PACY DARREN HUGHES made his Everton first team debut two days after Christmas 1983 while still a member of the club’s youth team.

That game at Molineux ended in a 3-0 defeat for the young defender against bottom-of-the-table Wolves who had Tony Towner on the wing and John Humphrey at right-back.

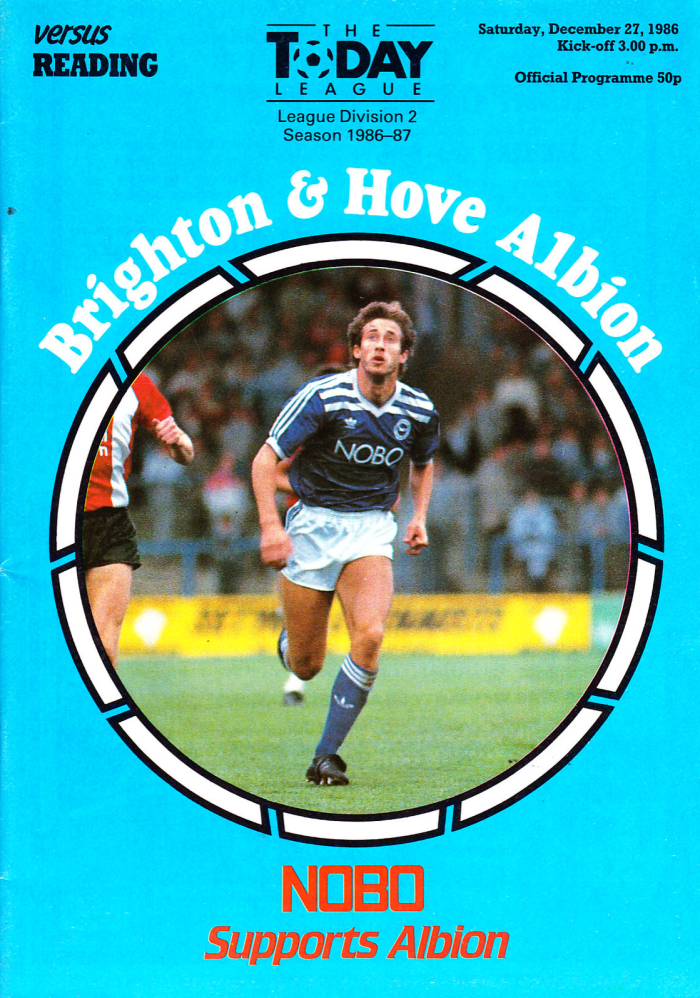

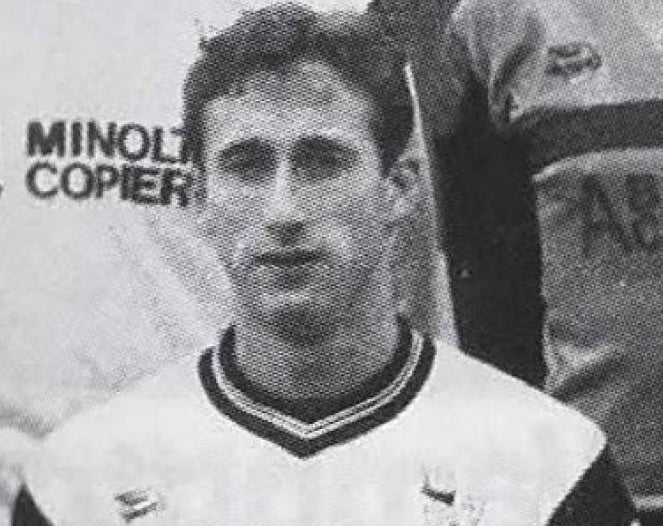

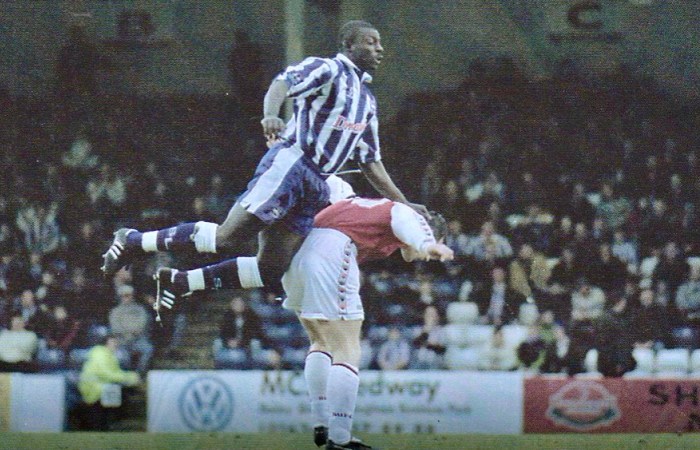

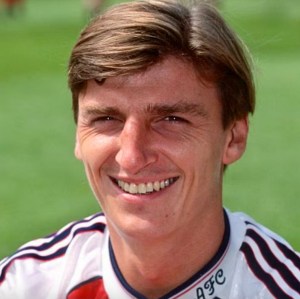

Exactly three years later, a picture of Hughes in full flight was on the front cover of Albion’s programme for their home festive fixture against Reading, the Scouser having signed for the second-tier Seagulls for £30,000.

The money to buy him came from the supporter-funded Lifeline scheme which also helped to buy goalkeeper John Keeley for £1,500 from non-league Chelmsford and striker Gary Rowell, from Middlesbrough.

Hughes had made only two more first team appearances for Everton before a free transfer move took him to second tier Shrewsbury Town, for whom he made 46 appearances.

It was while playing for the Shrews in a 1-0 win over Brighton that he had caught the eye of Alan Mullery, back in the Albion hotseat at the start of the 1986-87 season.

In his matchday programme notes, Mullery wrote: “Darren could become a really good player here. I was impressed with him when he played against us recently.

“He started at Everton and came through their youth scheme and had already played in their first team at 18. The grounding he received at Goodison should stand him in good stead.

“He has already shown he is the fastest player we have here, in training he even beat Dean Saunders in the sprints.”

Interviewed for the matchday programme, Hughes told interviewer Tony Norman: “I was quite happy at Shrewsbury. But when the manager told me Brighton were interested in signing me I thought it would be another step up the ladder. It’s a bigger club with better prospects and it’s a nice town as well.”

Hughes moved into digs in Hove run by Val and Dave Tillson where a few months later he was joined by Kevan Brown, another new signing, from Southampton.

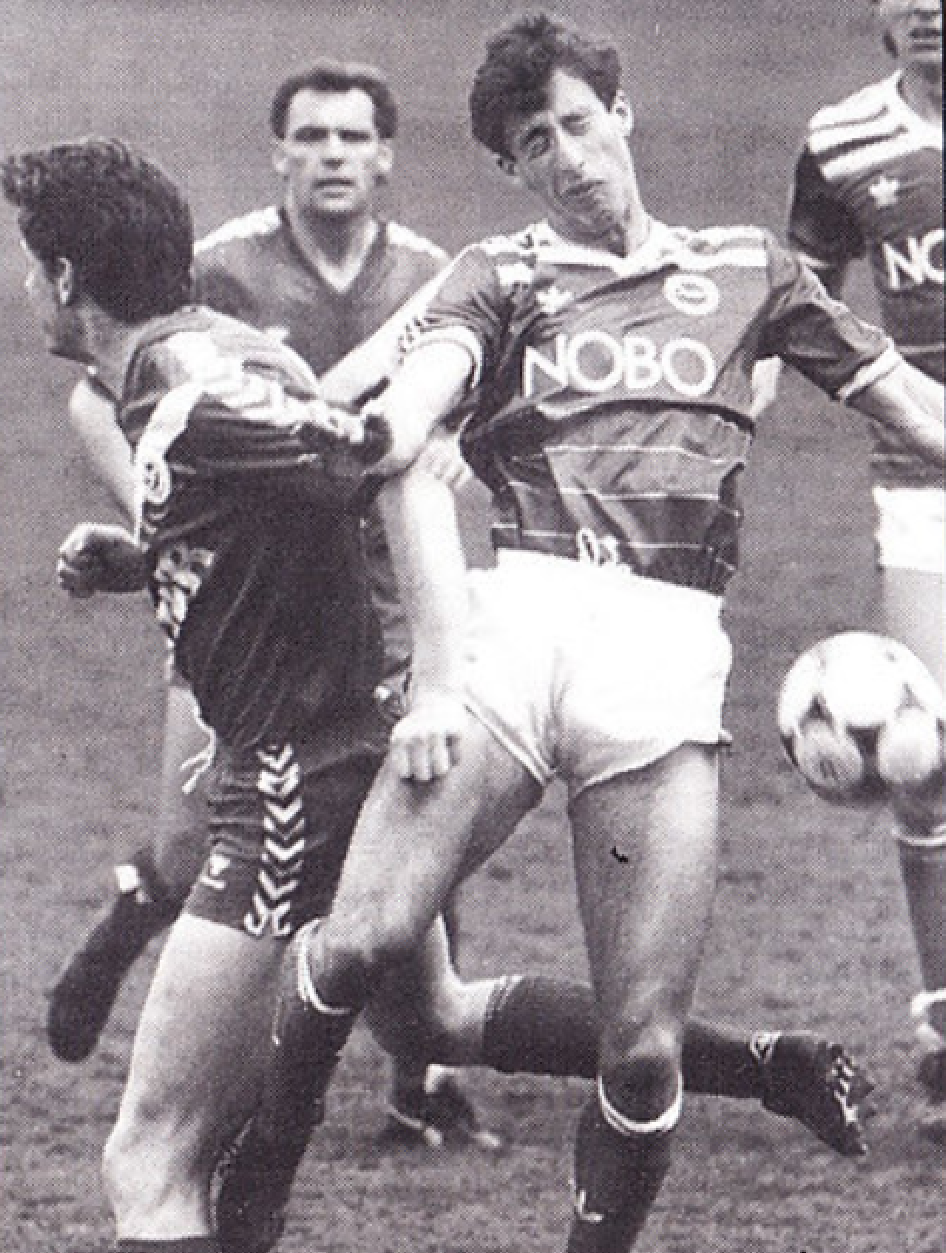

Hughes meanwhile had made his Albion debut in a 3-0 defeat at home to Birmingham in the Full Members Cup on 1 October 1986 and his first league match came in a 1—0 home win over Stoke City three days later courtesy of a Danny Wilson penalty.

He scored his first goal for the Seagulls in a 2-2 Goldstone draw against Bradford City as Mullery continued to see points slip away. With financial issues continuing to cloud hoped-for progress, 1987 had barely begun before Mullery’s services were dispensed with.

Hughes played 16 games under his successor Barry Lloyd but those games yielded only two wins and the Albion finished the season rock bottom of the division, dropping the Albion back into the third tier for the first time in 10 years.

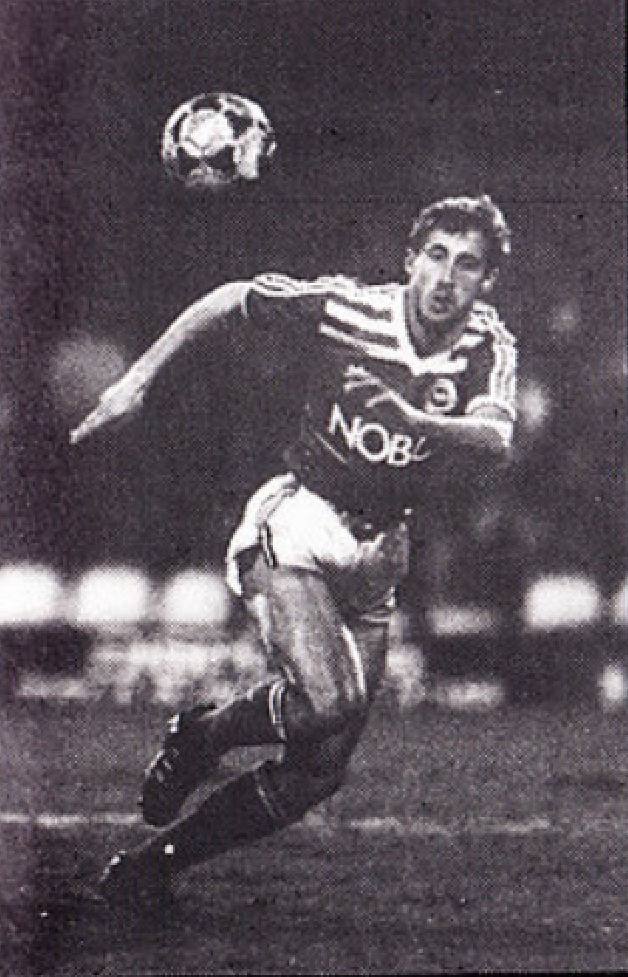

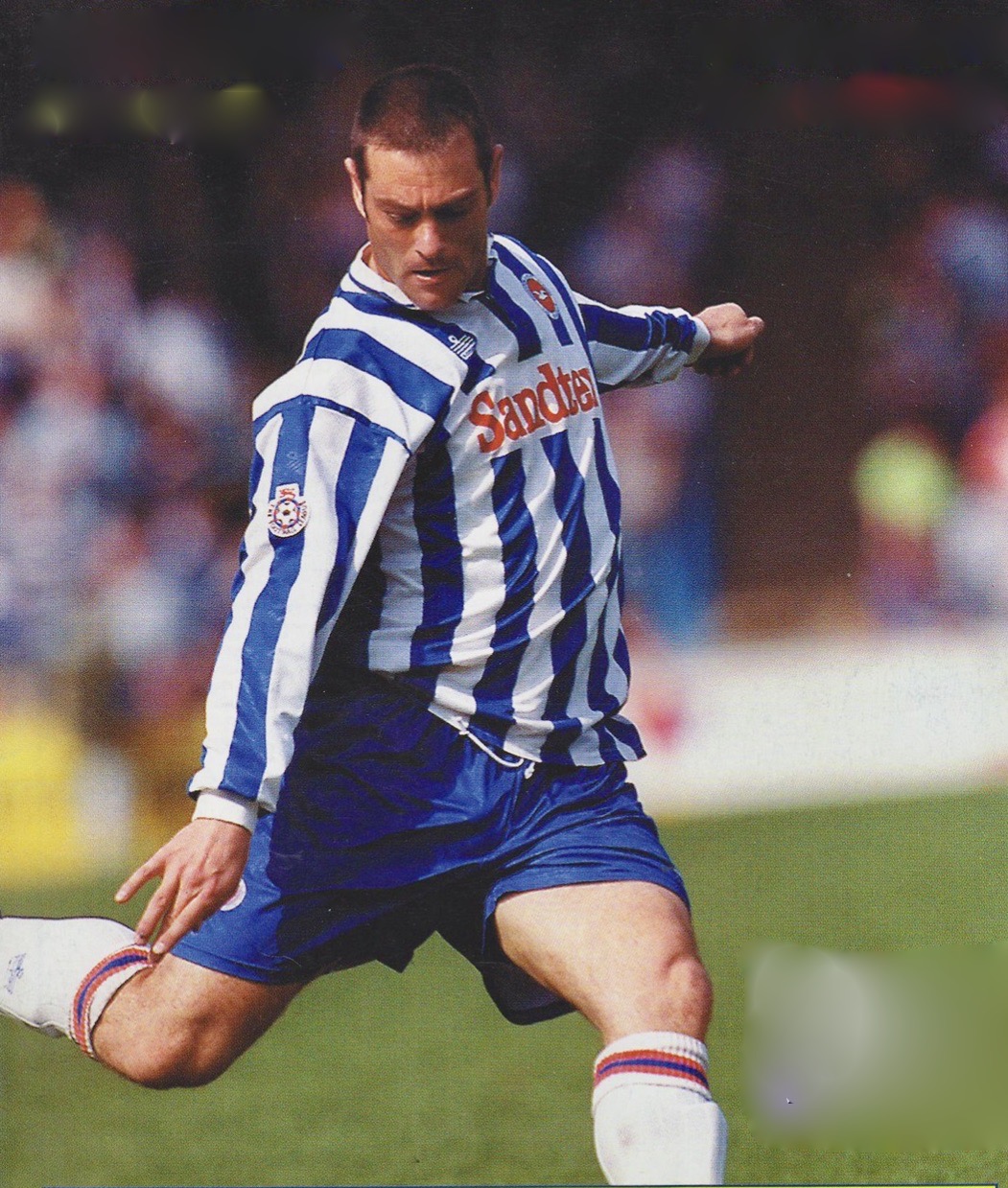

A rare happy moment during that spell was (pictured above) when Hughes slotted past George Wood in a 2-0 home win over Crystal Palace on Easter Monday although that game is remembered more for violent clashes between supporters outside the Goldstone Ground after fans left before the game had finished.

What turned out to be his 25th and final league appearance in a Seagulls shirt came in a 1-0 home defeat to Leeds when he was subbed off in favour of youngster David Gipp.

Hughes did start at left-back in a pre-season friendly against Arsenal at the Goldstone in early August (when a Charlie Nicholas hat-trick helped the Gunners to a 7-2 win) but when league action began he was on the outside looking in.

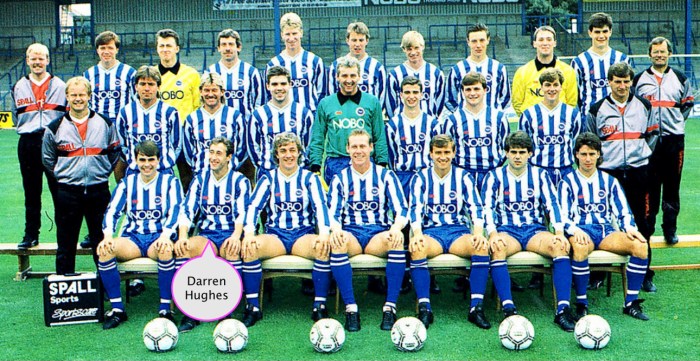

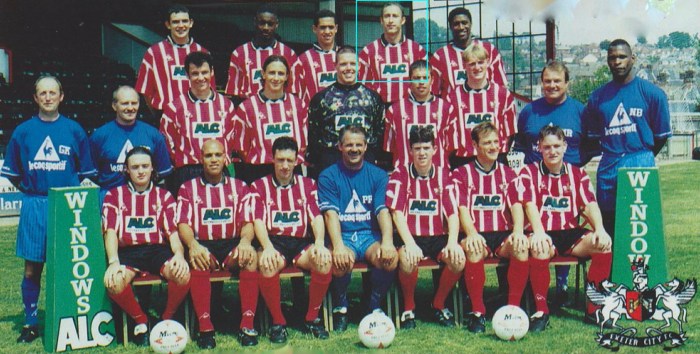

He was in the front row of the official team photo line-up for the start of the 1987-88 season, but Lloyd was building a new side with several new signings, such as Keith Dublin and Alan Curbishley, and young Ian Chapman was also beginning to stake a claim.

Hughes earned mentions in dispatches for his performances in the reserves’ defeats to Portsmouth and Spurs but come September he switched to fellow Third Division side Port Vale, initially on loan before making the move permanent.

Perhaps it was inevitable that when the Seagulls travelled to Vale Park on 28 September, Hughes was on the scoresheet, netting a second goal for the home side in the 84th minute to complete a 2-0 win.

Born less than 10 miles from Goodison Park, in Prescot, on 6 October 1965, Hughes went to Grange Comprehensive School in Runcorn and earned football representative honours playing for Runcorn and Cheshire Boys. He joined Everton as an apprentice in July 1982.

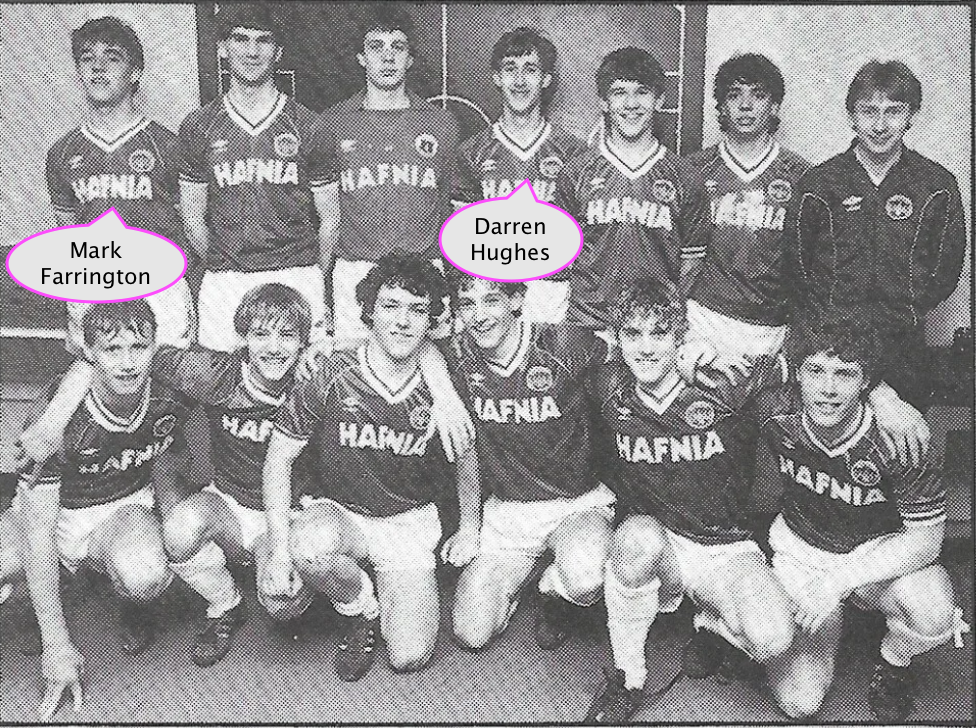

Originally a midfield player, he switched to left-back in the two-legged 1983 FA Youth Cup semi-final against Sheffield Wednesday (when Mark Farrington scored four in Everton’s 7-0 second leg win).

In the final against Norwich City, two-goal Farrington missed a late penalty in the first leg in front of an extraordinary 15,540 crowd at Goodison Park. The tie was drawn 5-5 but the Canaries edged it 1-0 in a replay to win the trophy for the first time.

If that was so near and yet so far, youth team coach Graham Smith saw his young charges make up for it the following year. Hughes was on the scoresheet as Everton won the FA Youth Cup for the first time in 19 years.

This is how the Liverpool Echo reported it: “Everton’s brave youngsters survived a terrific onslaught to take home the Youth Cup when beating Stoke City Youth 2-0 and winning by a 4-2 aggregate.

“And the man to set them on their way was 18-year old full-back Darren Hughes, who set the game alight in the 62nd minute with a brilliant goal.

“The Everton left-back picked the ball up on the halfway line and surged into the Stoke half before sending a wicked, bending drive past keeper Dawson.”

Eleven days later, there were even more Goodison celebrations when the first team won that season’s FA Cup, beating Watford 2-0 at Wembley.

Not long into the following season, Hughes learnt the hard way not to take anything for granted, as the website efcstatto.com revealed.

Manager Howard Kendall saw Everton Reserves, 2-0 up at half-time, concede six second half goals and lose 6-2 to Sheffield Wednesday Reserves.

He didn’t like the attitude he saw in several players and promptly put five of them, including Hughes, on the transfer list.

“It was important that we showed the players concerned how serious we were in our assessment of the game,” said Kendall. “Attitude in young players is so important. These lads would not be here if we did not think they have skill or we thought they would not have a chance of becoming First Division players.

“At some time, however, they must come to learn that football is not always a comfortable lifestyle. There are times when the only course of action is to roll up your sleeves and battle for yourself, your teammates and your club.”

Even though they were put on the transfer list, he said that they still had a future at the club as long as they behaved accordingly.

“What it does mean is that we shall be watching them very carefully over the next few months to see whether they have the right attitude in them – because it is a must,” said Kendall.

Hughes did knuckle down and at the end of what has come to be regarded as perhaps Everton’s greatest-ever season – they won the league (13 points clear of runners up Liverpool) and the European Cup Winners’ Cup (beating Rapid Vienna 3-1) and were runners up to Manchester United in the FA Cup (0-1) – he played two more first team games.

They were the penultimate and last matches of the season but were ‘dead rubbers’ because Everton had already won the league title and Kendall could afford to shuffle his pack to keep players fresh for the prestigious cup games that were played within four days of each other.

Hughes was in the Everton side humbled 4-1 at Coventry City, for whom Micky Adams opened the scoring (Cyrille Regis (2) and Terry Gibson also scored; Paul Wilkinson replying for Everton).

Two days later, he was again on the losing side when only two (Neville Southall and Pat Van Den Hauwe) of the team that faced Man Utd in the FA Cup Final were selected and the visitors succumbed 2-0 to a Luton Town who had Steve Foster at the back.

With the experienced John Bailey and Belgian-born Welsh international Van Den Hauwe in front of Hughes in the Everton pecking order, Kendall gave the youngster a free transfer at the end of the season.

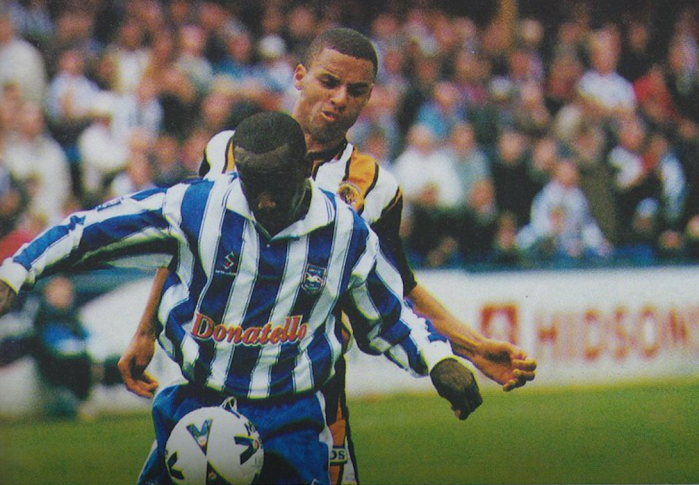

After he left Brighton, Hughes enjoyed some success at Vale, and according to onevalefan.co.uk formed one of the club’s best full-back partnerships together with right-back Simon Mills.

A highlight was being part of the side that earned promotion to the second tier in 1988-89, but his time with Vale was punctuated by two bad injuries – a hernia and a ruptured thigh muscle.

Vale released him in February 1994 but he initially took the club to a tribunal for unfair dismissal. He was subsequently given a six-week trial in August to prove his fitness and, upset with that treatment, he left the club in November 1994.

Between January and November 1995, he played 22 games for Third Division Northampton Town. He then moved to Exeter City, at the time managed by former goalkeeper Peter Fox, and made a total of 67 appearances before leaving the West Country club at the end of the 1996-97 season.

He ended his career in non-league football with Morecambe and Newcastle Town. After his playing days were over, according to Where Are They Now? he set up a construction business.

Six of his goals that season came in a run of four consecutive games between 27 November and 27 December, four of them penalties.

Six of his goals that season came in a run of four consecutive games between 27 November and 27 December, four of them penalties. In two years with the Bees, Mundee made 73 starts plus 25 appearances as a sub but, when his old Bournemouth teammate

In two years with the Bees, Mundee made 73 starts plus 25 appearances as a sub but, when his old Bournemouth teammate