BEING LET GO by the Albion as an apprentice didn’t stop Kevin Russell from going on to enjoy a multi-club league career as a player and a coach involved in no fewer than eight play-off finals and promotions.

A talented teenager good enough to earn selection for the England Youth team, Russell didn’t progress beyond Brighton’s youth and reserve sides between 1982 and 1984.

Although he was a regular goalscorer in the junior sides, a falling out with manager Chris Cattlin saw him depart the club without earning a competitive first team call-up.

Hailing from Paulsgrove in north Portsmouth, Russell returned home and linked up with his hometown club to complete his scholarship under World Cup winner Alan Ball.

Ball also gave him his first team debut but he only had eight first team outings for Pompey. It wasn’t until he joined Fourth Division Wrexham for £10,000 that his career began to take off and he was in the Wrexham side that reached the 1989 play-off final where they lost 2-1 to Frank Clark’s Leyton Orient. In the first of two spells in north Wales, playing at centre forward, Russell scored an impressive 47 goals in 102 games.

An ever-present in the 1988-89 season, his 25 goals in a total of 60 league and cup matches was recognised by his peers when he was selected in the PFA divisional team of the year.

That caught the eye of David Pleat at Leicester City, then playing in the ‘old’ Second Division, and a fee of £175,000 took him to Filbert Street.

At Leicester he played wide right rather than in the centre but he still had a knack for scoring goals and he eventually became something of a cult hero with Foxes supporters for the goals he scored in City’s escape from second tier relegation in 1991 and in their run up to the 1992 play-off final.

However, only a month after joining Leicester he had to undergo a hernia operation that put him out of action for eight weeks. When fit, he was sent out on a month’s loan to Peterborough …and suffered a broken leg!

When ready to play again, his effort to resume match fitness saw him go on another month’s loan, to Fourth Division Cardiff City. In the meantime, Pleat was sacked and Gordon Lee took over. Russell returned as the Foxes fought to avoid relegation to the third tier.

Perhaps inevitably one of the vital goals he scored (on 6 April 1991) was against promotion-seeking Albion in a 3-0 win that helped the Foxes in the hunt to stave off the dreaded drop.

Two years later, after he had moved on to Burnley via Stoke City, Russell’s first goals for the Clarets (above) were also scored in a 3-0 win over the Seagulls.

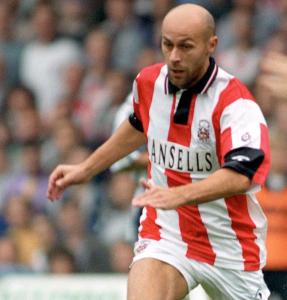

Born in Portsmouth on 6 December 1966, the nickname Rooster was coined at an early age because his hair formed something of a quiff when he was a boy – ironically, he went prematurely bald but the name stuck.

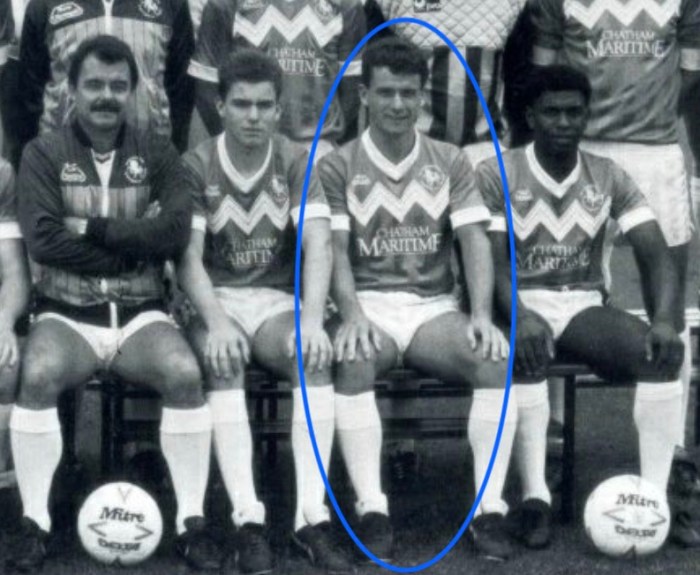

Russell’s first appearances in Albion’s colours came in the early autumn of 1982 playing in the junior division of the South East Counties League. He was still a 15-year-old schoolboy at the time.

By the spring of 1983, while the Albion first team were edging towards the FA Cup final at Wembley, Russell had stepped up to the reserves, as the matchday programme reported after he’d been involved in a close game against an experienced West Ham second string.

“Kevin Russell is just sixteen and he doesn’t leave school until he has taken his examinations next month,” it said. “But at Upton Park he found himself playing against such experienced men as Trevor Brooking and Jimmy Neighbour.

“Many schoolboys would have given their right arm to play on the same field as Brooking and there was Kevin playing on equal terms.

“Although we lost 2-1, it should be remembered that in Kieran O’Regan, Mark Fleet, Matthew Wiltshire, Gerry McTeague, Gary Howlett, Chris Rodon and Kevin Russell we had seven players under 20, while the Hammers had Paul Allen, Paul Brush and Pat Holland, all of whom have played in European competition, as well as Neighbour and Brooking in their line-up.”

John Shepherd was in charge of the side, aided by John Jackson, who had been signed as goalkeeping cover and was helping out with coaching too.

Russell’s official arrival as an apprentice at Brighton earned a mention in the matchday programme for the home game with Chelsea on 3 September 1983 and he was one of five apprentices on the staff that autumn, together with Dave Ellis, Darron Gearing, Gary Mitchell and Mark Wakefield. Martin Lambert had stepped up to sign as a full professional that summer.

In those days, the youth team played home matches at Lancing College and were looked after by Shepherd and Mick Fogden before experienced George Petchey was brought in to oversee youth development and run the reserves.

It was while a Brighton player that Russell won the first of six England under-18 caps (five starts plus one as sub), and he scored in the first of them – a 2-2 draw with Austria on 6 September 1984 – and in his fourth game, six days later, which England lost 4-1 to Yugoslavia. His strike partner in that side was Manchester City’s Paul Moulden, later an Albion loanee.

With the likes of Terry Connor, Alan Young and Frank Worthington in the first team, and promising youngsters in the reserves, such as Lambert, Rodon and Michael Ring, it is perhaps not surprising that Russell couldn’t break through.

He did have one outing in first team company, though, in a testimonial match for Gary Williams: he scored (along with Young and Connor) in a 3-3 draw against an ex-Albion XI.

The same game saw defender Jim Heggarty appear: like Russell he also went on to play for Burnley without playing a competitive first team game for the Albion.

While on that theme, a frequent partner of Russell’s in the reserves was Ian Muir, another striker who slipped through Albion’s net and ended up scoring goals for Burnley.

After his departure from the Albion in October 1984, Russell made the most of the opportunity Portsmouth presented him to learn from the former Everton, Arsenal and Southampton midfield dynamo Ball.

“I had three years there under him which was fantastic,” Russell told Leicester City club historian John Hutchinson in March 2018. “He was brilliant as a coach and it was very educational. I got the rest of my (under-18) caps at Portsmouth.

“Alan Ball treated us well. I was playing men’s football at 18. I played a few games in the first team and we managed to get promoted into what is now the Premier League.”

Although disappointed to be advised to move on to get more games, Russell’s switch to north Wales was the launchpad for his career, and the beginning of an association with Wrexham that lasted many years.

“It was a gamble worth taking because it meant first team football,” said Russell. “Dixie McNeill was the manager. He used to be a famous striker for them. He was fantastic for me and was an old school kind of manager; a proper man’s manager. It was a good time.”

After Russell’s part in keeping Leicester in the second tier in 1991, he found himself on the outside looking in when Brian Little replaced Gordon Lee as manager and to get some playing time went on a month’s loan to Hereford United and then spent a month at Lou Macari’s Stoke City.

But Little recalled him in February and in his first game back he once again found the net against a former club, scoring in a 2-2 draw with Portsmouth. He kept his place through to the play-off final at Wembley, where they faced Kenny Dalglish’s Blackburn Rovers, and lost to a “dodgy penalty” scored by ex-Leicester player Mike Newell.

“It was a very scrappy game. Both teams were under a lot of pressure and never really got into their rhythm,” said Russell. “We had worked so hard that season to get to where we did get to. The result was a big disappointment, but it was an occasion that I’ll never forget.”

It also turned out to be his last game for Leicester because that summer he returned to third tier Stoke on a permanent basis. He is fondly remembered for his part in Stoke winning promotion in 1992-93, scoring six goals in 39 league and cup matches (plus 11 as a sub), but he moved on again, this time to Burnley.

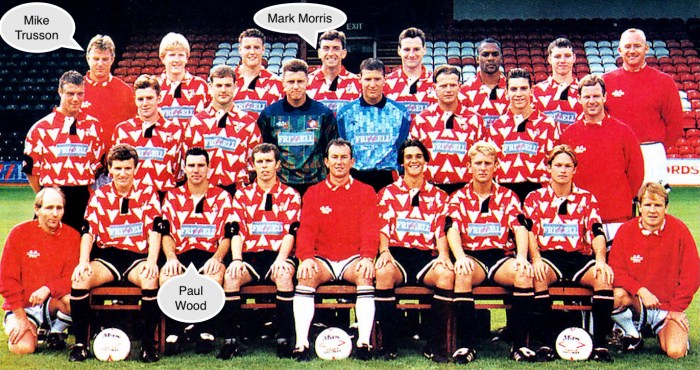

Third-tier Burnley signed him from Stoke for £150,000 (or was it £95,000 – I’ve seen both prices quoted) in June 1993 and, although he only stayed for eight months at Turf Moor, he scored eight goals in 35 games (plus two as sub) in Jimmy Mullen’s Clarets side.

Two of those goals – his first for Burnley – were scored against the Albion. I was at Turf Moor for a midweek game on 14 September 1993 when Russell scored with only a minute on the clock and he got a tap-in on 47 minutes in a 3-0 stroll for the home side. Steve Davis got Burnley’s third.

Brighton were a very different club to the one Russell had left in 1984, though. With a win in a League Cup match their only victory in the opening eight matches, it was the beginning of the end of Barry Lloyd’s tumultuous reign in charge, against a backdrop of financial hardship and boardroom mismanagement off the pitch.

Russell’s habit of scoring against his former clubs manifested itself again two days after Christmas, when he netted in a 2-1 home win over Wrexham. He scored again five days later in a New Year’s Day 3-1 home win over Lancashire rivals Blackpool.

But he was not around to be part of the side promoted via the play-offs, having moved back south, to Bournemouth, for £125,000 in March 1994.

• Another move, a return to north Wales and a career in coaching as Russell’s story continues.

“NEVER in my wildest dreams – or should that be nightmares? – did I think that, more than 20 years later, that miss in front of goal would still be getting replayed on television and mentioned in the media wherever I go.”

“NEVER in my wildest dreams – or should that be nightmares? – did I think that, more than 20 years later, that miss in front of goal would still be getting replayed on television and mentioned in the media wherever I go.” He was at Kilmarnock for five years, scoring 36 goals in 161 appearances, during which time he earned international honours with Scotland’s under-23 side, twice starting and three times going on as a substitute.

He was at Kilmarnock for five years, scoring 36 goals in 161 appearances, during which time he earned international honours with Scotland’s under-23 side, twice starting and three times going on as a substitute.

After United had taken the lead, and Gary Stevens had equalised for Brighton, the game went into extra time and the stage was set for one of the most talked about moments in the club’s history.

After United had taken the lead, and Gary Stevens had equalised for Brighton, the game went into extra time and the stage was set for one of the most talked about moments in the club’s history.

Thirty-eight of his 46 appearances for City came in the 1984-85 season, when he was top scorer with 14 goals.

Thirty-eight of his 46 appearances for City came in the 1984-85 season, when he was top scorer with 14 goals.

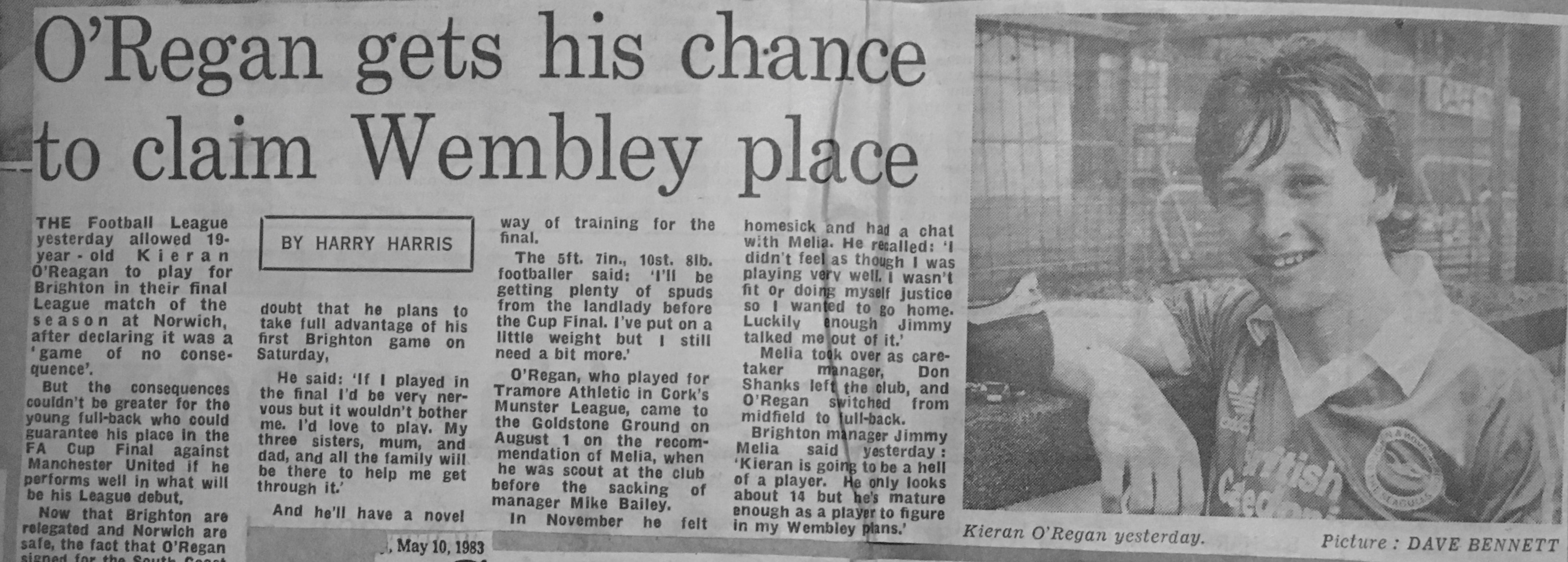

WHEN just 19, unbeknown to thousands of expectant Brighton fans, Kieran O’Regan was on the brink of making a sensational debut for the Seagulls in the FA Cup semi-final.

WHEN just 19, unbeknown to thousands of expectant Brighton fans, Kieran O’Regan was on the brink of making a sensational debut for the Seagulls in the FA Cup semi-final.

In the event, forward

In the event, forward  Making the grade with Brighton caught the eye of the Republic of Ireland selectors and O’Regan was called up to play for his country on four occasions.

Making the grade with Brighton caught the eye of the Republic of Ireland selectors and O’Regan was called up to play for his country on four occasions. However, in 2001, he was offered the chance to be the expert summariser on Huddersfield games for BBC Radio Leeds, and he lined up alongside commentator Paul Ogden for the next 15 years, before hanging up the microphone in May 2016.

However, in 2001, he was offered the chance to be the expert summariser on Huddersfield games for BBC Radio Leeds, and he lined up alongside commentator Paul Ogden for the next 15 years, before hanging up the microphone in May 2016.

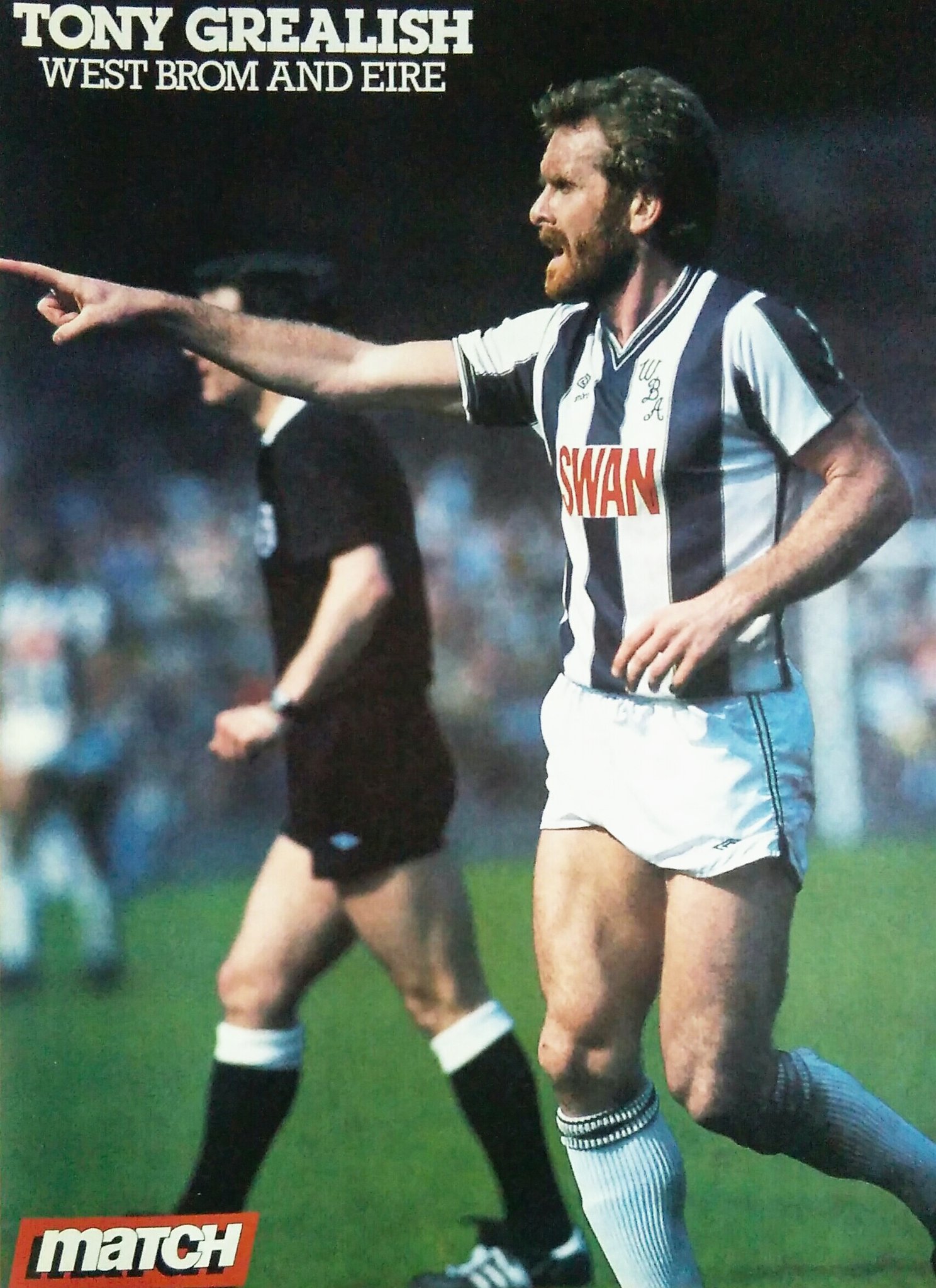

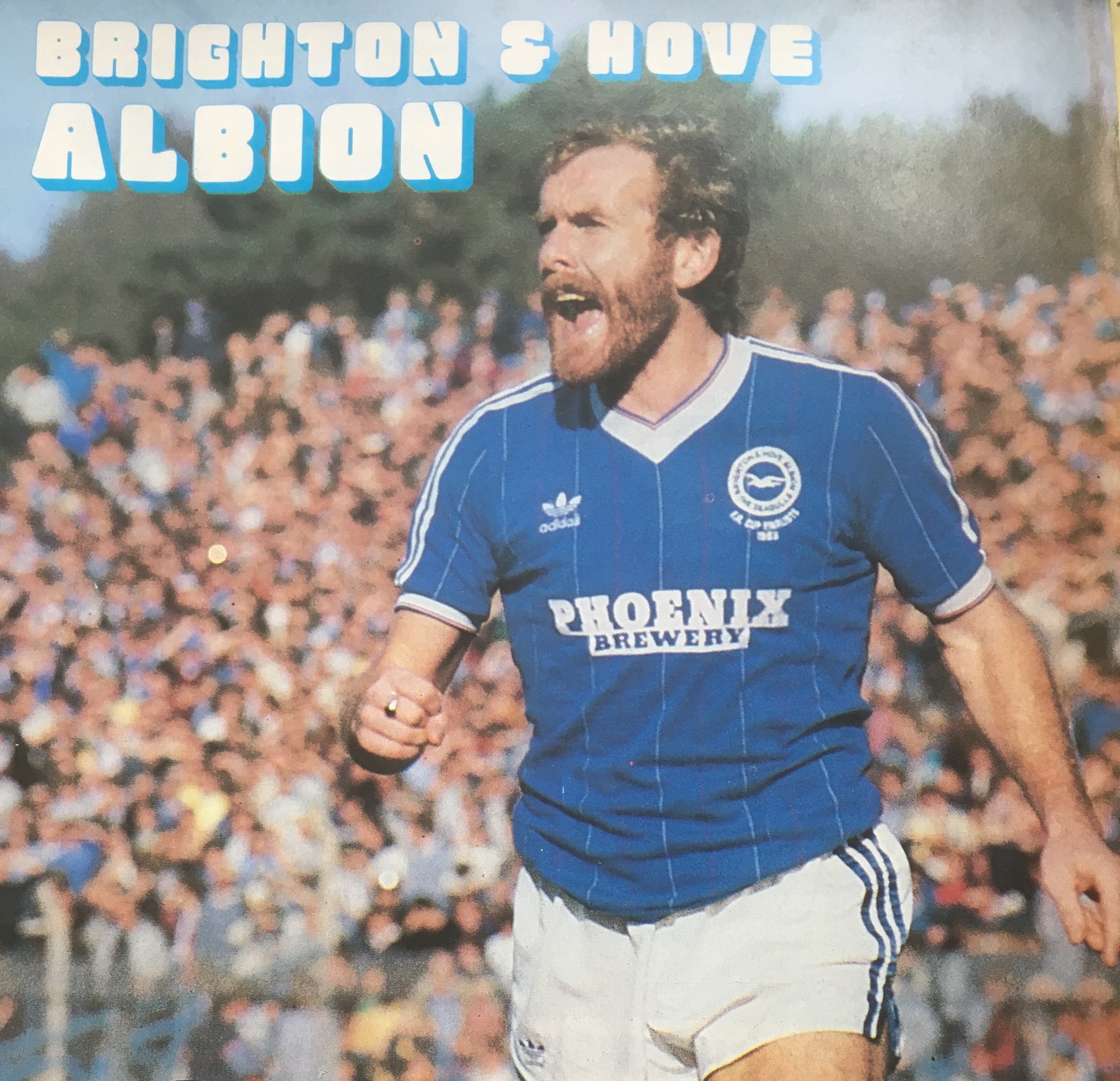

THE PLAYER who led out Brighton at Wembley for the 1983 FA Cup Final against Manchester United was an experienced Republic of Ireland international who went on to play for West Bromwich Albion.

THE PLAYER who led out Brighton at Wembley for the 1983 FA Cup Final against Manchester United was an experienced Republic of Ireland international who went on to play for West Bromwich Albion.