JOHN RUGGIERO was one of four signings Alan Mullery made for newly promoted Albion in the summer of 1977.

That one of the quartet was Mark Lawrenson from Preston North End for £115,000 rather eclipsed Ruggiero’s arrival from recently relegated Stoke City for £30,000.

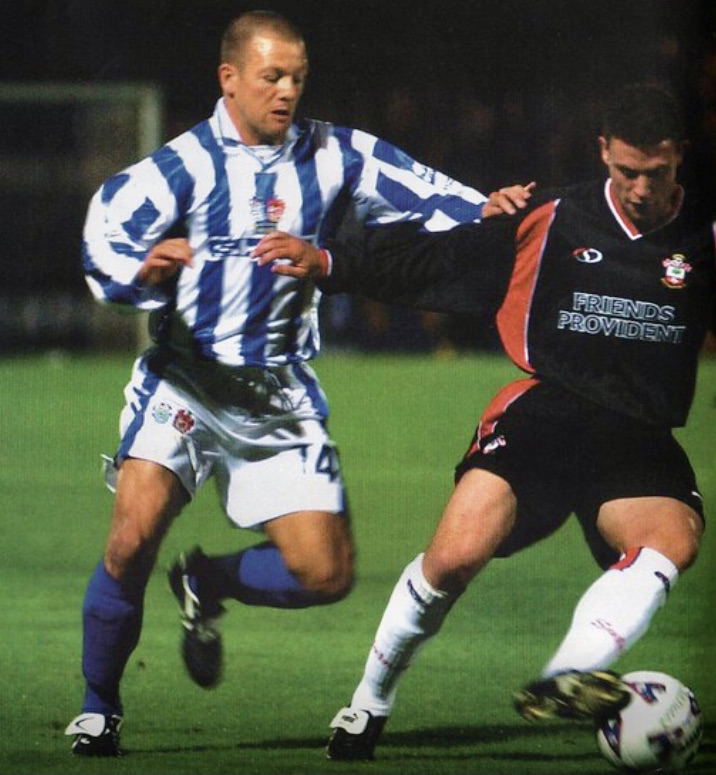

Nonetheless, Ruggiero made an immediate impact, scoring on his league debut as a substitute for Peter O’Sullivan to earn the Seagulls a 1-1 draw at Southampton.

Ruggiero had begun the season in the starting line-up in Albion’s home and away goalless draws against Ron Atkinson’s Cambridge United in the League Cup before relinquishing a starting berth for the opening Division Two fixture at The Dell.

His 77th minute equaliser, after Alan Ball had put the home side ahead just before half time, was added to a fortnight later and, for a brief moment, he was joint top scorer with Steve Piper – on two goals.

The pair were both on the scoresheet to help the Seagulls to a 2-1 win at Mansfield Town on 3 September; the home side’s first defeat at Field Mill in 38 matches.

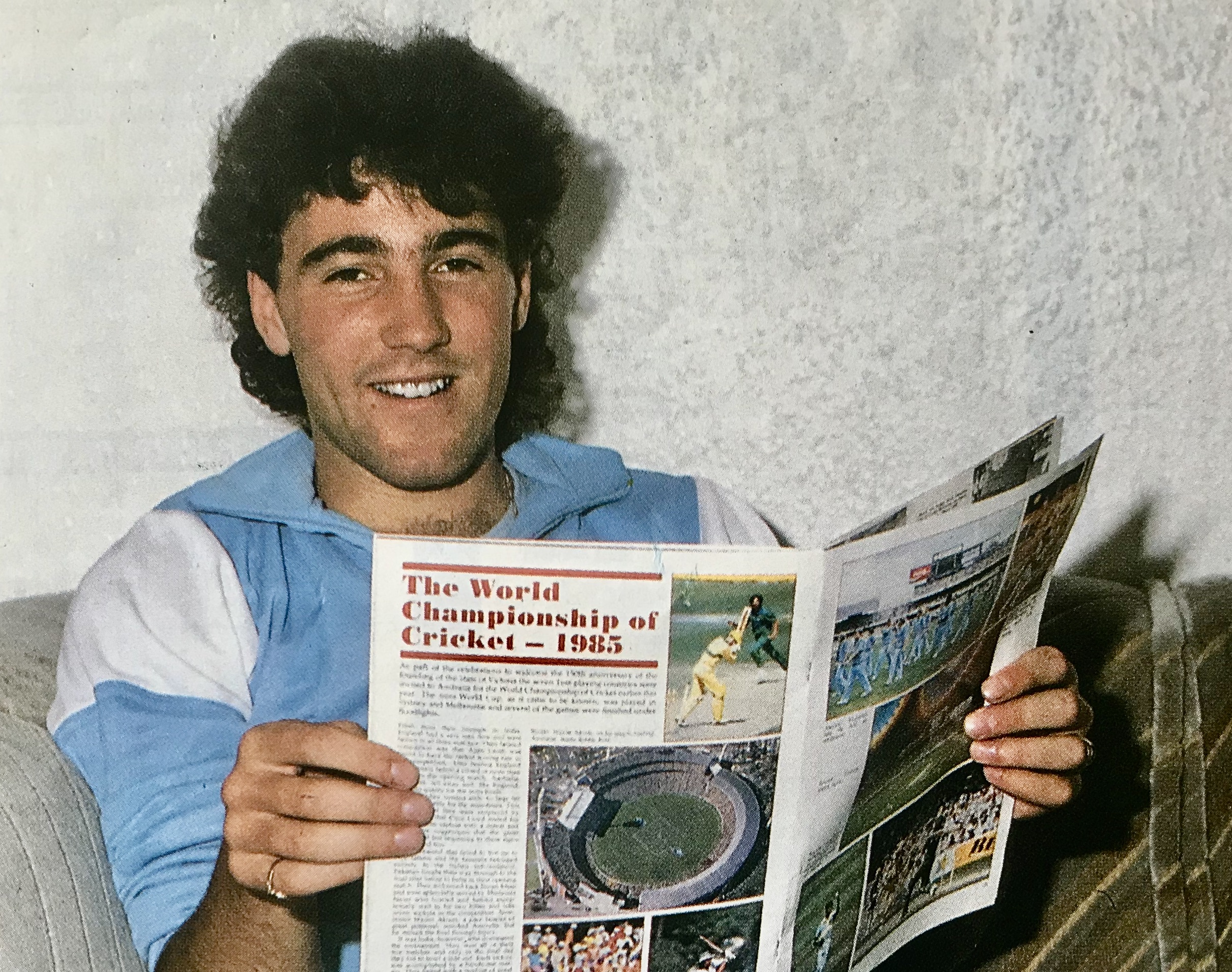

Shoot! magazine previewed Ruggiero’s eager anticipation at returning to the Victoria Ground for a league game on 15 October but he was only a sub that day and, although he went on for fellow summer signing Eric Potts, Albion lost 1-0.

After only seven league and cup starts (and three appearances off the bench), Ruggiero then had to wait six months for another sub appearance.

He went on as a second half substitute for injured Paul Clark in a 1-0 win at Blackburn, combining with Potts who went on to score the only goal of a game described by Argus writer John Vinicombe as “the most exhilarating match I have seen for years”.

Ruggiero didn’t make another start until the very last game of the season; but what a match to play in. A crowd of 33,431 packed in to the Goldstone to see the Seagulls take on Blackpool, with another possible promotion finely poised.

Albion dutifully won the game 2-1 (sending Blackpool down) with goals from Brian Horton and Peter Ward but their hopes of going up were cruelly dashed when Southampton and Spurs, who each only needed a draw to go up, lo and behold ground out a 0-0 draw playing each other.

As the Argus reported: “When news came of the goalless draw at The Dell there were cries of ‘fix’ and Albion had to suffer the bitter disappointment of missing promotion by the difference of nine goals.”

Before his recall for that clash, Ruggiero had continued to find the back of the net for the reserves – indeed he was the side’s top scorer for two seasons.

The Albion matchday programme reported his scoring exploits in some detail. For instance, in a 4-1 win away to Portsmouth. “John Ruggiero was the star of our win at Fratton Park with two fine goals and might have scored a hat-trick,” it said.

And in a 5-2 Goldstone win over Charlton Athletic, Ruggiero opened the scoring with a header from a Gary Williams cross, Steve Gritt pulled one back for the Addicks and Ruggiero volleyed in a fourth goal from the edge of the box.

Ruggiero, who lived in Shoreham with his wife Mary, discovered competition for a first team spot intensified after his summer signing: Clark from Southend adding steel to the midfield and Fulham’s Teddy Maybank taking over from Ian Mellor as Ward’s striking partner. O’Sullivan, meanwhile, comfortably stepped up to the higher level and kept his place.

When Albion were on course for promotion to the elite the following season, Ruggiero’s first team involvement was almost non-existent (a non-playing sub on one occasion).

He was sent out on loan to Portsmouth, then in the old Division 3, where he was a teammate of Steve Foster. Ruggiero scored once in six appearances, netting in a home 2-2 draw with Cambridge United on 27 December 1977.

He was released before Albion took their place amongst the elite and moved on to Chester City, signed by player-manager Alan Oakes, the former Manchester City stalwart.

Ruggiero joined just as ex-Albion teammate Mellor was moving on from Sealand Road, but, in a Chester team photo (above right), Ruggiero is standing alongside Jim Walker, who’d played at the Albion under Peter Taylor, and in the front row is a young Ian Rush.

Ruggiero scored within three minutes of his first league game for Chester, setting them on their way to a 3-2 win over Chesterfield. But he only made 15 appearances for them before dropping into the non-league scene.

The legendary England World Cup winner Gordon Banks, formerly of Stoke, signed Ruggiero for Telford United in the 1979-80 season when he was briefly manager of the Alliance Premier League side.

Born in Blurton on 26 November 1954 to Italian parents, the young Ruggiero went to Bentilee Junior School then Willfield High School. His prowess on the football field saw him represent Stoke Boys and the county Staffordshire Boys side and he was one of 24 young players who had a trial at Middlesbrough for the England Schoolboys side but missed the final cut.

He had the chance to join Stoke City at 15 but stayed on at school and passed five O levels: English Language, English Literature, Technical Drawing, History and Art.

“I had a lot of interest from many clubs: Blackpool, Leicester City, Derby County, Blackburn Rovers, Bolton Wanderers, Coventry City, West Brom and I even had a letter from Arsenal inviting me to go training with them,” Ruggiero told Nicholas Lloyd-Pugh for the svenskafans.com website in an April 2011 interview.

“I nearly signed for Coventry but the very last club to ask me was Stoke City and, once this happened, I knew where I would go. I joined as an apprentice when I was 16 in 1970.”

Ruggiero explained how he started in the A youth team, progressed to the reserve side and finally made his first team debut under Tony Waddington on 5 February 1977, in a home 2-0 defeat against league leaders Manchester City.

He had made his league debut the previous season during a short loan period with Workington Town, playing three games in Division Four, which gives him the relatively rare distinction of having played in all four divisions of English football.

Even as a reserve team regular at Stoke he got to play at big stadiums like Old Trafford, Anfield, Elland Road, Hillsborough and Goodison Park. “It was great for the young players but you always hoped to make the first team at some point,” he said.

“It was a real dream for me to have players like Gordon Banks, Geoff Hurst, Alan Hudson, Peter Shilton and many more being part of your life.

“Tony Waddington loved his team and he always went for experience, so the younger players found it really hard to make the first team. However, a few younger players did well such as Alan Dodd, Sean Haslegrave, Stewart Jump, Ian Moores and Garth Crooks.”

He continued: “Players like Terry Conroy and John Mahoney were really friendly and always had a word of advice for you. I really liked Alan Dodd; he was a much underrated player and would have played for England at a bigger club.”

Ruggiero also spoke warmly of Alan A’Court, Stoke’s first team coach who had played for Liverpool, who took him on a football holiday to Zambia in 1973 where he played for Ndola United. A’Court was Zambia’s national coach at the time.

Two years later, Ruggiero earned a ‘Player of the Tournament’ accolade while playing for Stoke in a youth tournament in Holland.

Waddington’s successor as manager, former player George Eastham, also played a part in Ruggiero’s development by arranging for him to play in South Africa for eight months in 1975 where he was a league and cup winner with Cape Town City.

“I knew that George liked me as a player so I felt that this could be good for me when he took over the team,” Ruggiero told Lloyd-Pugh. “He had already played me in a friendly match against Stockport which was a showcase for the return of George Best from America.

“Whilst Best, Hudson and Greenhoff were doing their party tricks, I was quietly having a good game and it was clear that I was ready for another chance.”

That came in a home game against Liverpool, Ruggiero playing in midfield. “The next 90 minutes was my best of all time,” he said. “We drew the game 0–0. I would like to think I was the man of the match and George spoke very highly of me to the press after the game. The Liverpool team included Kevin Keegan, Ray Kennedy, Ray Clemence and many other big names.”

Stoke had turned to youngsters like Ruggiero because big name players had been sold off to pay for a replacement Butler Street stand roof at the Victoria Ground.

And while the youngster kept his place after that impressive display v Liverpool, they only won one of their remaining nine games and were relegated. It was little consolation that he scored twice away to Coventry because they lost 5-2.

“After the Liverpool game I was on a high, I really thought I’d made the big time and would be a first team player at Stoke for years to come,” he said. “I played nearly all the games left that season and was pretty consistent in all of the games.

“I was just enjoying my time and never really thought about relegation.”

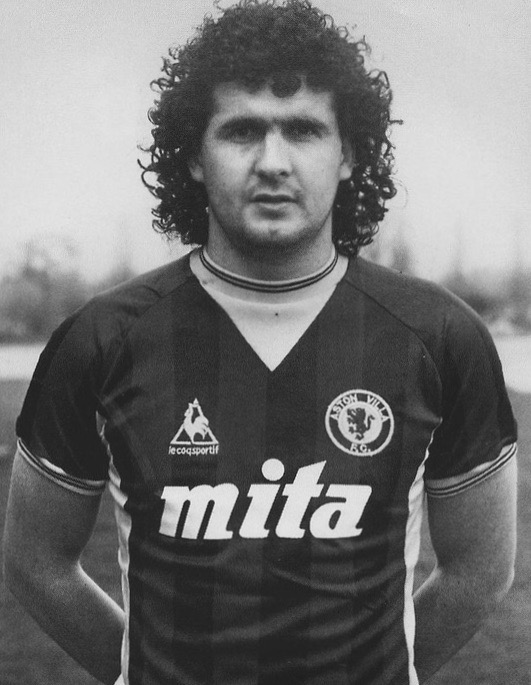

But the 1-0 last day defeat at Aston Villa would prove to be his last game for Stoke because Brighton, who had gained promotion from the third tier, were bolstering their squad to compete at the higher level.

Ruggiero signed for the Seagulls along with Lawrenson and Williams, who moved from Preston (swapping places with Graham Cross and Harry Wilson), and Sheffield Wednesday winger Potts.

While Lawrenson was on the path to greatness, and Williams established himself in Albion’s left-back spot, Potts found his involvement was mainly from the bench and Ruggiero’s early promise faded.

After his short football career was over, Ruggiero joined the police, serving in the Cheshire force, rising to the rank of detective sergeant and mainly working in the Crewe area.

When the Goldstone Wrap blog checked on him in 2014, they unearthed a Facebook message in which he said: “Loved my short time in Brighton. Would have liked to have played a few more games but still love the place and the team were buzzing at that time.”

And in 2020, a former police colleague, Steve Beddows, informed the Where Are They Now website that Ruggiero had retired and was continuing to live in the Stoke area.

“He remains a very fit man with a keen eye for precise action posed wildlife photography and undertakes huge amounts of charitable work,” said Beddows. “A great sense of humour but very dogged, smart and highly professional. He does masses for charity with Stoke City Old Boys Association still and had the nickname ‘Italian Stallion’ because of his good looks.

“I never heard a bad word about him from anyone and he can still run marathons and plays lots of golf.”

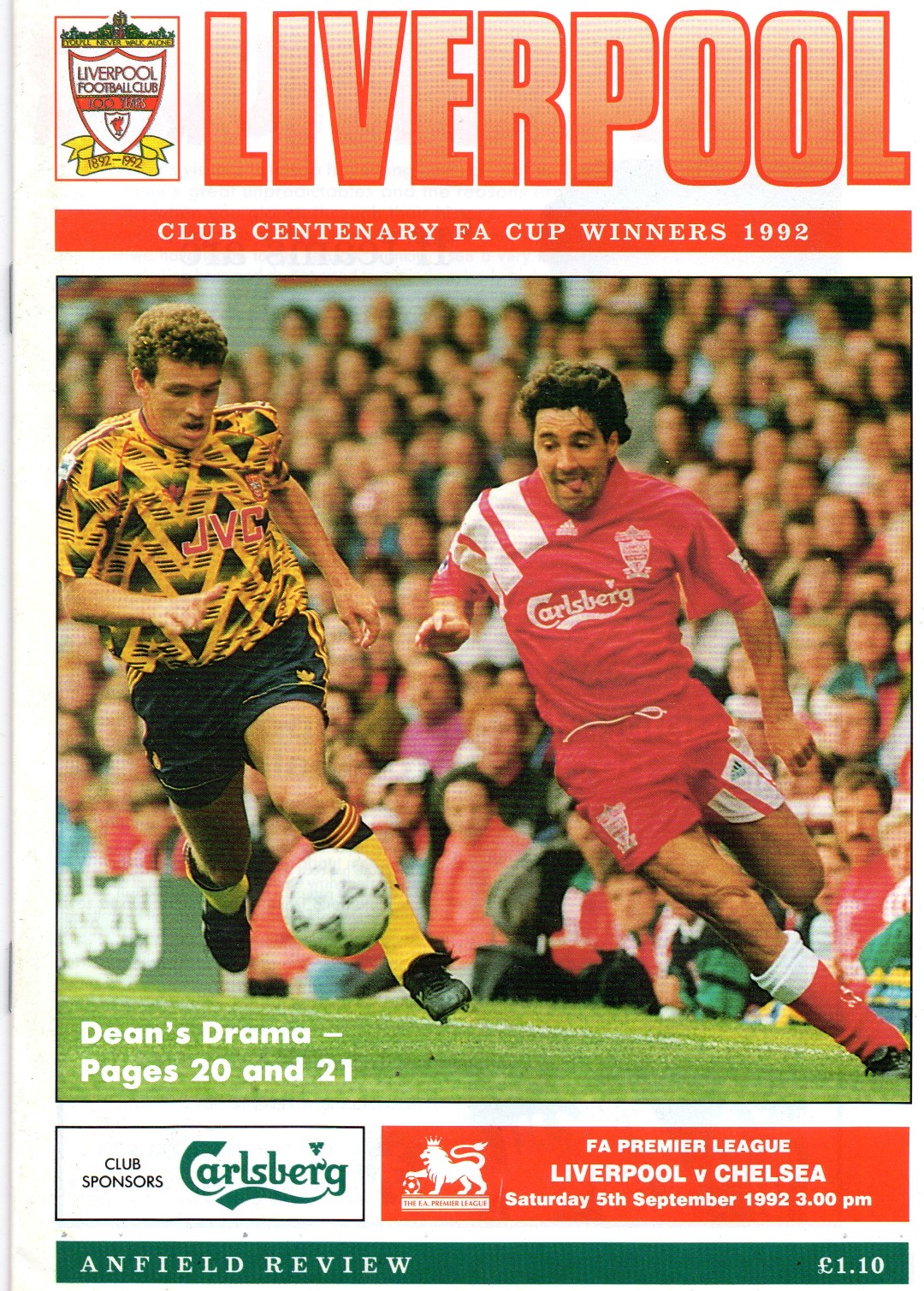

Perhaps it was surprising, though, that champions Liverpool were the ones to snap him up, particularly as Ian Rush and Kenny Dalglish were in tandem as first choice strikers.

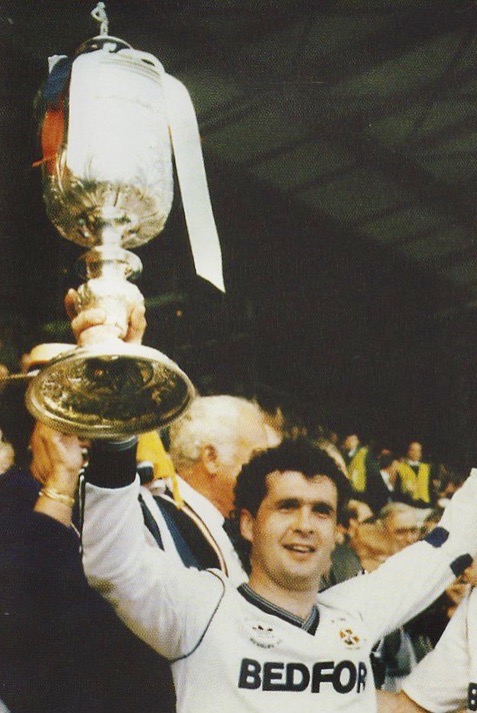

Perhaps it was surprising, though, that champions Liverpool were the ones to snap him up, particularly as Ian Rush and Kenny Dalglish were in tandem as first choice strikers. Nevertheless, asked many years later to describe his proudest moment in football, he maintained: “Scoring the winning goal in the FA Cup semi-final that meant that a bunch of mates at Brighton were going to Wembley in 1983.”

Nevertheless, asked many years later to describe his proudest moment in football, he maintained: “Scoring the winning goal in the FA Cup semi-final that meant that a bunch of mates at Brighton were going to Wembley in 1983.”

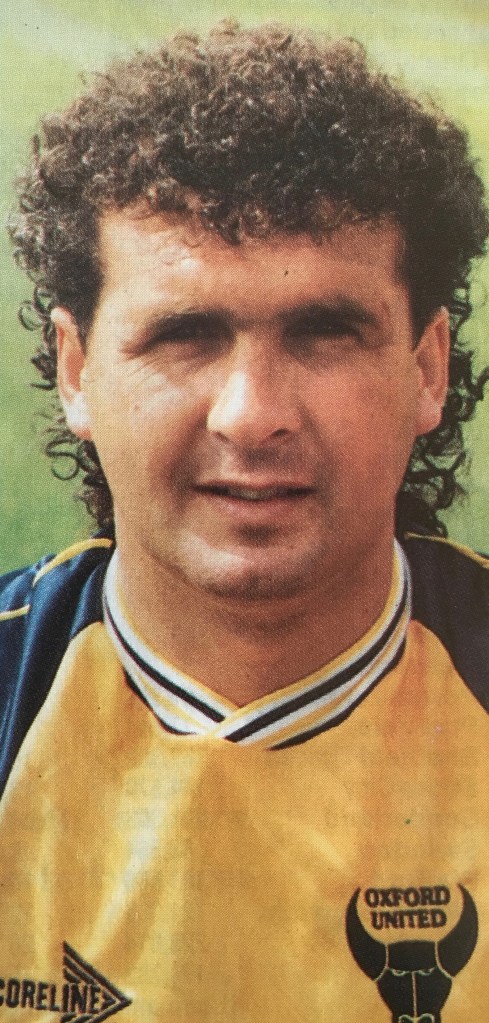

He had yet more Wembley heartache during a two-year spell with Queen’s Park Rangers, being part of their losing line-up in the 3-0 league cup defeat to Oxford United in 1986.

He had yet more Wembley heartache during a two-year spell with Queen’s Park Rangers, being part of their losing line-up in the 3-0 league cup defeat to Oxford United in 1986.