PROLIFIC goalscoring centre-forward Fred Pickering, who at his peak scored hat-tricks on his Everton and England debuts, ended his career after an unsuccessful two-month trial with Brighton.

Pickering was a transfer record signing for Everton (the previous season’s league champions) when he joined them from Blackburn Rovers for £85,000 in March 1964.

On his debut for Harry Catterick’s side, he scored three past Nottingham Forest’s Peter Grummitt in a 6-1 thrashing.

Eight years later, a player who’d played for his country and, but for injury, might have been involved in the 1966 World Cup, scored once for Brighton’s reserve side: in a 3-0 home win over Colchester United on 8 March 1972.

Brighton won promotion from the old Third Division two months later thanks in no small part to 19 goals scored by Kit Napier and 17 from Willie Irvine (Pickering’s former Birmingham City teammate Bert Murray netted 13 and Peter O’Sullivan hit 12).

Throughout the season, manager Pat Saward had been hankering for something a bit extra in the forward line. While he appreciated the skill of Napier and Irvine, he said “none had the devil in him. We wanted more thrust.”

Pickering was the second seasoned striker Saward had run the rule over, wondering whether their experience of goal plundering at the highest level several years before might be revived in third tier Albion’s quest for promotion.

Earlier in the season, he tried recruiting an ageing Ray Crawford but contract issues with the player’s last club, Durban City, meant the former Portsmouth, Ipswich, Wolves and Colchester centre-forward ended up joining the staff as a scout and coach instead.

In February 1972, 31-year-old Pickering, by then not even getting a game in Blackburn’s Third Division side, was given a chance by Saward to show he still had the goalscoring ability he had demonstrated so effectively earlier in his career.

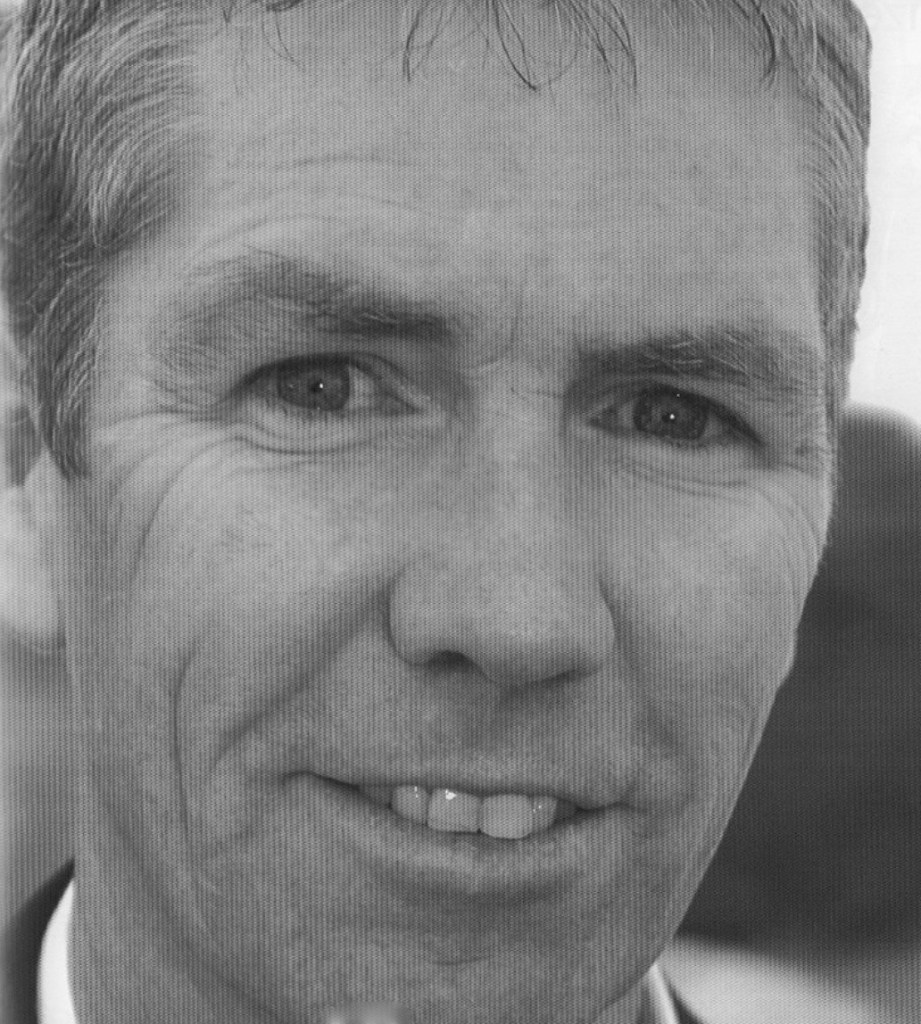

Photographs of a rather heavy-looking Pickering training appeared in the Evening Argus and the former England striker was interviewed on Radio Brighton (as it was then) about his illustrious career. Although he played for the reserves, he wasn’t deemed fit enough to make it into the first team.

Saward eventually got the thrusting forward he sought on March transfer deadline day when he signed Tranmere Rovers’ Ken Beamish, who, at 24, was younger and fitter, and quickly endeared himself to Albion fans by scoring a handful of late goals which helped clinch promotion.

But what of Pickering? Born in Blackburn on 19 January 1941, he played junior football in his hometown before joining Rovers as an amateur aged 15.

As a schoolboy, he’d been an inside forward (a no.8 or no.10 in today’s parlance) but he was a full-back when he signed as a professional for Rovers on his 17th birthday.

Indeed, he was at left-back in the Rovers side that won the FA Youth Cup in 1959, beating West Ham United 2-1 on aggregate over two legs.

Alongside him for Rovers were future Spurs and Wales centre-half Mike England and Keith Newton, who also later moved to Everton and played for England at the 1970 World Cup. West Ham included Bobby Moore and Geoff Hurst in their line-up.

With the likes of Dave Whelan and Bill Eckersley ahead of Pickering in the Blackburn pecking order, his chances of a first team breakthrough were limited.

But after a successful outing for the reserves up front, and with wantaway Irish striker Derek Dougan dropped, Pickering was given a chance as a centre forward – and he never looked back.

He scored twice in a 4-1 win over Manchester City and went on to strike up successful partnerships with Ian Lawther, initially, and then Andy McEvoy.

“It was a big turning point for me to be playing centre forward,” Pickering told the Lancashire Telegraph. “Especially when you consider in 1961, Dally Duncan (Blackburn manager, and later Brighton guesthouse owner) told me that Plymouth wanted me and that I was free to leave. I didn’t want to go because Blackburn was my club.

“I only left in the end because the club wouldn’t give me a rise of a couple of quid. It was absurd.”

By then Pickering had scored 74 goalsin158 appearances – some strike rate – which meant he always held a special place in the hearts of the Ewood Park faithful, as reporter Andy Cryer described in a 2011 article for the Lancashire Telegraph.

“Had fate been kinder to him he could easily have been a national darling too,” wrote Cryer.

“When hat-trick hero Geoff Hurst was firing England to World Cup final glory in 1966, an injured Pickering was left reflecting on what might have been after an incredible journey took him from Rovers reserves to international stardom.”

Pickering, nicknamed Boomer for his powerful right foot, had scored five goals in three England appearances and looked set for inclusion in England’s 1966 World Cup squad having been named in Sir Alf Ramsey’s provisional selection.

But he suffered a knee injury in an FA Cup quarter final replay against Manchester City which not only caused him to miss Everton’s FA Cup final win that Spring, but also meant he had to withdraw from the England squad. Cryer reckons it also led to the subsequent demise of his career.

Pickering told the reporter: “I played three games for England and I scored in every game I played, I scored five goals and I was playing well. I was named in the World Cup squads. I was going and from that day it was the following weekend when the knee started to go.

“I watched all the Brazil games at Goodison. England struggled in their first game against Uruguay and that is when Jimmy Greaves got injured.

“Obviously that is how Hurst got in, he wasn’t even really in the set up before. There was every chance if I had been fit it that might have been me who had got in. I wouldn’t say I would have done what Geoff Hurst did but you never know what might have happened.”

Pickering had made his England debut two months after moving to Everton, in a 10-0 demolition of the USA on 27 May 1964. It was the same match that saw future Albion manager Mike Bailey play his first full international for his country. Roger Hunt went one better than Pickering by scoring four, Terry Paine got two and Bobby Charlton the other. Eight of that England side made it to the 1966 World Cup squad two years later – alas Pickering didn’t.

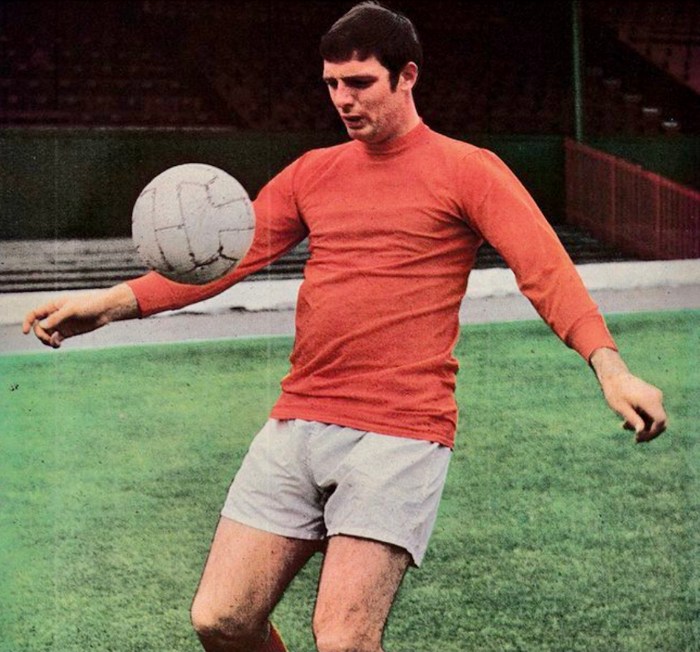

The same scoring rate he had enjoyed at Blackburn continued at Everton and in his first full season he scored 37 goals in all competitions – the most by an Everton player since Tommy Lawton scored 38 in 1938-39.

In three years with the club, he scored 70 times in 115 matches but his exclusion from the 1966 FA Cup final squad soured his relationship with manager Catterick, as covered in detail by the efcstatto.com website. Injuries disrupted his involvement at the start of the following season, and a cartilage operation put him out of action for nearly six months.

Although he made his comeback in March 1967, his Everton days were numbered and, in August 1967, moneybags Birmingham City bought him for £50,000 to form a hugely effective forward line with Barry Bridges and Geoff Vowden.

Pickering and Bridges played in all 50 of Birmingham’s matches in the 1967-68 season; the aforementioned Bert Murray 47. Bridges was top scorer with 28 goals and Pickering netted 15.

The Second Division Blues made an eye-catching run to the semi-finals of the FA Cup, but they lost 2-0 to West Brom (who went on to beat Everton 1-0 in the final).

The following season, Pickering scored 17 times in 40 appearances (Phil Summerill also scored 17, and Jimmy Greenhoff 15) but City finished a disappointing seventh.

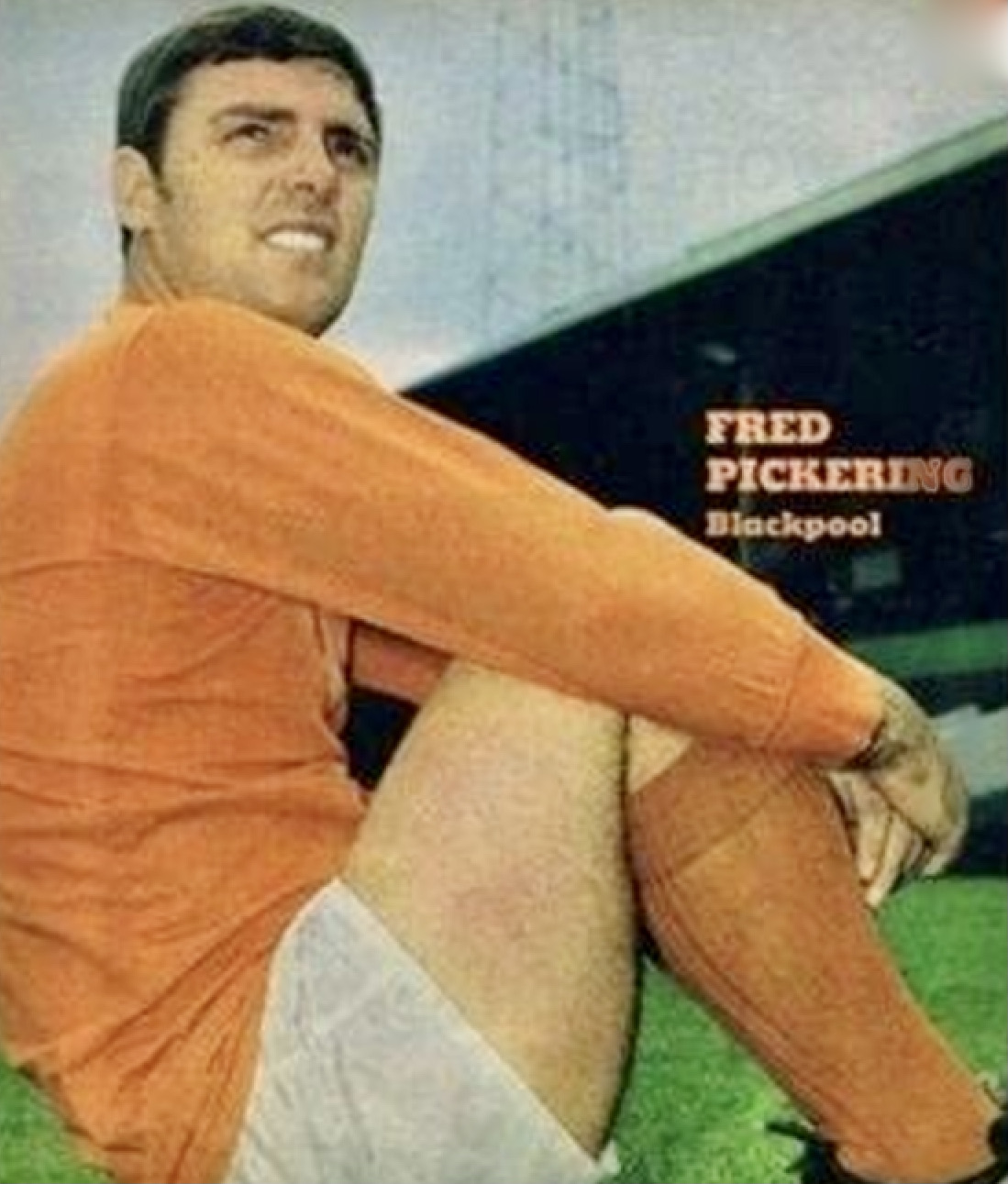

That signalled the end of the striker’s time in the Midlands and he returned to his native north west with Blackpool, who paid £45,000 for his services.

It was money well spent as Pickering top-scored with 18 goals as the Tangerines won promotion back to the elite, finishing runners up to Huddersfield Town. His most memorable performance was on 13 April 1970 when he scored a hat-trick away to local rivals Preston North End in front of a Deepdale crowd of 34,000. It earned Blackpool promotion while simultaneously relegating North End to the third tier.

But the 1970-71 season didn’t go well for Blackpool or Pickering. The club got through three managers and only won four matches all season, which eventually saw them finish bottom of the pile and relegated along with fellow Lancastrians Burnley. Pickering found himself fined and excluded for breaches of club discipline (mainly involving missing training) and before the season was over he was sold back to his first club, Blackburn.

That was a blow to Preston, who had just loaned Willie Irvine to Brighton and were keen to install Pickering as his replacement. But it was to Rovers, for £9,000, that he went, but he couldn’t prevent the Ewood Park outfit being relegated to the third tier.

He scored just twice in 11 League games in his second spell at Blackburn before that two-month trial at Brighton.

After he retired from football, he became a forklift truck driver. Warm tributes were paid when Pickering died aged 78 on 9 February 2019. Well-known football obituarist Ivan Ponting said of him: “At his rampaging best, Fred was an irresistible performer.

“Though neither outstanding in the air, nor overly-physical for a man of his power, not even particularly fast, he could disrupt the tightest of defences with his determined running and a savage right-foot shot that earned him the nickname of ‘Boomer’.

“Boasting nimble footwork for one so burly – he could nutmeg an opponent as comprehensively as many a winger – he was especially dangerous when cutting in from the flank, a manoeuvre that yielded some of his most spectacular goals.”

In March 2022, a road in the Mill Hill district of Blackburn, where he lived all his life, was named after him and his family spoke of their pride as they unveiled the street sign in his honour.

Even a crocked Chivers (by his own admission, a troublesome Achilles tendon restricted his fitness) could do a job for the Albion in an emergency, the young manager believed.

Even a crocked Chivers (by his own admission, a troublesome Achilles tendon restricted his fitness) could do a job for the Albion in an emergency, the young manager believed.

After playing regularly for Southampton’s youth side, his breakthrough came in September 1962 when just 17. He made his first-team debut against Charlton Athletic and signed as a full-time professional in the same week. He became a first-team regular the following season.

After playing regularly for Southampton’s youth side, his breakthrough came in September 1962 when just 17. He made his first-team debut against Charlton Athletic and signed as a full-time professional in the same week. He became a first-team regular the following season.