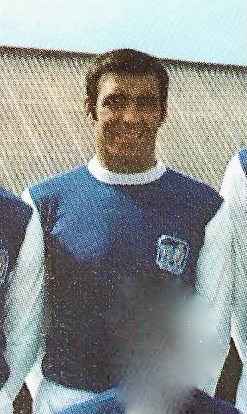

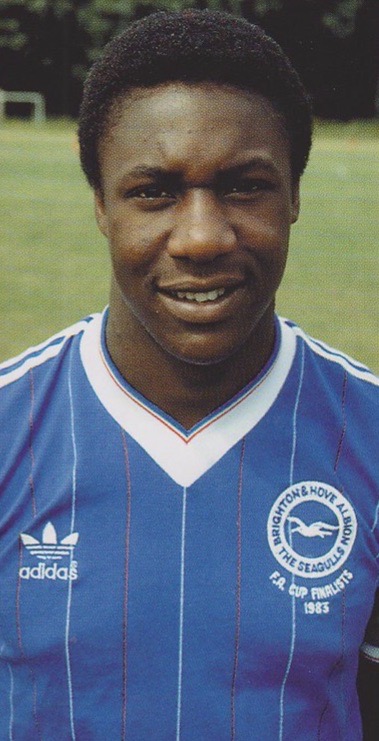

TERRY CONNOR is a familiar face to today’s football fans as a loyal assistant manager to Mick McCarthy.

TERRY CONNOR is a familiar face to today’s football fans as a loyal assistant manager to Mick McCarthy.

But Leeds United and Brighton fans of a certain vintage remember him as a pacy striker with an eye for goal.

His time with the Albion saw him at his most prolific with a record of almost a goal every three games (51 in 156 appearances) – form which earned him a solitary England under 21 cap as an over-age player.

Relegation-bound Brighton took the Leeds-born forward south in exchange for Andy Ritchie shortly after they had made it through to the semi-final of the 1983 FA Cup, but the new signing could take no part because he’d already played in the competition for Leeds.

If Brian Clough had allowed Peter Ward to have remained on loan to the Seagulls that spring, who knows whether Connor would have joined, but, when the former golden boy sought an extension of his loan from Nottingham Forest, which would have enabled him to continue to be part of the progress to Wembley, according to Ward in He Shot, He Scored, the eccentric Forest boss told him: ‘Son, I’ve never been to a Cup Final and neither will you’.

So the Connor-Ritchie swap went ahead and, with the rest of the team’s focus on the glory of the cup, the new arrival scored just the once in five appearances, plus two as sub, as the Seagulls forfeited the elite status they’d held for four seasons.

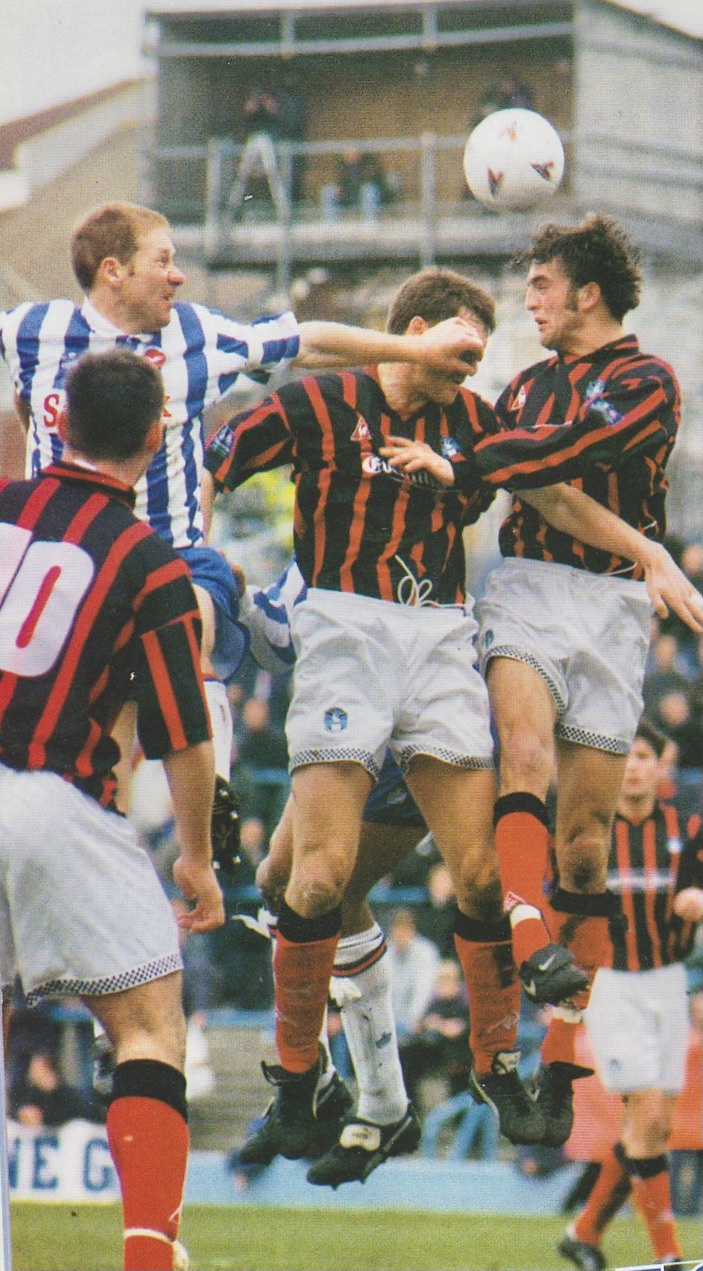

Connor would have his moment of cup glory (celebration above) in the following season, though, as the TV watching nation saw him and Gerry Ryan score in a 2-0 win over Liverpool at the Goldstone; the second successive season Albion had dumped the mighty Reds out of the FA Cup.

Connor would have his moment of cup glory (celebration above) in the following season, though, as the TV watching nation saw him and Gerry Ryan score in a 2-0 win over Liverpool at the Goldstone; the second successive season Albion had dumped the mighty Reds out of the FA Cup.

Born in Leeds on 9 November 1962, Connor went to Foxwood School on the Seacroft estate in Leeds. He burst onto the football scene at just 17, scoring the only goal of the game after going on as a sub for Paul Madeley to make his hometown club debut in November 1979 against West Brom.

“I got such an early break at Leeds because the club were rebuilding their side after those days when they were riding high,” Connor told Shoot! magazine. “Eddie Gray was still in the team when I came in. He was the model professional. It was terrific to have someone with his experience alongside you.”

Connor went on to make a total of 108 appearances for Leeds over four seasons, scoring 22 goals, before the by-then manager Gray did the swap deal with Ritchie.

In February 2016, voice-online.co.uk carried an interview in which Connor recalled racial abuse he received as a player.

“It was difficult for black players to thrive. I can remember going to many away games and there were bananas thrown on the pitch and `monkey’ chants from the stands,” he said.

“I remember receiving mail from Leeds fans telling me not to wear the white shirt, even though I was born and bred in Leeds. I had bullets sent to me and the police were called on a couple of occasions.”

Even so, the move to Brighton still came as a bit of a shock to him.

“‘I’d never imagined myself playing for anyone else but Leeds,” he told Shoot! at the time. “I was born and bred in the city. My parents and friends live there, and really Elland Road was a second home to me.”

Unfortunately for Connor, manager Jimmy Melia gave him the impression he was going to be forming a double spearhead with Michael Robinson. But after relegation, Robinson and several others from the halcyon days were sold, in Robinson’s case to Liverpool.

The man who bought him didn’t last long either; Melia making way for Chris Cattlin in the autumn of 1983. It didn’t stop Connor making his mark in the second tier and despite having several different striking partners of varying quality, his goalscoring record was good at a time when the side itself was struggling to return to the top with the Cup Final squad being dismantled and under investment in replacements.

The man who bought him didn’t last long either; Melia making way for Chris Cattlin in the autumn of 1983. It didn’t stop Connor making his mark in the second tier and despite having several different striking partners of varying quality, his goalscoring record was good at a time when the side itself was struggling to return to the top with the Cup Final squad being dismantled and under investment in replacements.

In his first full season, he missed only two first team games all season and was top scorer with 17 goals as Albion finished ninth in the league. His main strike partner Alan Young scored 12.

Connor got only one fewer in the 1984-85 season when the side finished sixth; the veteran Frank Worthington chipping in with eight goals in his only season with the Seagulls.

In 1985-86 Connor had two different strike partners in Justin Fashanu and the misfiring Mick Ferguson but still managed another 16 goals, including four braces.

The disastrous relegation season of 1986-87 contained a personal high for Connor when, in November 1986, he was selected as an over-age player (at 24) for England under 21s and scored in a 1-1 draw with Yugoslavia.

He had formed a useful partnership with Dean Saunders but, as money issues loomed, Saunders was sold to Oxford and soon, after being voted player of the season, Connor also left as the Albion were relegated; Barry Lloyd being unable to halt the slide back to the third tier.

Reflecting on his time at Brighton in a matchday programme interview, Connor said: “I really enjoyed my football, playing on the south coast. We also loved the lifestyle and my eldest daughter was born there, I loved playing in the atmosphere created at the Goldstone. There was a bond with the players and their partners, with Jimmy Melia and Mike Bamber, and it was like one big happy family.”

As Lloyd was forced to sell players, Connor returned to the top flight via a £200,000 move along the coast to newly-promoted Portsmouth. A terrible run of injuries plagued his Pompey career meaning he only managed 58 appearances and scored 14 goals over the course of three seasons.

A £150,000 transfer fee saw him join then Third Division Swansea City for the 1990-91 season and although he managed 39 appearances, he scored only six times.

Next stop was Bristol City in September 1991 for £190,000 but he scored only once in 16 games for the Robins. By the summer of 1993 he dropped out of the league to play for Conference side Yeovil Town and when he retired from playing he became a coach at Swindon Town.

John Ward took Connor as a coach to three clubs he managed, Bristol Rovers and City and then Wolverhampton Wanderers, where, across the reigns of several managers, he remained for the next 13 years. He worked at youth, reserve and first team level before becoming McCarthy’s assistant in 2008. He briefly took the reigns himself after McCarthy was sacked in early 2012 but, unable to halt the team’s relegation from the Premiership, reverted to assistant under the newly-appointed Ståle Solbakken for just four games of the new season before leaving Molineux.

Within three months, he resumed his role as McCarthy’s assistant when the pair were appointed at Portman Road. When McCarthy took over as the Republic of Ireland boss in November 2018, Connor once again was his assistant and in 2020 the pair found themselves at the top Cypriot side APOEL. In early 2021, McCarthy and Connor were back in tandem at Championship side Cardiff City.

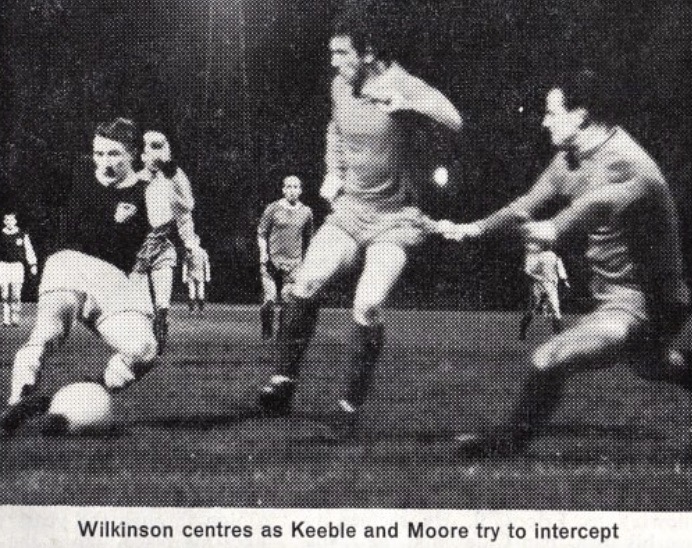

YORKSHIREMAN Howard Wilkinson was a key part of the first Albion side I watched. The former Sheffield Wednesday player was a speedy winger in

YORKSHIREMAN Howard Wilkinson was a key part of the first Albion side I watched. The former Sheffield Wednesday player was a speedy winger in

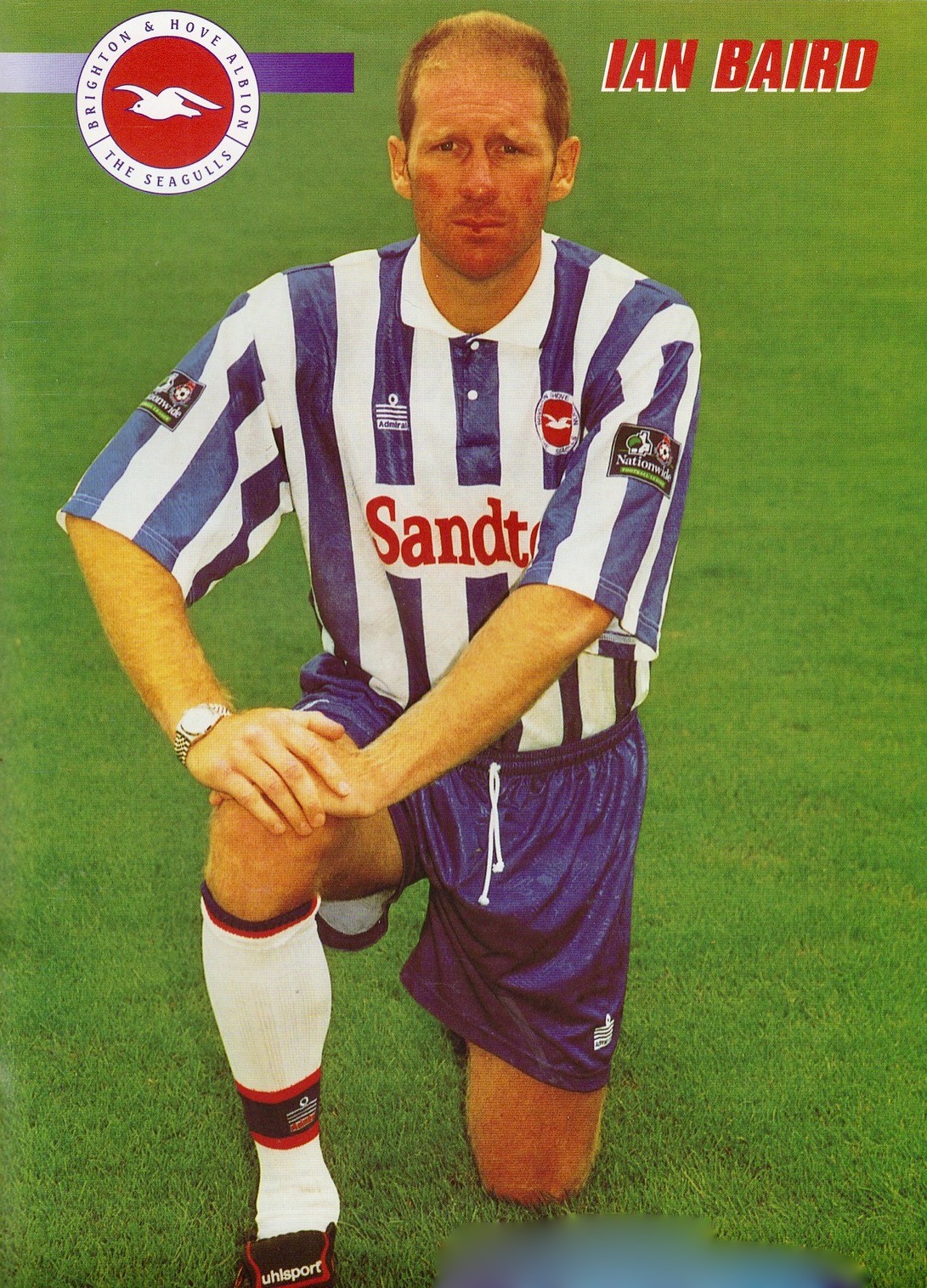

To be fair, Baird had a reasonable goalscoring record at Brighton, netting 14 in 41 games following a £35,000 move from Plymouth Argyle.

To be fair, Baird had a reasonable goalscoring record at Brighton, netting 14 in 41 games following a £35,000 move from Plymouth Argyle.

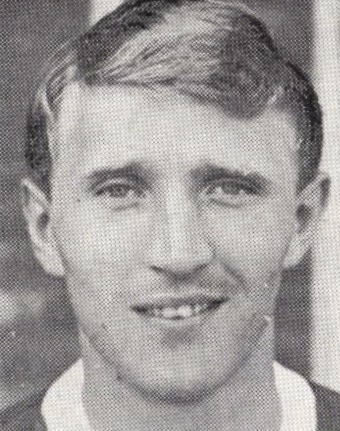

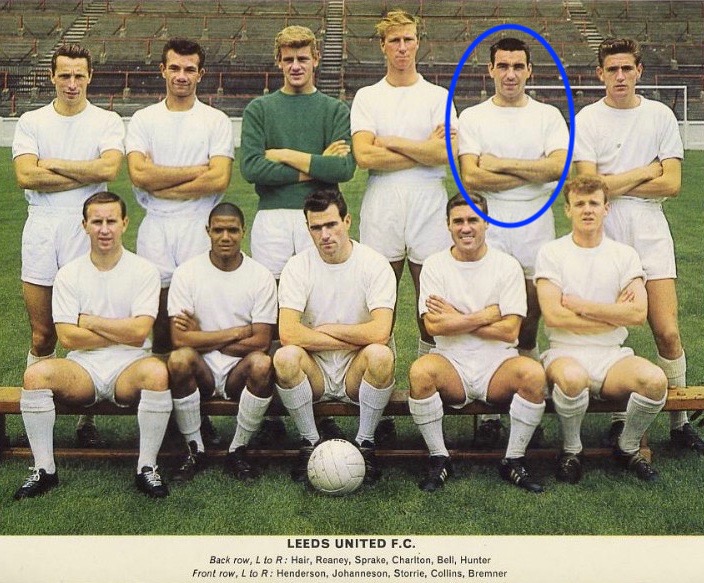

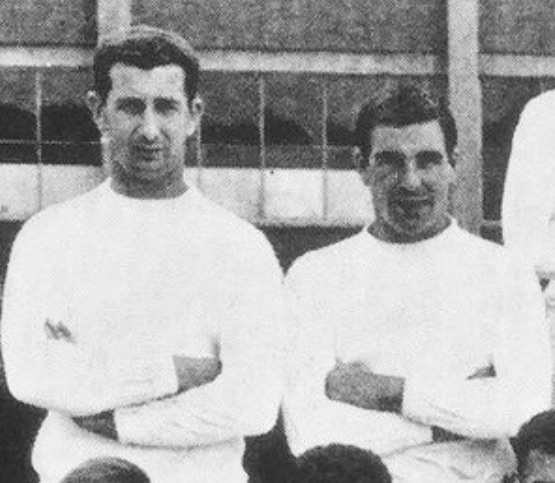

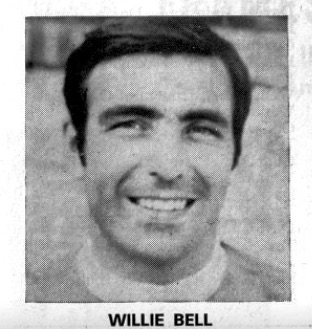

Goodwin (pictured below alongside Bell in a Leeds line-up) obviously knew the pedigree of the player and

Goodwin (pictured below alongside Bell in a Leeds line-up) obviously knew the pedigree of the player and

The matchday programme noted: “Willie is continuing his career as a player, but devotes a good deal of his time to the reserve side. He’s thoroughly enjoying this new phase to a fine career in the game.”

The matchday programme noted: “Willie is continuing his career as a player, but devotes a good deal of his time to the reserve side. He’s thoroughly enjoying this new phase to a fine career in the game.”