-Wolves skipper Mike Bailey, who managed Brighton in the top flight in 1981 and 1982.

Morgan’s early hopes of a professional career were dented when he had an unsuccessful trial at Ipswich Town. Alf Ramsey was manager at the time and the future England World Cup winning boss considered him too small. He also had an unsuccessful trial with Arsenal.

Morgan continued to play as an amateur with Gorleston FC and although on leaving school he initially began working as an accountant he decided to study to become a maths and PE teacher at Nottingham University. It was Gorleston manager Roger Carter who recommended him to the then Port Vale manager Gordon Lee, who was a former Aston Villa colleague.

“I loved my time under Roger and my playing days under him were the most enjoyable years of my footballing career even though I went on to play at a higher level,” said Morgan.

He was the relatively late age of 23 when, in January 1970, he had a successful trial with Vale and signed amateur forms. But by July that year he was forced to make a decision between full-time professional football or teaching. He chose football and made a scoring Football League debut against Swansea in August 1970.

However, that summer he was spotted as a future talent by Brian Clough and Peter Taylor when he played against their Derby County side in a pre-season friendly. Clough inquired about taking him on loan but he cemented his place in the Vale side and it didn’t go any further.

nifootball.blogspot.com wrote of him: “The burly centre-forward, he weighed in at up to thirteen and a half stone during his career, proved highly effective in an unadventurous Vale side.”

His strength and aggression in Third Division football caught the attention of Northern Ireland boss Terry Neill and he scored on his debut for his country in a February 1972 1-1 draw with Spain, played at Hull because of the troubles in the province, when he teamed up with old school chum Best.

Morgan remembered turning up at the team hotel, the Grand in Scarborough, and encountering a press camera posse awaiting Best’s arrival – and he didn’t show! The mercurial talent did make it in time for the game though, when another debutant was Best’s 17-year-old Manchester United teammate Sammy McIlroy, who earned the first of 88 caps.

In the home international tournament that followed, Morgan was overlooked in favour of Derek Dougan and Albion’s Willie Irvine who, having helped Brighton win promotion from Division Three (and scored what was selected as Match of the Day’s third best goal of the season against Aston Villa) earned a recall three years after his previous appearance.

In October of 1972, though, Morgan was selected again and took his cap total to seven while at Vale Park, for many years a club record.

While at Brighton, he earned two caps during the 1976 home international tournament, starting in the 3-0 defeat to Scotland and going on as a sub in a 1-0 defeat to Wales.

He earned his 18th and final cap two years later during his time at Sparta Rotterdam in a 2-1 win over Denmark in Belfast. The legendary Danny Blanchflower was briefly the Irish manager and he selected Morgan up front alongside Gerry Armstrong but he reflected that he didn’t play well, was struggling with a hamstring injury at the time, and was deservedly subbed off on the hour mark.

Morgan’s knack for helping sides win promotion had worked at Cambridge too, where he partnered Alan Biley and Tom Finney (no, not that one!) in attack, but after Atkinson left to manage West Brom, he fell out with his successor, John Docherty, and in August 1978 made the switch to Rotterdam.

After one season there, he moved on to Groningen in the Eeste Divisie (level two) and although he helped them win the title, he suffered a knee injury and called time on his professional playing days.

He returned to Norfolk to teach maths and PE in Gorleston, at Cliff Park High School and then Lynn Grove High School, and carried on playing with his first club, Gorleston, where, in 1981, he was appointed manager.

As well as coaching Great Yarmouth schoolboys, he also got involved in coaching Norwich City’s schoolboys in 1990 and in January 1998 he left teaching to work full-time as the club’s youth development manager. As the holder of a UEFA Class A licence, he went on to become the club’s first football academy director, a position he held until May 2004.

In October that year, Morgan was unveiled as Ipswich Town’s education officer, a role that involved ensuring Town’s young players received tuition on more than just football as they went through the academy system. In 2009, he became academy manager and during his three years notable youngsters who made it as professionals included strikers Connor Wickham and Jordan Rhodes.

He admitted in an interview with independent fan website TWTD: “If I’ve contributed to anybody in particular it probably would be the big number nine [Wickham] and Jordan because I was a number nine, and I kick the ball through them – I play the game through the number nines.”

He went on: “I’m very proud to have played a part in the development of a lot of young players. I’m equally proud of those lads who haven’t quite got there in the professional ranks but have maybe gone on to university and have forged other careers and are still playing football at non-league level, still enjoying their football. That means a lot to me as well.”

Morgan continued: “I finished playing in 1980 and I’ve been in youth development since then. I did the Norfolk schools, Great Yarmouth schools, representative sides and the Bobby Robson Soccer Schools. That’s 32 years, I’ve given it a fair crack and I love my football as much now as I ever did.

“I’ve been privileged to work with young people, very privileged. It’s kept me young, kept my passion and kept my enthusiasm going. One thing you could never accuse me of is not having any enthusiasm or passion for the game, and that will remain.”

In 2014, Morgan was diagnosed with stomach cancer and underwent chemo to tackle it. Through that association, in September 2017 he gave his backing to Norfolk and Suffolk Youth Football League’s choice of the oesophago-gastric cancer department at the Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital (NNUH) as its charity of the year.

Even when he could have had his feet up, he was helping to coach youngsters at independent Langley School in Norwich.

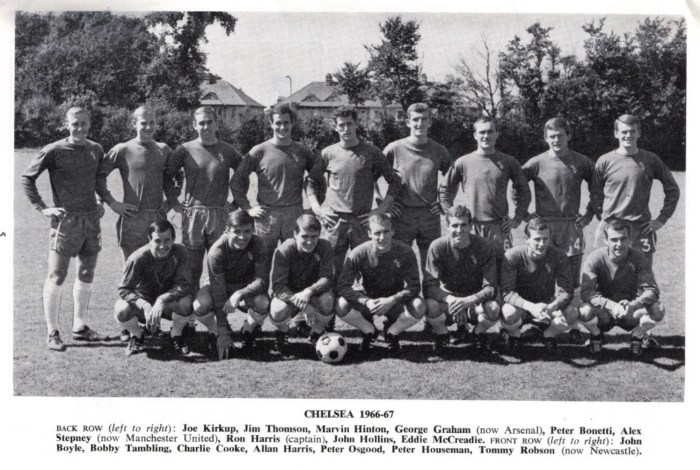

Although initially a midfielder, coach Ken Shellito turned him into a defender and Chivers’ versatility in defence meant he could play centrally or in either full-back berth. Among his early contemporaries were John Bumstead,

Although initially a midfielder, coach Ken Shellito turned him into a defender and Chivers’ versatility in defence meant he could play centrally or in either full-back berth. Among his early contemporaries were John Bumstead,