WHEN Michael Robinson died of cancer aged 61 on 28 April 2020, warm tributes were paid in many quarters to the former Brighton, Liverpool and Republic of Ireland international who became a big TV celebrity in Spain.

“We have lost a very special guy, a lovely person and someone I’m proud to have known both on and off the pitch,” his former teammate Gordon Smith told Spencer Vignes. “He was one of the boys, one of the good guys.”

It seemed like half a world away since Robinson had charged towards Gary Bailey’s goal in the dying moments of the 1983 FA Cup Final only inexplicably to pass up the opportunity of scoring a Wembley winner to lay the ball off to Smith.

“With Michael bursting forward and having turned the United defence inside out, I was genuinely expecting him to shoot and had put myself in a position to pick up any possible rebound,” Smith recounted. “Instead he squared it to me and we all know what happened next.”

Robinson’s next two competitive matches also took place at Wembley:

- He once again led the line for Brighton when the Seagulls were crushed 4-0 by Manchester United in the cup final replay on 26 May. It turned out to be his last game for the Albion.

- Three months later he was in the Liverpool side who lost 2-0 to United in the FA Charity Shield season-opening fixture between league champions and FA Cup winners, following his £200,000 move from relegated Brighton.

It was hardly surprising Robinson didn’t hang around at the Goldstone: the Seagulls had given him a platform to resurrect a career that had stalled at Manchester City, but the striker had several disputes with the club and the newspapers were always full of stories linking him with moves to other clubs.

Perhaps it was surprising, though, that champions Liverpool were the ones to snap him up, particularly as Ian Rush and Kenny Dalglish were in tandem as first choice strikers.

Perhaps it was surprising, though, that champions Liverpool were the ones to snap him up, particularly as Ian Rush and Kenny Dalglish were in tandem as first choice strikers.

But at the start of the 1983-84 season, Joe Fagan’s Liverpool had several trophies in their sights and Robinson scored 12 times in 42 appearances as the Merseyside club claimed a treble of the First Division title, the League Cup, and the European Cup.

It took him a while to settle at the Reds because by his own admission he was in awe of the players around him but advice from Fagan to play without the metal supports he’d worn in his boots for six years previously (to protect swollen arches) paid off.

“It made a hell of a difference,” he said. “I felt a lot sharper and so much lighter on my feet.” In the first game without them, Robinson scored twice in a European game at Anfield, then he got one in a Milk Cup tie versus Brentford and scored a hat-trick in a 3-0 league win at West Ham.

Nevertheless, asked many years later to describe his proudest moment in football, he maintained: “Scoring the winning goal in the FA Cup semi-final that meant that a bunch of mates at Brighton were going to Wembley in 1983.”

Nevertheless, asked many years later to describe his proudest moment in football, he maintained: “Scoring the winning goal in the FA Cup semi-final that meant that a bunch of mates at Brighton were going to Wembley in 1983.”

One of two sons born to Leicester publican Arthur Robinson on 12 July 1958, Michael followed in his father’s footsteps in playing for Brighton. Arthur played for the club during the Second World War when in the army, and also played for Leyton Orient.

When he was four, Robinson moved to Blackpool where his parents took over the running of a hotel in the popular seaside resort. The young Robinson first played football on Blackpool beach with his brother.

After leaving Thames Primary School, it was at Palatine High School that he first got involved in organised football, and, before long, he caught the eye of the local selectors and represented Blackpool Schools at under 15 level, even though he was only 13.

Amongst his teammates at that level was George Berry, who ironically was Robinson’s opponent at centre half in his first Albion match, against Wolverhampton Wanderers.

The young Robinson also played for Sunday side Waterloo Wanderers in Blackpool and when still only 13 he was invited for trials at Chelsea, by assistant manager Ron Suart, who had played for and managed Blackpool.

Although he was asked to sign schoolboy forms, Robinson’s dad thought it was too far from home. Coventry, Blackpool, Preston and Blackburn were also keen and the North West clubs had the edge because he wouldn’t have to leave home.

Eventually he chose Preston and on his 16th birthday signed as an apprentice. At the time, Mark Lawrenson was also there, training with the youngsters, and Gary Williams was already on the books.

After two years as an apprentice, he signed professional and began to push for a first team place with the Lillywhites. With former World Cup winner Nobby Stiles in charge, in 1978-79, Robinson scored 13 goals in 36 matches, was chosen Preston fans’ Player of the Year and his form attracted several bigger clubs.

In a deal which shocked the football world at the time, the flamboyant Malcolm Allison paid an astonishing £756,000 to take him to Manchester City. It was a remarkable sum for a relatively unproven striker.

The move didn’t work out and after scoring only eight times in 30 appearances for City, Robinson later admitted: “I’d never kicked a ball in the First Division and the fee was terrifying. If I had cost around £200,000 – a price that at that time was realistic for me – I would have been hailed as a young striker with bags of promise.”

It was Brighton manager Alan Mullery, desperate to bolster his squad as Albion approached their second season amongst the elite, who capitalised on the situation.

“I received the go ahead to make some major signings in the summer of 1980,” Mullery said in his autobiography. Mullery, had the support of vice-chairman Harry Bloom – current chairman Tony Bloom’s grandfather – even though chairman Mike Bamber was keener to invest in the ground.

“I could see he’d lost confidence at City and I made a point of praising him every chance I got,” said Mullery. “I asked him to lead the line like an old-fashioned centre forward and he did the job very well.”

Robinson told the matchday programme: “When Brighton came in for me, I needed to think about the move…12 months earlier I had made the biggest decision of my life and I didn’t want to be wrong again.”

In Matthew Horner’s authorised biography of Peter Ward, He shot, he scored, Mullery told him: “When I signed Michael Robinson it was because I thought Ward was struggling in the First Division and that Robinson could help take the pressure off him. Robinson was big, strong, and powerful and he ended up scoring 22 goals for us in his first season.”

The first of those goals came in his fourth game, a 3-1 league cup win over Tranmere Rovers, and after that, as a permanent fixture in the no.9 shirt, the goals flowed.

With five goals already to his name, Robinson earned a call up to the Republic of Ireland squad. Although born in Leicester, his mother was third generation Irish and took out Irish citizenship so that her son could qualify for an Irish passport. It was also established that his grandparents hailed from Cork.

He made his international debut on 28 October 1980 against France. It was a 1982 World Cup qualifier and the Irish lost 2-0 in front of 44,800 in the famous Parc des Princes stadium.

Nevertheless, the following month he scored for his country in a 6-0 thrashing of Cyprus at Lansdowne Road, Dublin, when the other scorers were Gerry Daly (2), Albion teammate Tony Grealish, Frank Stapleton – and Chris Hughton!

In April 1982, Robinson, Grealish and Gerry Ryan were all involved in Eire’s 2-0 defeat to Algeria, played in front of 100,000 partisan fans, and for a few moments on the return flight weren’t sure they were going to make it home. The Air Algeria jet developed undercarriage problems and had to abort take-off. Robinson told the Argus: “I thought we were all going to end up as pieces of toast. But the pilot did his stuff and we later changed to another aircraft.”

Although not a prolific goalscorer for Ireland, he went on to collect 24 caps, mostly won when Eoin Hand was manager. He only appeared twice after Jack Charlton took charge.

But back to the closing months of the 1980-81 season…while only a late surge of decent results kept Albion in the division, Robinson’s eye for goal and his never-say-die, wholehearted approach earned him the Player of the Season award.

As goal no.20 went in to secure a 1-1 draw at home to Stoke City on 21 March, Sydney Spicer in the Sunday Express began his report: “Big Mike Robinson must be worth his weight in gold to Brighton.”

However, the close season brought the shock departure of Mullery after his falling out with the board over the sale of Mark Lawrenson and the arrival of the defensively-minded Mike Bailey.

Bailey had barely got his feet under the table before Robinson was submitting a written transfer request, only to withdraw it almost immediately.

He said he wanted a move because he was homesick, but after talks with chairman Bamber, he was offered an incredible 10-year contract to stay, and said the club had “fallen over themselves to help me”.

Bamber told the Argus: “I have had a very satisfactory talk with Robinson and now everybody’s contracts have been sorted out. It has not been easy to persuade him to stay.”

Even though Bailey led the Seagulls to their highest-ever finish of 13th, it was at the expense of entertainment and perhaps it was no surprise that Robinson’s goal return for the season was just 11 from 39 games (plus one as sub).

The 1982-83 season had barely got underway when unrest in the club came to the surface. Steve Foster thought he deserved more money having been to the World Cup with England and Robinson questioned the club’s ambition after chairman Bamber refused to sanction the acquisition of Charlie George, the former Arsenal, Derby and Southampton maverick, who had been on trial pre-season.

Indeed, Robinson went so far as to accuse the club of “settling for mediocrity” and couldn’t believe manager Bailey was working without a contract. Bamber voiced his disgust at Robinson, claiming it was really all about money.

The club tried to do a deal whereby Robinson would be sold to Sunderland, with Stan Cummins coming in the opposite direction, but it fell through.

Foster and Robinson were temporarily left out of the side until they settled their differences, returning after a three-game exile. But within four months it was the manager who paid the price when he was replaced in December 1982 by Jimmy Melia and George Aitken.

Exactly how much influence the managerial pair had on the team is a matter of conjecture because it became a fairly open secret that the real power was being wielded by Foster and Robinson.

On the pitch, the return of the prodigal son in the shape of Peter Ward on loan from Nottingham Forest had boosted crowd morale but didn’t really make a difference to the inexorable slide towards the bottom of the league table.

Ward scored a famous winner as Manchester United were beaten 1-0 at the Goldstone a month before Bailey’s departure, but he only managed two more in a total of 20 games and Brian Clough wouldn’t let him stay on loan until the end of the season.

Albion variously tried Gerry Ryan, Andy Ritchie and, after his replacement from Leeds, Terry Connor, to partner Robinson in attack. But Connor was cup-tied and Ryan bedevilled by injuries, so invariably Smith was moved up from midfield.

Robinson would finish the season with just 10 goals to his name from 45 games (plus one as sub) – not a great ratio considering his past prowess.

The fearless striker also found himself lucky to be available for the famous FA Cup fifth round tie at Liverpool after an FA Commission found him guilty of headbutting Watford goalkeeper Steve Sherwood in a New Year’s Day game at the Goldstone.

The referee hadn’t seen it at the time but video evidence of the incident was used and the blazer brigade punished him with a one-match ban and a £250 fine. Robinson claimed it had been an accident…but it was one that left Sherwood needing five stitches. The ban only came into effect the day after the Liverpool tie, and he missed a home league game against Stoke City instead.

In the run-up to the FA Cup semi-final with Sheffield Wednesday, Robinson was reported to be suffering with a migraine although he told Brian Scovell it was more to do with tension, worrying about the possibility of losing the upcoming tie.

Nevertheless, he told the Daily Mail reporter: “When I was with Preston, I suffered a depressed fracture of the skull and have had headaches ever since. This week it’s been worse with the extra worry about the semi-final.”

Manager Melia, meanwhile was relieved to know Robinson would be OK and almost as a precursor to what happened told John Vinicombe of the Evening Argus: “Robbo is a very important member of our team and he’s the man who can win it for us.

“It is Robbo who helps finish off our style of attacking football and I know he’ll do the business for us on the day.”

Reports of the semi-final were splashed across all of the Sunday papers, but I’ll quote the Sunday Express. Under the headline MELIA’S MARVELS, reporter Alan Hoby described the key moment of the game.

“In a stunning 77th minute breakaway, Case slipped a beauty forward to the long-striding Gordon Smith whose shot was blocked by Bob Bolder.

“Out flashed the ball to Smith again and this time the cultured Scot crossed for Mike Robinson to rap it in off a Wednesday defender.”

Other accounts noted that defender Mel Sterland had made a vain attempt to stop the ball with his hand, but the shot had too much power.

When mayhem exploded at the final whistle, a beaming Robinson appeared on the pitch wearing a crumpled brown hat thrown from the crowd to acknowledge the ecstatic Albion supporters.

In one of many previews of the Final, Robinson was interviewed by Shoot! magazine and sought to psyche out United by saying all the pressure was on them.

“That leaves us to stride out from that tunnel with a smile and a determination to make everyone proud of us,” he said.

“Nobody seems to give us a prayer. They all seem glad that ‘little’ Brighton has reached the Final, but only, I suspect, because they expect to see us taken apart by United.”

Everyone knows what happened next and quite why the normally-confident Robinson didn’t take on his golden opportunity to win the game for Brighton in extra time remains a mystery.

However, as mentioned earlier, within months ‘little’ Brighton was a former club and Robinson had taken to a much bigger stage. This is Anfield reflected on his short time at Anfield as “a golden opportunity for him” and recalls that it turned out to be “the best and most successful season of his career”.

He had yet more Wembley heartache during a two-year spell with Queen’s Park Rangers, being part of their losing line-up in the 3-0 league cup defeat to Oxford United in 1986.

He had yet more Wembley heartache during a two-year spell with Queen’s Park Rangers, being part of their losing line-up in the 3-0 league cup defeat to Oxford United in 1986.

The move which would lay the foundations for what has become a glorious career on TV arose in January 1987 when Robinson moved to Spain to play for Osasuna, scoring 12 times in 59 appearances before retiring through injury aged 31.

Robinson completely embraced the Spanish way of life, learned the language sufficiently to be an analyst for a Spanish TV station’s coverage of the 1990 World Cup, and took Spanish citizenship.

His on-screen work grew and the stardom Robinson achieved on Spanish TV attracted some of the heavyweight English newspapers to head out to Spain to find out how he had managed it.

For instance, Elizabeth Nash interviewed him for The Independent in 1997 and discovered how he had sold his house in Windsor and settled in Madrid.

Meanwhile, in a truly remarkable interview Spanish-based journalist Sid Lowe did with Robinson for The Guardian in 2004, we learned how that FA Cup semi-final goal was his proudest moment in football and that Steve Foster was his best friend in football.

In June 2017, his TV programme marked the 25th anniversary of Barcelona’s first European Cup win at Wembley, with some very studious analysis. On Informe Robinson (‘Robinson Report), he said: “Wembley was a turning point in the history of football. Cruyff gave the ball back to football.”

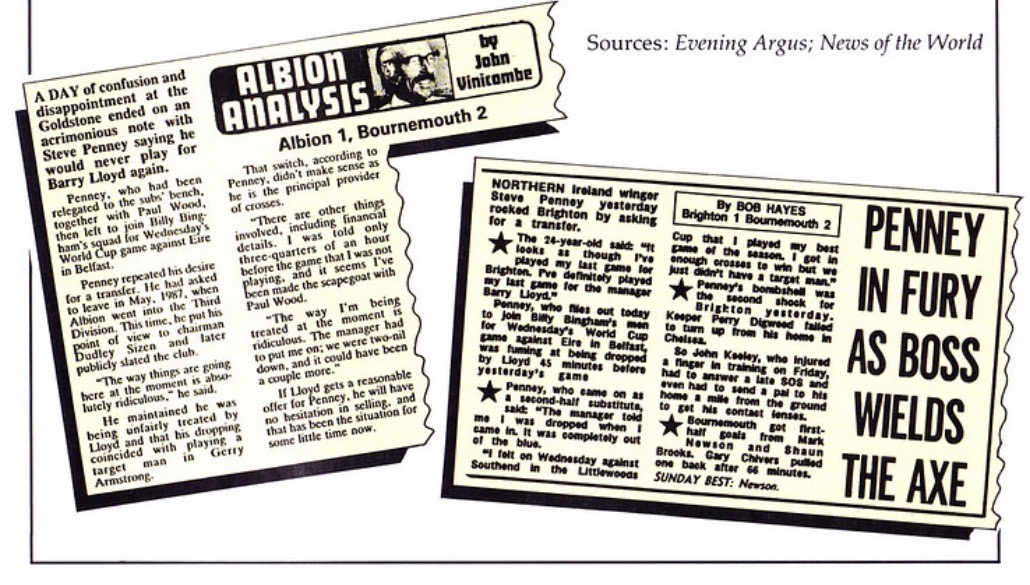

Manager Lloyd and Penney also fell out, principally over Penney putting country before club. “He’d play for them, then come back injured. That didn’t please me,” said Lloyd. “It was a crying shame. He just wanted to play but was so plagued with injuries it was beyond belief.”

Manager Lloyd and Penney also fell out, principally over Penney putting country before club. “He’d play for them, then come back injured. That didn’t please me,” said Lloyd. “It was a crying shame. He just wanted to play but was so plagued with injuries it was beyond belief.”