THERE WAS no shortage of tributes paid to Gerry Ryan when the former Albion winger died at the age of 68 on 15 October 2023.

Fellow Irish international Liam Brady, who appointed Ryan as his assistant when he took charge of the Seagulls in 1996, said: “Gerry was a wonderful team-mate. He was a very quick winger, very brave, and he took people on.

“We had some great games together and then we ended up on opposite sides, for Brighton and Arsenal, in the old First Division.”

Although Ryan and Brady’s time in charge happened during a turbulent time off the pitch, Brady pointed out: “We did a pretty good job in what were, of course, difficult circumstances, and I could see then just what Brighton meant to him – he was in love with the club so much.

“Off the pitch, Gerry was just a really nice guy. He was affable, unassuming and got on with everyone he came in contact with.”

That sentiment was echoed by teammate Gordon Smith who told the Albion website: “Gerry was always fired up to play.

“He was not always first choice, but he was still a very good player. He had this ability to be able to turn games around because he was quick and he could score goals.

“He was so reliable – he could fit into any position with his levels of fitness, ability and positional play.

“We were a very close group; we socialised a lot, we played golf, went to the races and Gerry was a key part of that – he was a really good laugh.”

Turlough O’Connor, another former team-mate, from his early days playing for Bohemians in Dublin, told the Irish Independent: “He was the most easygoing guy you’d ever meet, very laidback and always in a happy mood, and a very good footballer as well.

“He was comfortable both left and right, very good on the ball, and very quick, which helped. A very good crosser, he went by people, and was always a threat. He helped so many times laying on goals for me.”

Ryan was one of the most likeable Albion players for a huge number of fans, and I was one of them.

A versatile trier who was good enough to represent the Republic of Ireland on 18 occasions, the wholehearted Ryan might not make it into the all-time best Brighton XI but, if it was judged on affability, his name would be first on the team sheet.

A cruel twist of fate saw his career ended in a tackle made by his Irish teammate (and former Albion boss) Chris Hughton’s brother, Henry. Typically, Ryan bore no grudges, as stressed by former Argus Albion reporter John Vinicombe in an article published in May 1986 when the genial Irishman finally accepted that his career was over.

Describing “the immense dignity and true manliness that Ryan displayed in refusing to condemn or indeed utter any harsh word against the player responsible,” he added: “Where others have sued and raged, slandered, cursed and threatened, Ryan said nothing.”

It was 2 April 1985 when his career was ended by that Hughton tackle in a 1-1 draw with Crystal Palace at Selhurst Park.

“Never in his life has he shirked a tackle and the one that ended his career so unfortunately at Crystal Palace was typical of many he faced in his career,” said Alan Mullery, the manager who signed him for the Seagulls.

“As a person, he is a lovely and typical Irish personality,” Mullery said in the programme for the player’s testimonial game against Spurs at the Goldstone on 8 August 1986. “I can honestly say that I have never met a player who dislikes him or has a bad word to say about him. I will remember Gerry Ryan as being a special player and one of football’s nice people.”

Mullery also referred to a Sunday lunch he and his family had with Ryan and his wife at the time he signed. “When Gerry ordered roast beef and chips I must have known then that I had a very special sort of player. At the time, I was a little dubious but afterwards I had no regrets.”

Mullery had been over in Dublin watching Albion’s Mark Lawrenson playing for the Republic of Ireland and Derby’s Ryan was playing in the same side. He had been having talks about moving to Stoke City but Mullers persuaded him to join Brighton instead, and, in a strange quirk of fate, he made his debut in a 2-2 draw away to Stoke.

After they’d become teammates, Lawrenson was among those players appreciative of Ryan’s “mercurial” qualities. He said in a matchday programme: “He wasn’t the most confident of players but he had loads of ability. For a wide player, he would come in and get goals for you.”

A week after joining the Seagulls, Ryan became an instant hit with Albion fans when he scored on his home debut in a 5-1 win over Preston. He notched a total of nine goals in 34 appearances in that first season and went on to score 39 in a total of 199 games.

A week after joining the Seagulls, Ryan became an instant hit with Albion fans when he scored on his home debut in a 5-1 win over Preston. He notched a total of nine goals in 34 appearances in that first season and went on to score 39 in a total of 199 games.

Born in Dublin on 4 October 1955, Ryan was one of eight children. His early education was at the local convent in Walkinstown, a suburb to the south of Dublin where the family lived. At the age of eight he moved on to Drimnagh Castle School (it covered primary and secondary age groups).

At that stage, he was playing Gaelic football and hurling, at which he was capped at under-15 level by Dublin Schools. He didn’t play competitive football until he was 16 when he was introduced to a Dublin football club called Rangers AFC. He played alongside Kevin Moran, who later played for Manchester United, and Pat Byrne, who later played for Leicester City. Byrne and Ryan also played together for Bohemians, the oldest football club in Dublin.

Ryan joined the Dublin Corporation as a clerical officer on leaving school and played for Bohs as an amateur initially before becoming a part-timer on professional terms. By 18, Ryan was a first-team regular and, after collecting a League of Ireland Championship medal, was watched by Manchester United boss Tommy Docherty.

Docherty didn’t pounce then but, after Ryan had stayed four years with Bohemians, the ebullient Scot eventually returned to take him to England as his first signing for Derby County for a fee of £55,000.

The newly-appointed Docherty was determined to shake-up the club and while long-serving goalkeeper Colin Boulton was discarded along with striker Kevin Hector, Ryan, Scottish internationals Bruce Rioch and Don Masson, and Terry Curran and Steve Buckley were all introduced.

Ryan spoke about the way Docherty’s attitude towards him changed in an interview with Brian Owen of The Argus in 2016.

“One minute you were the blue-eyed boy, the next he wouldn’t even talk to you,” he said. Ryan made a hamstring injury worse by playing when Docherty insisted he was fit enough, and ended up sidelined for three months. “He didn’t like me then! That’s the way he was, he would turn on you, and he turned on me.”

Within a year, Docherty accepted Brighton’s £80,000 offer for Ryan and, as he was weighing up whether to choose the Seagulls or Stoke City, Ryan consulted the legendary Republic of Ireland and ex-Leeds midfielder Johnny Giles to ask his opinion.

“Gilesy said ‘Stoke have been in and out of the First Division forever but there is something going on down at Brighton. They get great crowds and it’s a beautiful place.’ I went to Brighton that weekend and absolutely loved it,” Ryan told Owen.

It was on 25 September 1978 winger Ryan arrived, prompting the departure of popular local lad Tony Towner after eight years at the Albion.

Five months before Ryan arrived at the Goldstone, he made his international debut, featuring for the first time in April 1978 in a 4-2 win over Turkey at Lansdowne Road. He only scored once for the Republic, but it was a cracking overhead kick in a 3-1 defeat against West Germany.

He was one of four regular Eire internationals playing for Albion at the time: Lawrenson, Tony Grealish and Michael Robinson the others.

His final appearance for his country came in a 0-0 draw against Mexico at Dalymount Park in 1984.

Ryan was part of some all-time history-making moments during his time with the Albion – scoring at St James’s Park in the 3-1 win over Newcastle on 5 May 1979 to clinch promotion to the top division for the first time, and burying the only goal of the game as unfancied Albion beat Brian Clough’s European champions Nottingham Forest, who’d previously not lost at home for two and a half years.

My personal favourite came on 29 December 1979 at the Goldstone when he ran virtually the entire length of a boggy, bobbly pitch to score past Joe Corrigan in the goal at the South Stand end to top off a 4-1 win over Manchester City. Ryan himself reckoned it was “the best goal I ever scored” as he recounted in a May 2020 BBC Sussex Sport interview with Johnny Cantor.

My personal favourite came on 29 December 1979 at the Goldstone when he ran virtually the entire length of a boggy, bobbly pitch to score past Joe Corrigan in the goal at the South Stand end to top off a 4-1 win over Manchester City. Ryan himself reckoned it was “the best goal I ever scored” as he recounted in a May 2020 BBC Sussex Sport interview with Johnny Cantor.

It was one of the most superb individual goals I saw scored and, when he was trying to recuperate from the horrific leg break which ultimately ended his career, I wrote to him in hospital to say what a special memory it held for me.

I was delighted to receive a grateful reply from him, and he has held a special place in my Albion memory bank ever since.

There were other stand-out occasions, two of which came against Liverpool:

in February 1983 at Anfield when he opened the scoring in Albion’s memorable 2-1 FA Cup triumph en route to the final, and, in the following season, at the Goldstone when he and Terry Connor were on target in Second Division Albion’s 2-0 win over the Reds in the same competition, the first-ever live FA Cup match (other than finals) to be shown (previously any television coverage of FA Cup ties was only ever recorded highlights).

If the modern-day reader can’t quite put the feat in perspective, it is worth pointing out that Liverpool, managed by Joe Fagan, went on to win the League Cup, the League title and the European Cup that season.

Danny Wilson hadn’t long since joined the Albion and, in an interview with the Seagull matchday programme in 2003, he recalled: “That has to be my favourite memory from all my time at the Goldstone. Back then, Liverpool were just awesome, and to beat them like we did was virtually unheard of.”

Ryan’s involvement in the 1983 Cup run was hampered by a hamstring injury which meant he missed out on the semi-final. But, in the days of only one substitute, he was on the bench for the final and, when the injured Chris Ramsey couldn’t continue, Ryan went on at Wembley and did a typically thorough job at right-back.

Following Albion’s relegation, as the big-name players departed the Goldstone, Ryan’s versatility and play-anywhere attitude came to the fore and, in his last two seasons with the club he was often selected as a centre-forward, although he was not a prolific goalscorer from that position.

After he was forced to quit playing, Ryan took what was then quite a familiar route for ex-players and became a pub licensee, running the Witch Inn at Lindfield, near Haywards Heath. Ryan and goalkeeper Graham Moseley, who he’d known from his days at Derby, were neighbours in Haywards Heath.

However, when another of his former Republic of Ireland teammates, Liam Brady, was appointed Albion manager in 1994, it was an inspired choice for him to appoint Ryan as his assistant.

When that all-too-brief managerial spell came to a messy close, Ryan returned to his pub, and then moved back to the family home in Walkinstown. Ryan’s son Darragh played 11 games for the Albion in the late 1990s.

Sadly, in August 2007, Ryan suffered a stroke, and three years later he was diagnosed with kidney cancer. On his death, his family paid tribute to the care he was given by the staff of Our Lady’s Hospice, Harold’s Cross and to the staff of Lisheen Nursing Home, Dr Brenda Griffin, the Beacon Renal Unit, Tallaght, and Tallaght Hospital Renal Unit “for the excellent care given to Gerry over the past number of years”.

Pictures from a variety of sources but mainly from my scrapbook, the matchday programme and The Argus.

Ever-present Wilson in action against Millwall at The Den

Ever-present Wilson in action against Millwall at The Den

A bare-chested Wilson was pictured (above) in the Albion dressing room alongside Mullery enjoying the celebratory champagne after promotion was clinched courtesy of a 3-2 win over Sheffield Wednesday on 3 May 1977. But that game was his Goldstone swansong.

A bare-chested Wilson was pictured (above) in the Albion dressing room alongside Mullery enjoying the celebratory champagne after promotion was clinched courtesy of a 3-2 win over Sheffield Wednesday on 3 May 1977. But that game was his Goldstone swansong. Wilson in an Albion line-up alongside Peter Ward

Wilson in an Albion line-up alongside Peter Ward

When Lawrenson was fit to return, Mullery sprung a surprise by utilising him in midfield, but it was an inspired decision and he stayed there for the rest of the season, helping Albion to finish a respectable 16th of 22.

When Lawrenson was fit to return, Mullery sprung a surprise by utilising him in midfield, but it was an inspired decision and he stayed there for the rest of the season, helping Albion to finish a respectable 16th of 22.

Perhaps it was surprising, though, that champions Liverpool were the ones to snap him up, particularly as Ian Rush and Kenny Dalglish were in tandem as first choice strikers.

Perhaps it was surprising, though, that champions Liverpool were the ones to snap him up, particularly as Ian Rush and Kenny Dalglish were in tandem as first choice strikers. Nevertheless, asked many years later to describe his proudest moment in football, he maintained: “Scoring the winning goal in the FA Cup semi-final that meant that a bunch of mates at Brighton were going to Wembley in 1983.”

Nevertheless, asked many years later to describe his proudest moment in football, he maintained: “Scoring the winning goal in the FA Cup semi-final that meant that a bunch of mates at Brighton were going to Wembley in 1983.”

He had yet more Wembley heartache during a two-year spell with Queen’s Park Rangers, being part of their losing line-up in the 3-0 league cup defeat to Oxford United in 1986.

He had yet more Wembley heartache during a two-year spell with Queen’s Park Rangers, being part of their losing line-up in the 3-0 league cup defeat to Oxford United in 1986.

STEVE Gatting played at Wembley three times for Brighton having twice been denied the opportunity by Arsenal.

STEVE Gatting played at Wembley three times for Brighton having twice been denied the opportunity by Arsenal.

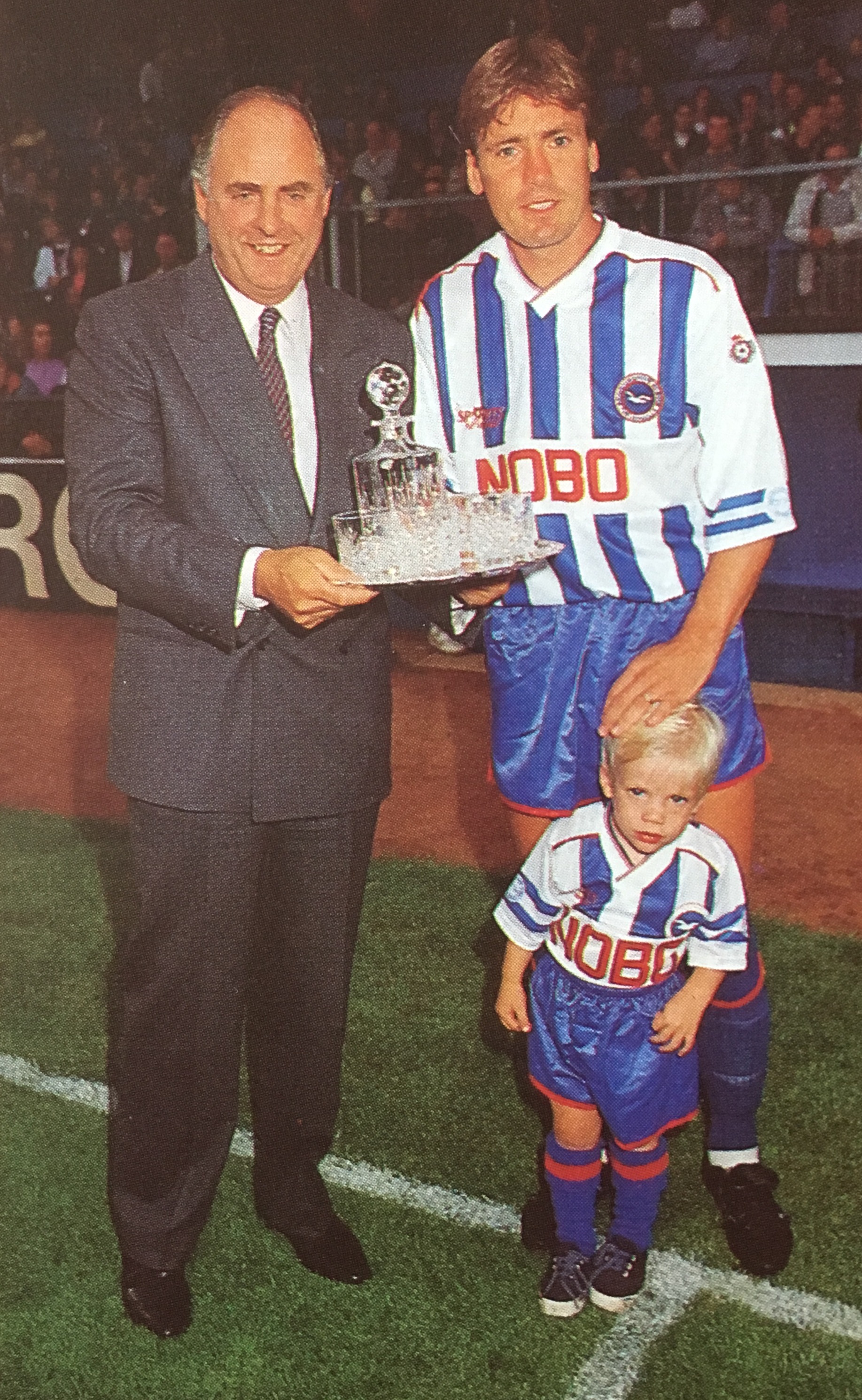

A cut glass decanter and glasses from chairman Dudley Sizen at Gatting’s testimonial

A cut glass decanter and glasses from chairman Dudley Sizen at Gatting’s testimonial

JIMMY Case remains one of my all-time favourite Albion players.

JIMMY Case remains one of my all-time favourite Albion players. The triumphs and trophies kept coming with Case enjoying the ride but by 1980-81 he was beginning to be edged out by Sammy Lee, and manager Bob Paisley didn’t look kindly on some of the off-field escapades Case was involved in with fellow midfielder Ray Kennedy.

The triumphs and trophies kept coming with Case enjoying the ride but by 1980-81 he was beginning to be edged out by Sammy Lee, and manager Bob Paisley didn’t look kindly on some of the off-field escapades Case was involved in with fellow midfielder Ray Kennedy.

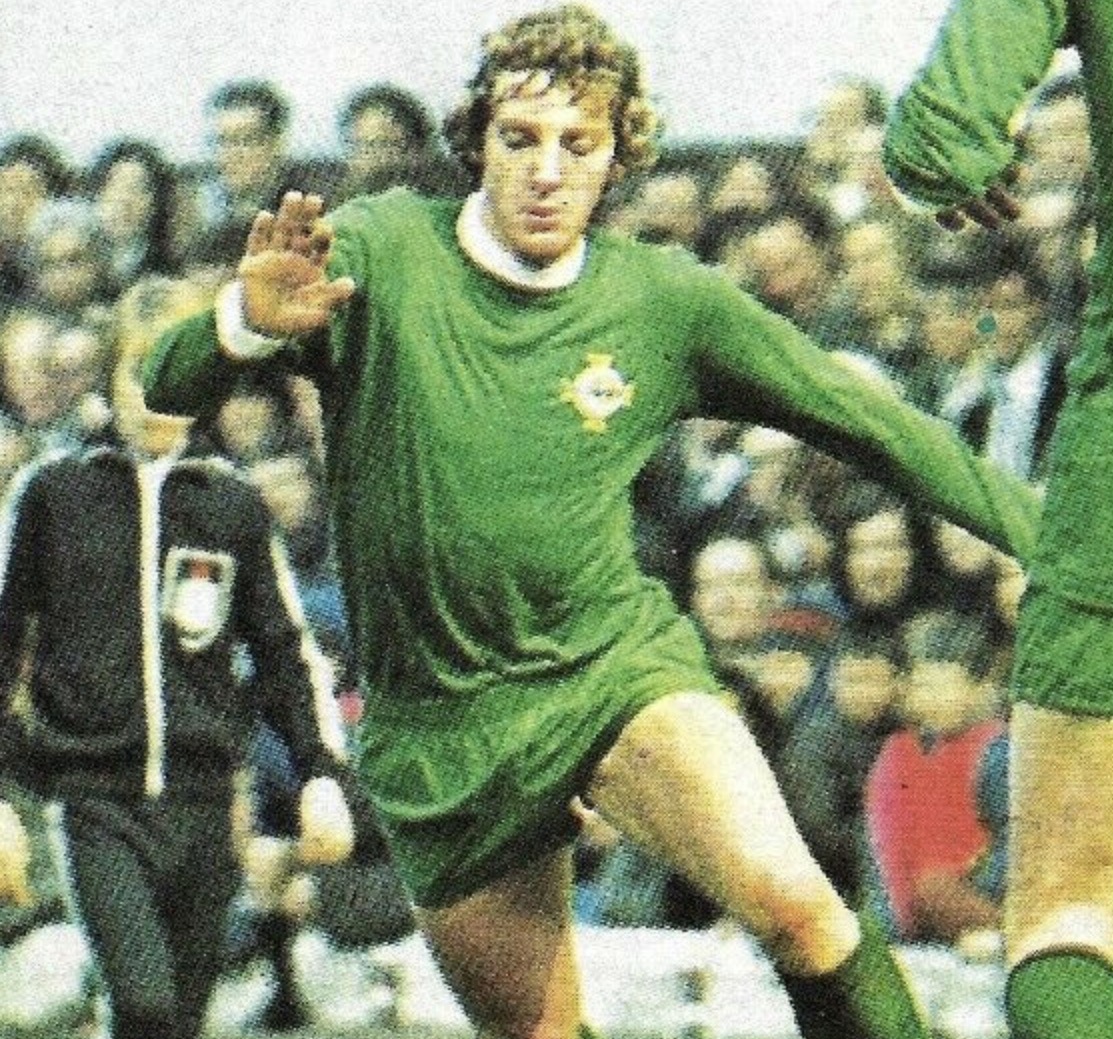

EXPERIENCED Northern Irish international full-back Sammy Nelson was an Arsenal legend who joined Brighton towards the end of his career.

EXPERIENCED Northern Irish international full-back Sammy Nelson was an Arsenal legend who joined Brighton towards the end of his career. Leading up to that competition, Nelson had played a significant part in helping Albion to what remained their highest ever finish in the football pyramid – thirteenth place – until the 2022-23 season.

Leading up to that competition, Nelson had played a significant part in helping Albion to what remained their highest ever finish in the football pyramid – thirteenth place – until the 2022-23 season.