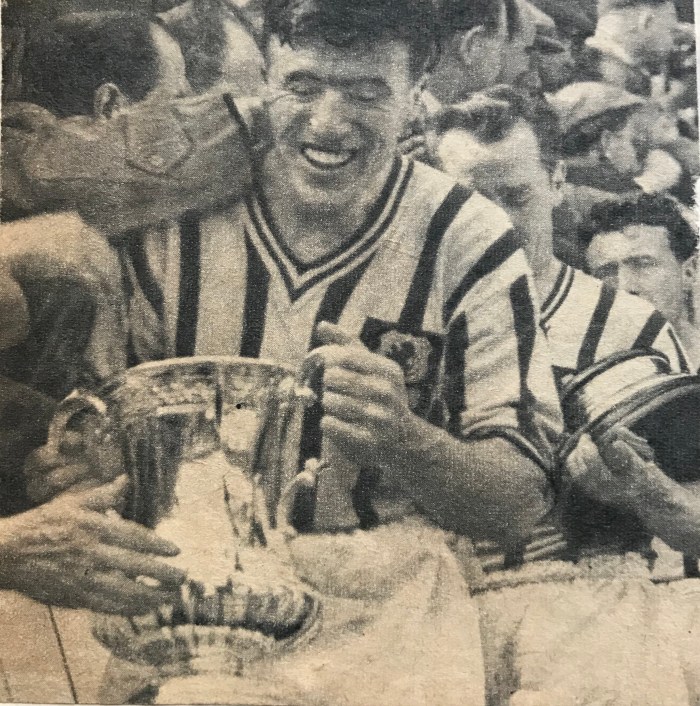

A FORMER Aston Villa captain and 1957 FA Cup winner steered Brighton to the first promotion I witnessed on my Albion journey.

Genial Irishman Pat Saward, who lived in my hometown of Shoreham during his time as Albion boss, galvanised a squad not expected to be promoted from the third tier and took them up as runners up behind his former club in 1972.

As the champagne flowed in the Goldstone Ground home dressing room, Saward took centre stage surrounded by his blue and white stripe-shirted heroes.

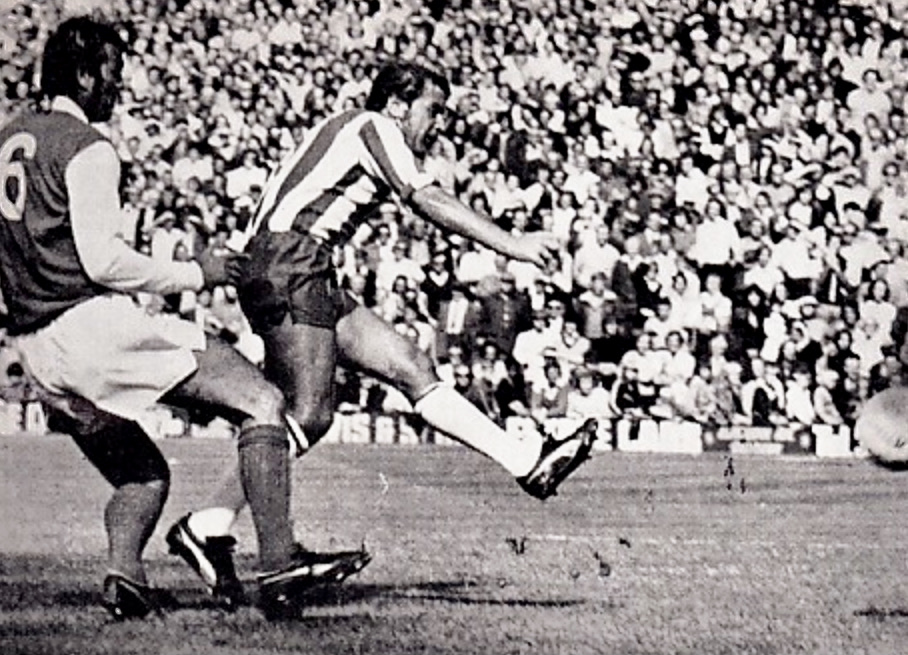

When the promotion tilt had looked like faltering, he’d been bold enough to make drastic changes to the side before a top of the table clash with Villa in front of the Match of the Day cameras. After a memorable 2-1 win in which Willie Irvine scored a goal later judged as the third best in the programme’s Goal of the Season competition, Saward added to his squad on transfer deadline day, bringing in Northern Ireland international Bertie Lutton from Wolves and Ken Beamish from Tranmere Rovers, described in the Official Football League Book as “stocky and packed full of explosive sprinting power, a terrific shot and great appetite for the game”.

Saward told the publication: “They were both last ditch signings and Ken made an astonishing difference. I spent only £41,000 in getting my promotion side together so we were very much Villa’s poor relations in that sense.”

The manager put the success down to: “Dogged determination to succeed from all the players. We stamped out inconsistency. I got rid of ten of the players I inherited and got together a team built on character. That’s the key quality, apart from skill of course.”

However, hindsight reveals the club wasn’t really ready for the higher division and some have suggested Saward broke up the promotion-winning squad rather too hastily. Players he brought in who were used to the level now known as the Championship struggled to gel, and the manager turned to rather too many loan signings.

A mid-season run of 13 consecutive defeats was Albion’s undoing and a glamour FA Cup tie at home to First Division Chelsea in early January 1973 gave a welcome respite from the gloom.

Ahead of the match, Saward opened his heart to Daily Mirror reporter Nigel Clarke, revealing that he couldn’t understand why the side had struggled so much.

“I wish I knew. But I’ve learned more about football these last few weeks than at any other time in my career.

“We are five points behind the next club but I must be the luckiest man in the league. There are no pressures on me,” he said, explaining that supporters were still writing to him, backing him and the team.

“When we came up from the Third Division, I was so big-headed, so confident. I thought with the right results we could go straight through to the First Division. I really did.

“There was spirit and ambition here – and there still is….that’s how this club gets you. My heart is in the place.”

Saward revealed that he had turned down two better paid jobs in the First Division to stay at Brighton after the promotion win, telling Clarke: “What I want is importance, appreciation, understanding and love…not being kicked up the backside and put under the lash.

“Adulation is false. I’ve found my oasis at Brighton and I’m wealthy the way I want to be – in feeling.”

Although the Chelsea game ended in another defeat, fortunes eventually changed the following month – but the damage had been done and Brighton went straight back down.

A defiant Saward promised to blood more youngsters like Steve Piper and Tony Towner, who’d done well when drafted in and Piper, in a matchday programme article, said of him: “Saward was more of a coach than a man-manager, very suave and sophisticated. He knew his football from his days at Coventry.”

However, when results didn’t improve on the return to third tier level, and with a new, ambitious chairman – Mike Bamber – at the helm, Saward was sacked and replaced with the legendary Brian Clough.

Albion’s hierarchy had turned to the untried Saward in the World Cup summer of 1970 after Birmingham City poached Freddie Goodwin from Brighton to replace Stan Cullis as their manager. It was second time lucky for Saward, who’d applied to succeed Archie Macaulay two years previously when Goodwin pipped him to the post.

“Give me ten years and I’ll have Brighton in the First Division,” Saward declared when appointed. Prescient words considering they made it within nine – although it came six years after he’d parted ways with the club.

There’s little doubt Saward was an innovative football man and a popular figure during the first two years of his reign.

Apart from success on the pitch in the 1971-72 season, the way he involved fans in helping him to improve the side also proved a winner.

His buy-a-player appeal was a direct attempt to involve the supporters in the affairs of their club and Saward led a sponsored walk on Brighton seafront as one of the initial events geared towards generating funds to help him compete in the transfer market.

“Too many people spend too much time shouting about how hard up their club is, and too little time fighting to improve the situation,” Saward said in an article for the April 1971 edition of Football League Review. “You never get success if you sit around. You must have courage, even audacity, and work hard for survival.”

The first funds generated provided Saward with the money to bring in experienced Bert Murray from Birmingham City, initially on loan, and then permanently. Murray would go on to be voted Player of the Year in 1971-72.

Another player who signed on loan at the same time as Murray was Preston’s Irvine, who recalled in his autobiography, Together Again, how Saward wooed him.

“Pat sold me the place with his charm and persuasive ways,” he said, describing the former male model as “extrovert, infectious and bubbly”.

He added: “Pat Saward was a gem of a manager and a pleasure to play for. He said what he thought, but never offensively; in a matter-of-fact, plain-speaking kind of way, rather than aggressively.”

Irvine continued: “Saward had the knack of making people feel important. He instilled pride and a sense of identity…..Pat loved attacking, entertaining football and worked tirelessly for the club. I would have run through that proverbial brick wall for him.”

As Brighton neared promotion, Irvine said: “Saward, with a joke or a smile, an arm around the shoulder or a bit of geeing up, knew just how to keep a dressing room happy or dispel any tension or nerves.”

Sadly, Irvine’s opinion of Saward shifted dramatically when, during the summer, the manager told him he intended to bring in a replacement – although it was three months before he eventually signed Barry Bridges from Millwall.

Irvine was in the starting line-up at the beginning of the season and scored six times in 13 league and cup games, but, once Bridges arrived in October, his days were numbered, and, before the year was out, he was sold to Halifax Town in part exchange for Lammie Robertson.

Saward had already dispensed with the services of Albion’s other main promotion season scorer, Kit Napier, along with his former captain, John Napier.

Irvine said that once Albion were promoted, Saward changed. “He seemed to become unapproachable, or at least he did to me, and where once I could see him whenever I wanted, now I seemed to have to book an appointment two or three days in advance. We all had to.”

Teammate Peter O’Sullivan, who had repaired his relationship with Saward after some difficult early exchanges which saw the Welshman transfer-listed, also witnessed a change in the manager.

“We had one or two players who were over the hill and Pat just lost the plot. It was grim,” he told Spencer Vignes in A Few Good Men.

Albion’s tier two fortunes were picked over in some detail in a feature reporter Nick Harling compiled for Goal magazine.

“I didn’t foresee the snags and the type of league the Second Division was,” Saward told him. “It’s the hardest division of the four. Everyone is fighting either to stay in or get out.

“It’s a hell of a hard division. It’s a mixture of the First and Third. It’s good and very hard football. They don’t give you an awful lot of time to play.

“It’s a division governed by fear because to drop out of it is not good, while to get out at the top is fantastic. I didn’t believe the gap would be so different.

“Teams are so well organised and supplement their lack of ability with tremendous defensive play. It’s very hard to get results.”

While open and honest, they didn’t sound like the words of a manager very confident of finding a solution, and Saward sought to explain part of the problem when he said: “To me the most important thing is the attitude of mind. Players should have an arrogant attitude, an attitude that they’re going to do well even when the chips are down. But some types are destroyed. These are the ones who succumb and want to rely on other people.

“Here we’ve got some great boys, but I wish to God some of them had more determination.”

Bamber was resigned to relegation but nonetheless confident of where the club was heading. “There’s no doubting it – First Division here we come,” he told the magazine.

Saward added: “I haven’t lost any enthusiasm. I’ve had my hopes dampened slightly, but one overcomes that.

“This club has got to be built for the future. I want to put Brighton on the map.”

Sadly, when Albion’s poor form at the start of the 1973-74 season continued, Saward publicly admitted: “I haven’t any more answers. I am in a fog.”

Unsurprisingly, the Albion’s directors interpreted it as a loss of confidence and sacked him.

Saward never managed in the English game again, although he coached in Saudi Arabia for a while.

Born in Cobh, County Cork, on 17 August 1928, Saward lived in Singapore and Malta during his childhood, before the family moved to south London.

His first club was Beckenham FC before he turned professional with Millwall in 1951. He made 118 appearances for the Lions in the next four years.

Saward was 26 when Eric Houghton signed him for Villa for £7,000 in August 1955. The legendary Joe Mercer took over as Villa manager in 1958.

Pat enjoyed a goalscoring debut with his new club, hitting the final equalising goal in a 4-4 draw with Manchester United at Villa Park on 15 October 1955. But he struggled to oust left half Vic Crowe and made only six appearances that season.

In Crowe’s absence through injury the following season, Saward became a regular, making 50 appearances.

In total, Saward played 170 games for Villa between 1955 and 1960, most notably featuring in their FA Cup winning team in 1957. Villa beat Manchester United 2-1 in the final at Wembley Stadium in front of a crowd of 99,225, Peter McParland scoring twice to win Villa the Cup for a seventh time.

Saward made only 14 appearances as Villa were relegated from the top-flight in 1959 but he was back in harness as captain when they made a swift return as Second Division champions in the 1959-60 season.

In his final season, he made just 12 appearances, his last coming on 22 October 1960 in a second city derby, Villa beating Birmingham 6-2. The following March, he was given a free transfer and moved on to Huddersfield Town.

He had first been selected for the Republic of Ireland on 7 March 1954 in a World Cup qualifier in which Luxembourg were beaten 1-0, and he went on to make 18 appearances for his country, the last, on 2 September 1962, coming when he was 34: a 1-1 draw away to Iceland in Reykjavík.

He played twice against England in World Cup qualifiers in 1957, a 1-1 draw and a 5-1 defeat, when he was up against the likes of Duncan Edwards, Johnny Haynes and Stanley Matthews, and in the same competition against Scotland, in 1961, when the Irish lost 4-1, and his teammates included Johnny Giles.

After 59 appearances for the Terriers, he dropped out of the league but acquainted himself with Sussex when moving to Crawley Town.

Jimmy Hill signed him for Coventry as a player-coach in October 1963 and although he made numerous reserve team appearances, he really made his mark as a coach and was responsible for the rapid development of City’s youth team in the 1960s.

Willie Carr and Dennis Mortimer were just two of several first teamers who made it under his guidance. He stepped up to first team assistant manager when his former Eire teammate, Noel Cantwell, was appointed boss in 1967.

Not long after his switch to the Goldstone, Saward picked up one of his former Sky Blues proteges, Ian Goodwin, initially on loan, and then permanently, and eventually made him Albion captain. The rugged defender’s arrival was remembered in an Argus article.

When Saward died on 20 September 2002 following a period when he’d suffered with Alzheimer’s, an excellent Villa website pieced together a detailed obituary. His career is also recorded on the avfchistory.co.uk site.

Saward was laid to rest in the same Cambridge cemetery as his brother Len, a forward who played a total of 170 games for Cambridge United between 1952 and 1958, scoring 43 times. He went on to serve the club behind the scenes in their commercial department.

Pictures from my schoolboy Albion scrapbook and various online sources.

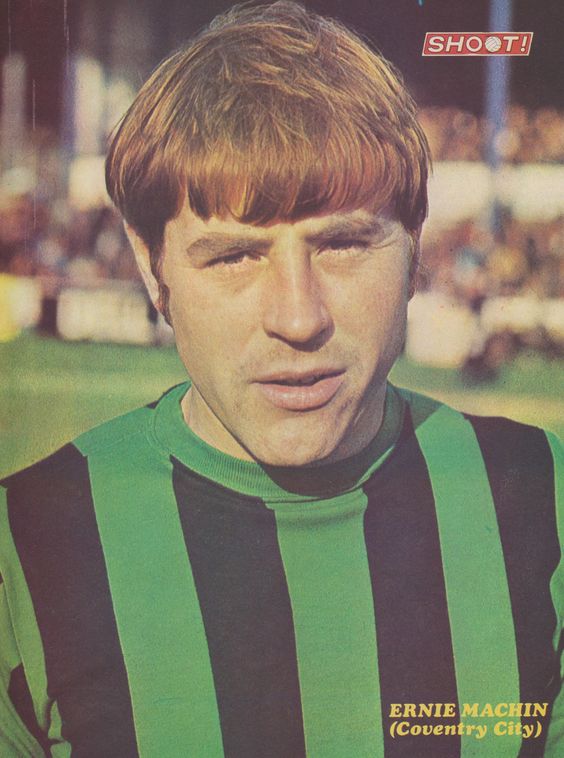

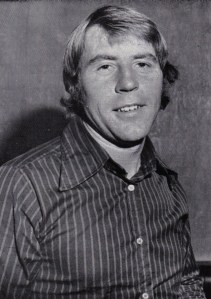

A MIDFIELD dynamo who captained Coventry City during their glory years at the top of English football’s pyramid was instantly installed as captain when he signed for third tier Brighton.

A MIDFIELD dynamo who captained Coventry City during their glory years at the top of English football’s pyramid was instantly installed as captain when he signed for third tier Brighton. The midfielder eventually completed 31 games (plus three as sub) but manager Taylor took the captaincy from him and appointed his new centre back signing,

The midfielder eventually completed 31 games (plus three as sub) but manager Taylor took the captaincy from him and appointed his new centre back signing,  Machin played 41 games that season and only shared the midfield with Horton once – in what turned out to be his final game in the stripes, a 4-2 home win over Grimsby Town.

Machin played 41 games that season and only shared the midfield with Horton once – in what turned out to be his final game in the stripes, a 4-2 home win over Grimsby Town. Machin was a member of the Coventry City Former Players Association after his career ended and they paid due respect to his part in the club’s history when he died aged 68 on 22 July 2012.

Machin was a member of the Coventry City Former Players Association after his career ended and they paid due respect to his part in the club’s history when he died aged 68 on 22 July 2012.

The following two years, he went to play in America for Memphis Rogues (pictured left) where his teammates were players from the English game winding down their careers: the likes of former Albion players

The following two years, he went to play in America for Memphis Rogues (pictured left) where his teammates were players from the English game winding down their careers: the likes of former Albion players

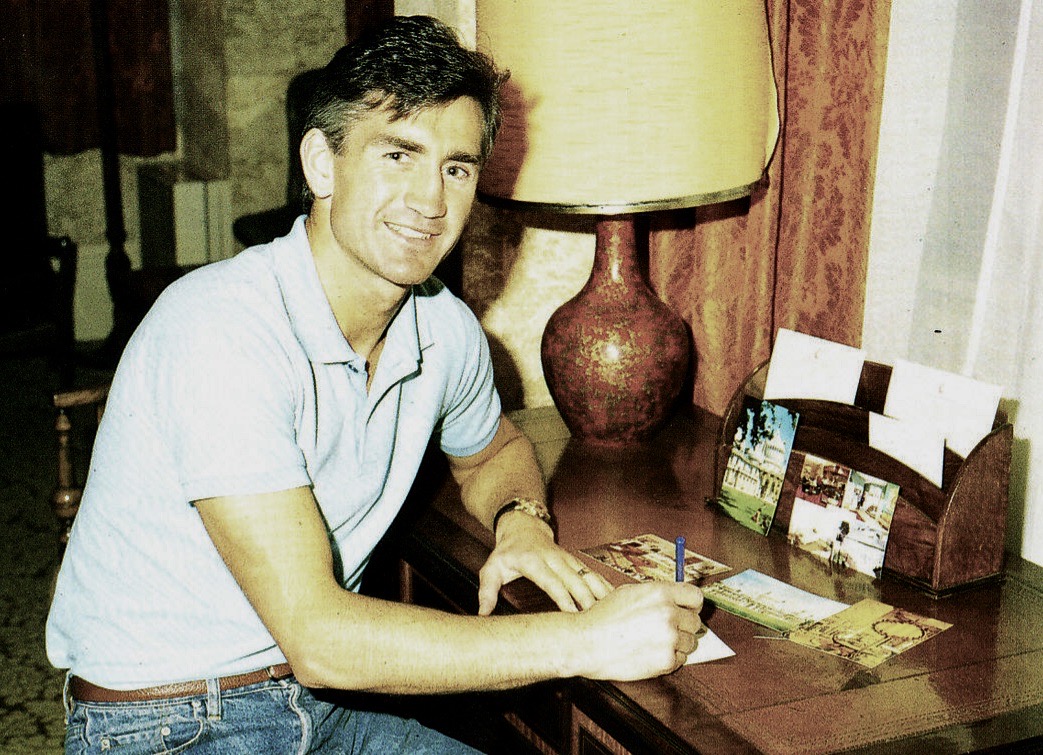

A CULTURED midfielder regarded in many circles as the best ever captain of Aston Villa was almost ever-present in one season with Brighton.

A CULTURED midfielder regarded in many circles as the best ever captain of Aston Villa was almost ever-present in one season with Brighton.

Knowing his time on the south coast was going to be limited, Mortimer didn’t uproot his family from their Lichfield home and instead lived in the Courtlands Hotel in Hove (above) for a while and also bought a flat where his wife and children could visit during school holidays.

Knowing his time on the south coast was going to be limited, Mortimer didn’t uproot his family from their Lichfield home and instead lived in the Courtlands Hotel in Hove (above) for a while and also bought a flat where his wife and children could visit during school holidays.

THE SONGS still sung today that immortalise

THE SONGS still sung today that immortalise