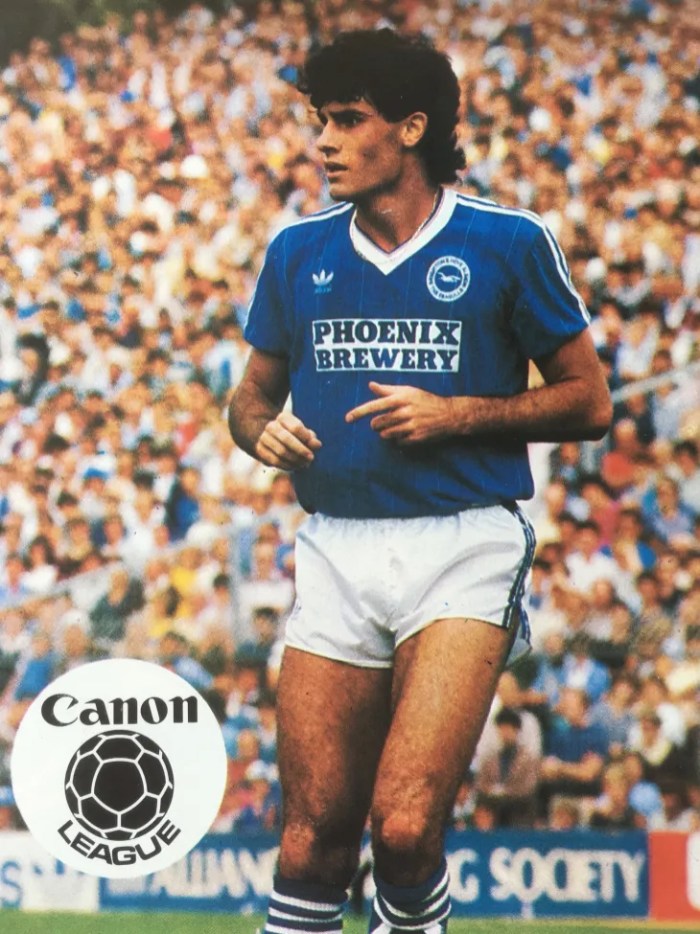

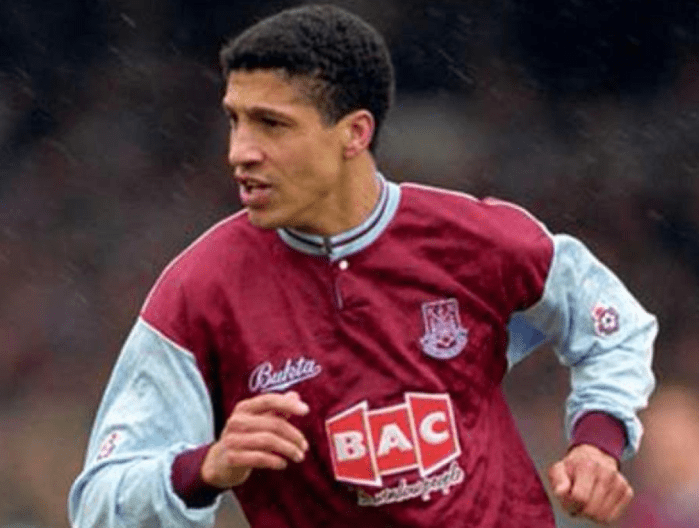

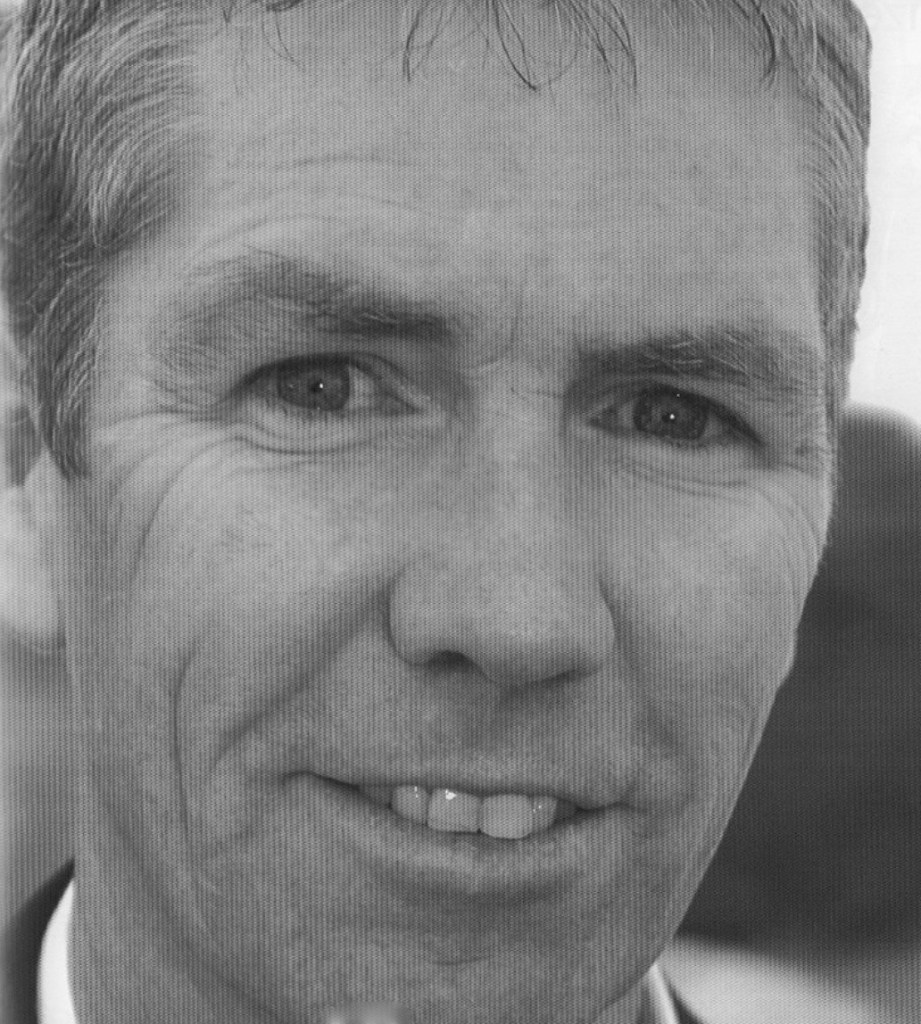

DEFENDER-turned-broadcaster Gary O’Reilly’s first ever league goal was scored for Brighton against Crystal Palace, a club he later scored for in a FA Cup final before rejoining the Seagulls.

That goal came in only his fourth Albion game, on 15 September 1984, after a £45,000 move from Spurs and was enough to ensure a 1-0 win in front of a 15,044 Goldstone Ground crowd against an Eagles side who had just installed Steve Coppell as manager.

Although O’Reilly had collected a UEFA Cup-winners’ medal that May as a non-playing squad member of the Tottenham side that beat Anderlecht 4-3 on penalties (after the two-legged final ended 2-2), opportunities were few and far between at White Hart Lane.

He still had two years of his contract remaining, but O’Reilly requested a transfer and Chris Cattlin snapped him up. Cattlin later admitted: “I watched him eight times before signing him, and six times with Tottenham Reserves he had stinkers. But I thought then he had great potential.”

In a 2001 interview with the Argus, O’Reilly said: “It was a gamble and I took a cut in pay. Spurs had an embarrassment of riches as far as talent was concerned. Spurs were only giving me about 15 games a season and at Brighton I played regularly in a strong side.

“Brighton included the likes of Chris Hutchings, Jimmy Case, Eric Young, Neil Smillie, Danny Wilson, Joe Corrigan, Steve Penney, Terry Connor, Steve Gatting and Frank Worthington and apologies to anyone I’ve forgotten.

“Jimmy had so much experience and Danny was such a driving force who led by example. Frank Worthington? I had this cliched image of him regarding his socialising but I had that vision shattered.

“He was 36 but was so professional, with a desire to win. He was open with his encouragement, free with his advice and a great rock ‘n’ roll fan! I used to make sure he gave me a lift home from training because we both liked loud rock music.”

If O’Reilly was confident the blend between old-stagers and talented youngsters would be enough to win promotion back to the elite, his hopes were shattered when Case was sold to Southampton in March 1985.

“We sold Jimmy Case in the March and I nearly took the door off the hinges in Cattlin’s office,” he recalled in a matchday programme article. “I asked him what the hell he was doing selling Jimmy! Were we serious about getting promoted? Were we serious about getting into the play-offs?

“Jimmy went to Southampton and they had success with him in their team in the First Division. It was no surprise. How many European Cup medals does Jimmy have that say ‘wiinner’? That’s what Jimmy brought to the team here and he was a massive loss when he went.”

Indeed, Albion ended up just a couple of points shy of the promotion places.

O’Reilly and Young (who also later played for Palace) became an almost permanent centre-back pairing in that 1984-85 season, although, in its fledgling stages, Cattlin admitted he played Graham Pearce in between them “to allow the central defensive pair to learn their trade and settle down into a partnership”.

O’Reilly recalled: “We had a good defence (which equalled the fewest-goals-conceded record of 34) and when we clicked up front we would win 4-0, 5-0. We played good football, through midfield, with pace, power and discipline. I learned so much. It was a brilliant time.”

The following season saw Albion finish in mid-table and Cattlin was relieved of his duties before the final game. There had been a consolation of sorts that they reached the quarter-finals of the FA Cup when a Jimmy Case-led Southampton (with Peter Shilton in goal) saw off the Seagulls 2-0 in front of a bumper 25,069 crowd (most attendances that season struggled to reach 10,000).

Before that March match, O’Reilly thought he’d scored two more against Palace but his efforts in the New Year’s Day encounter at the Goldstone were ruled out. Nonetheless Dean Saunders and a Danny Wilson penalty secured a 2-0 win for the Seagulls.readcrystalpalace.com says that game is “mainly remembered by Palace fans for a scandalous dive by Terry Connor which earned Brighton a penalty”.

Nonetheless, maybe O’Reilly had caught Coppell’s eye because, in January 1987, Cattlin’s successor Alan Mullery said Palace were in for him and Albion needed the money – £40,000 – to pay the whole club’s wage bill for the next month.

Mullery had ridden on the crest of a wave during his previous five years with the club but on his return found it much-changed. Attendances at the Goldstone were often below 10,000 and, from the word go, Mullery had been instructed to offload high-earners to stem the outflow of cash.

“The playing squad was cut back to the minimum and I had no room to manoeuvre,” he wrote in his autobiography.

Although he’d played 92 games for the Seagulls, O’Reilly had missed several matches in the first half of the season with a troublesome hamstring strain and by Christmas the side were struggling near the bottom of the table.

He said: “Mullery, who was always very honest, said there was no pressure to leave but that if I didn’t go there wouldn’t be enough money to pay the wages.”

Within days of his move to Selhurst Park, O’Reilly was followed out of the exit by a shell-shocked Mullery, who said: “Of course the cuts had left the team struggling but I could have pulled things round if the board had trusted and believed in me. Instead, I’d been stitched up.”

For his part, O’Reilly said: “I went, not so the wages could be paid, but as a career move and it proved the right one.

“Palace got promotion (in 1989) and made it to the FA Cup final (1990) and I scored in the semis against Liverpool and the final against Manchester United.”

None of the much-hyped enmity between Brighton and Palace affected O’Reilly’s switch to Croydon. “I didn’t have any issues with anybody and neither did they with me,” he said in a matchday programme interview. “I didn’t feel any animosity. I was welcomed and we got on really well. The fans realised I didn’t go to Palace to hate, I went to Palace to win.

“I’d played against them a number of times and Steve (Coppell) wanted to develop the squad and make me part of it.”

O’Reilly told Spencer Vignes: “There were the beginnings of a seriously decent side there. Ian Wright and Mark Bright were just coming through, Andy Gray was already there and John Salako, Gareth Southgate in the youth team – a lot of good talent.”

And of Coppell, he said: “Steve had the hunger and drive that made you want to win. That attitude was reflected in the players he acquired.”

Scoring that goal against United in the 1990 FA Cup Final helped O’Reilly fulfil a childhood dream although ultimately there was the disappointment of United equalising (making it 3-3) through Mark Hughes in extra time and going on to win the replay.

“The FA Cup goal was a set play which was no surprise because we worked hard at set plays,” he recalled. It was from Phil Barber’s free-kick on the right that O’Reilly put Palace ahead after 18 minutes, his header looping over goalkeeper Jim Leighton.

United recovered to lead 2-1 before sub Ian Wright, only six weeks after breaking his leg, went on to score twice, in the 72nd minute and again at the start of extra-time before Hughes’ equaliser seven minutes from the end.

O’Reilly played 79 times over three and a half seasons at Selhurst Park but the aforementioned Young and Andy Thorn were the regular centre-back pairing in 1990-91 when Palace finished third in the top division and also won the Full Members’ Cup. O’Reilly went out on loan to Birmingham City, although he only played once.

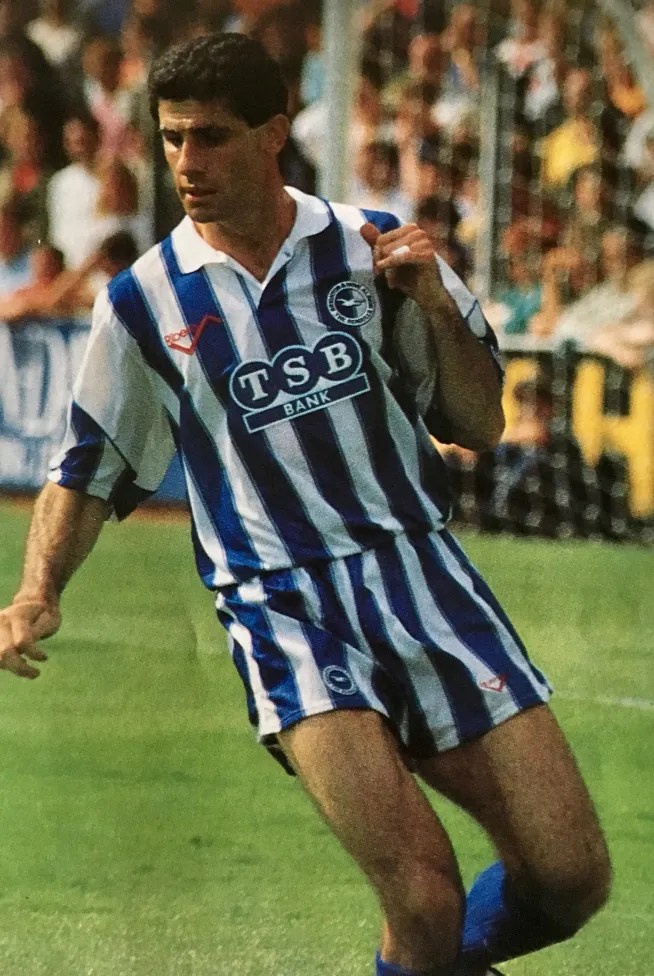

In the summer of 1991, aged 30, he returned to a Brighton side under Barry Lloyd who’d lost the second-tier play-off final to Notts County and once again had to sell players to balance the books. And in that Argus interview he recalled: “Again I took a pay cut, but I had no worries about coming back. I wasn’t concerned about any element of forgiveness although there were a few who would voice their opinion of my former club, which wasn’t very intelligent.”

He made 31 appearances in the 1991-92 season but played his last game on 29 February 1992 sustaining an injury to his right knee against Southend at the Goldstone which ended his career. Albion were subsequently relegated back to the third tier and after a series of unsuccessful knee operations, O’Reilly was forced to retire from the game in April 1993.

He didn’t let the grass grow under his feet, though. While he was still hopeful of regaining his fitness, he joined BBC Radio Sussex to do analysis on Albion games. It wasn’t his first experience at the mic either. When he was not playing at Palace, he sat alongside Jonathan Pearce and did summarising for Capital Radio.

“Doing this work has kept me involved with the game,” he said. “It is much better to concentrate when watching as a reporter. I find that when I just go along as a spectator my mind wanders and that really is frustrating. Broadcasting really must be the next best thing to playing.”

Born in Isleworth on 21 March 1961, O’Reilly grew up in Essex: his parents, Gerry and Mary, having moved to Harlow. His education began at Latton Green Primary School in Harlow and he moved on to Latton Bush Comprehensive, where he stayed on to take his A levels.

Throughout those schooldays he was a promising central defender and he started to make a name for himself with the Essex Boys team. As a schoolboy, he played for both England and the Republic of Ireland because his father was from Dublin and his mother English. He played for the England under-19 schoolboys’ side for two years.

Earlier in his teens, Arsenal wanted him on associate schoolboy forms, but it was Spurs who snapped him up at the age of 13 and during his last two years at school he played as an amateur at Tottenham. His youth team-mates at White Hart Lane included Kerry Dixon and Micky Hazard.

O’Reilly had the offer of a sports scholarship at Columbia University but he decided to sign for Spurs as a professional in the summer of 1979.

His debut aged 19 was on Boxing Day 1980 as a half-time substitute for Chris Hughton in a remarkable 4-4 draw with high-flying Southampton at White Hart Lane. Among a total of 45 first-team appearances in five seasons at Tottenham were games in the Charity Shield at Wembley in 1982 against Liverpool (Spurs lost 1-0) and a quarter-final victory in the UEFA Cup over German giants Bayern Munich.

It was the arrival of Gary Stevens from Albion shortly after the 1983 FA Cup Final that began to signal the end of his time at White Hart Lane, together with the emergence of Danny Thomas.

After hanging up his boots, O’Reilly scouted for Bruce Rioch when he was boss at Bolton Wanderers and spent nine years identifying talent for kit supplier Adidas.

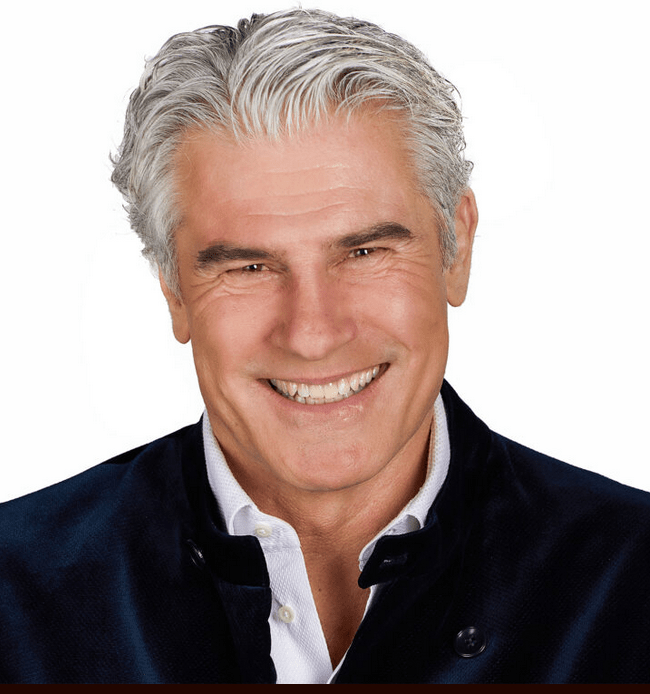

Alongside that, he began a successful broadcasting career which saw him on screen for Meridian, Sky Sports, BBC, Premier League Productions, NBC, Fox Sports and ESPN.

His broadcasting work also extended to India, ART Prime in Dubai and Trans World International’s Premier League international feed.

After marrying in Arundel Cathedral, O’Reilly first lived in Crawley, from where he commuted to Croydon during the Palace years, and later moved to Hove. He subsequently moved to New York where, since 2017, he co-hosts a weekly podcast Playing With Science with Neil deGrasse Tyson for media company StarTalk, exploring fascinating topics linking sport and science.

Anyone unsure in which camp O’Reilly’s heart belongs, he answered diplomatically in a matchday programme interview: “Spurs. It’s always been them, ever since I was six. And I learned so much about the game just by being involved there, especially through (former Spurs captain) Steve Perryman.

“He was always such a believer in doing things the right way. He gave time to any young players. There was none of that “Do you know who I am son?’ None of it at all.”

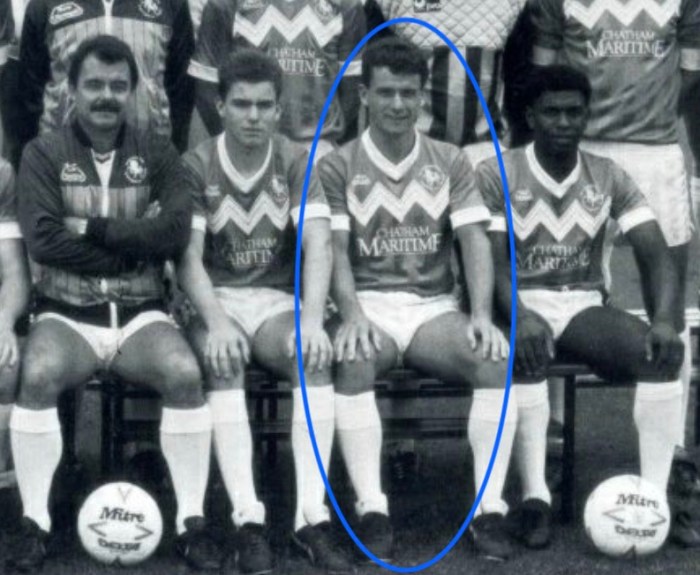

The following two years, he went to play in America for Memphis Rogues (pictured left) where his teammates were players from the English game winding down their careers: the likes of former Albion players

The following two years, he went to play in America for Memphis Rogues (pictured left) where his teammates were players from the English game winding down their careers: the likes of former Albion players