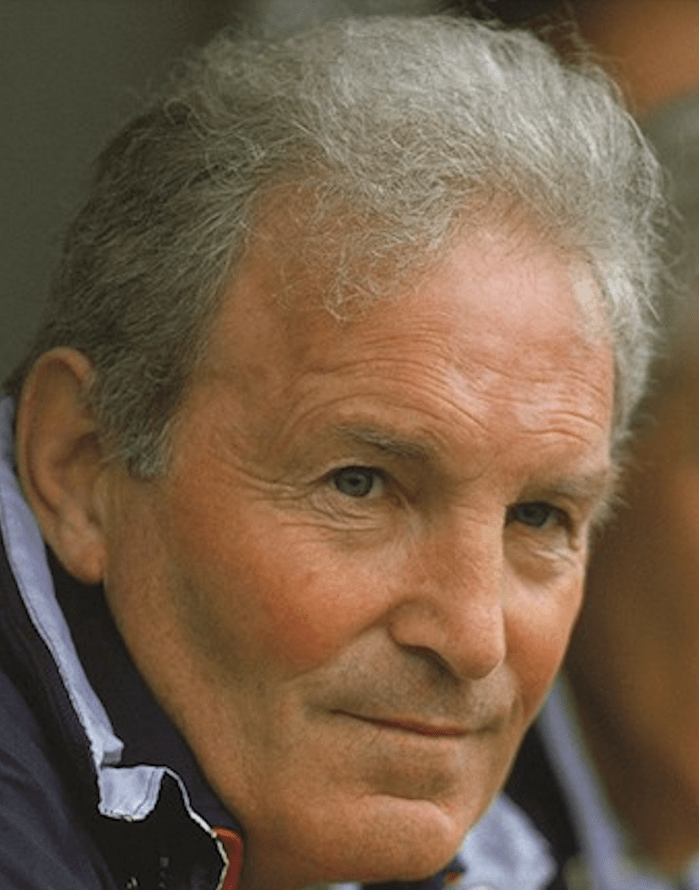

ALTHOUGH I wasn’t even born when Dave Sexton was winning promotion with Brighton, I remember him well as a respected coach and manager.

The record books and plenty of articles have revealed Sexton scored 28 goals in 53 appearances for Brighton before injury curtailed his playing career.

As a manager, he took both Manchester United and Queens Park Rangers to runners-up spot in the equivalent of today’s Premier League and won the FA Cup and European Cup Winners’ Cup with Chelsea.

On top of those achievements, he was the manager of England’s under 21 international side when they won the European Championship in 1982 and 1984, and worked with the full international squad under Ron Greenwood, Bobby Robson, Terry Venables, Glenn Hoddle, Kevin Keegan and Sven-Göran Eriksson.

On his death aged 82 on 25 November 2012, Albion chief executive Paul Barber said: “I know Dave was an extremely popular player during his days at the Goldstone Ground and, as a friend and colleague during my time working at the FA, I can tell you that he was held in equally high esteem.

“He was a football man through and through. I enjoyed listening to many of Dave’s football stories and tales during our numerous hotel stays with the England teams and what always came through was his great love and passion for the game.

“Dave was a true gentleman and a thoroughly nice man.”

Former West Ham and England international, Sir Trevor Brooking, who worked as the FA’s director of football development, said: “Anyone who was ever coached by Dave would be able to tell you what a good man he was, but not only that, what a great coach in particular he was.

“In the last 30-40 years Dave’s name was up there with any of the top coaches we have produced in England – the likes of Terry Venables, Don Howe and Ron Greenwood. His coaching was revered.”

Keith Weller, a £100,000 signing by Sexton for Chelsea in 1970, said: “I had heard all about Dave’s coaching ability before I joined Chelsea and now I know that everything said about his knowledge of the game is true. He has certainly made a tremendous difference to me.”

And the late Peter Bonetti, a goalkeeper under Sexton at Chelsea, said: “He was fantastic, I’ve got nothing but praise for him.”

One-time England captain Gerry Francis, who played for Sexton at QPR and Coventry City, said: “Dave was quite a quiet man. You wouldn’t want to rub him up the wrong way given his boxing family ties, but you wanted to play for him.

“Dave was very much ahead of his time as a manager. He went to Europe on so many occasions to watch the Dutch and the Germans at the time, who were into rotation, and he brought that into our team at QPR, where a full-back would push on and someone would fill in.

“He was always very forward-thinking – a very adaptable manager.”

Guardian writer Gavin McOwan described Sexton as “the antithesis of the outspoken, larger-than-life football manager. A modest and cerebral man, he was one of the most influential and progressive coaches of his generation and brought tremendous success to the two London clubs he managed.”

Born in Islington on 6 April 1930, the son of middleweight boxing champion Archie Sexton, his secondary school days were spent at St Ignatius College in Enfield and he had a trial with West Ham at 15. But, like his dad, he was a boxer of some distinction himself, earning a regional champion title while on National Service.

However, it was football to which he was drawn and, after starting out in non-league with Newmarket Town and Chelmsford City, he joined Luton Town in 1952 and a year later he returned to West Ham, where he stayed for three seasons.

In 77 league and FA Cup games for the Hammers, he scored 29 goals, including hat-tricks against Rotherham and Plymouth.

It was during his time at West Ham that he began his interest in coaching alongside a remarkable group of players who all went on to become successful coaches and managers.

He, Malcolm Allison, Noel Cantwell, John Bond, Frank O’Farrell, Jimmy Andrews and Malcolm Musgrove used to spend hours discussing tactics in Cassettari’s Cafe near the Boleyn ground. A picture of a 1971 reunion of their get-togethers featured on the back page of the Winter 2024 edition of Back Pass, the superb retro football magazine.

One of the game’s most respected managers, Alec Stock, signed Sexton for Orient but he had only been there for 15 months (scoring four goals in 24 league appearances) before moving to Brighton (after Stock had left the Os to take over at Roma).

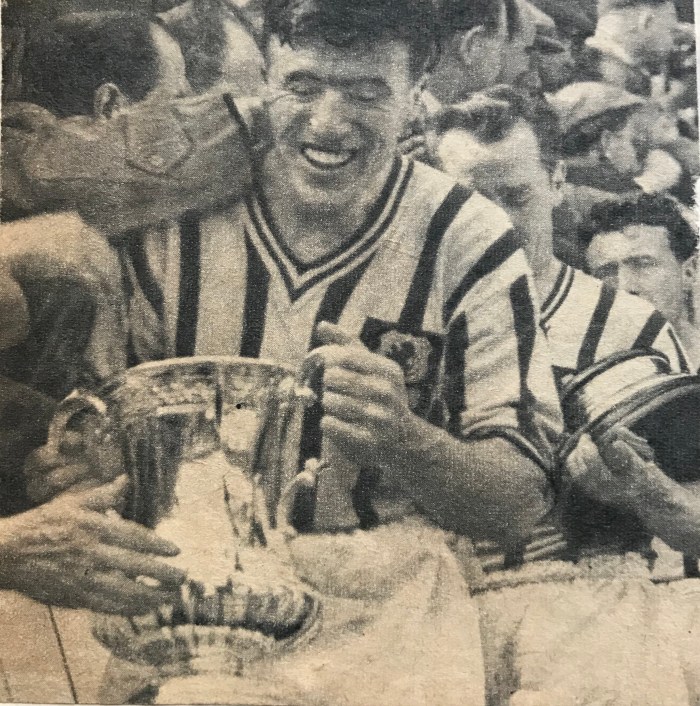

Albion manager Billy Lane bought him for £2,000 in October 1957, taking over Denis Foreman’s inside-left position. Sexton repaid Lane’s faith by scoring 20 goals in 26 league and cup appearances in 1957-58 as Brighton won the old Third Division (South) title. But a knee injury sustained at Port Vale four games from the end of the season meant he missed the promotion run-in. Adrian Thorne took over and famously scored five in the Goldstone game against Watford that clinched promotion.

Nevertheless, as he told Andy Heryet in a matchday programme article: “The Championship medal was the only one that I won in my playing career, so it was definitely the high point.

“All the players got on well, but a lot of what we achieved stemmed from the manager’s approach. It was a real eye-opener for me. We were a free-scoring, very attacking side and I just seemed to fit in right away and got quite a few goals. It was a joy to play with the guys that were there and I thoroughly enjoyed those two years.”

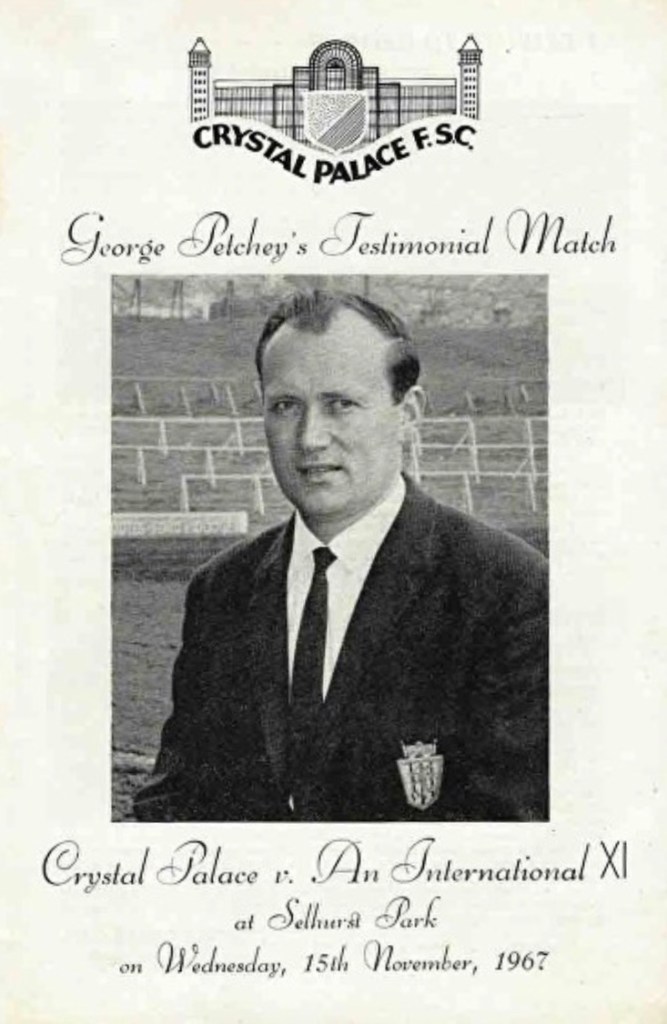

Because of the ongoing problems with his knee, he left Brighton and dropped two divisions to play for Crystal Palace, but he was only able to play a dozen games before his knee finally gave out.

“I suffered with my knee throughout my playing career,” said Sexton. “In only my second league game for Luton I went into a tackle and tore the ligaments in my right knee.

“I also had to have a cartilage removed. The same knee went again when I was at Palace. We were playing away at Northampton, and I went up with the goalkeeper for a cross and landed awkwardly, my leg buckling underneath me, and that sort of finished it off.”

In anticipation of having to retire from playing, he had begun taking coaching courses at Lilleshall during the summer months. Fellow students there included Tommy Docherty and Bertie Mee, both of whom gave him coaching roles after he’d been forced to quit playing.

Docherty stepped forward first having just taken over as Chelsea manager in 1961, appointing Sexton an assistant coach in February 1962. “I didn’t have anything else in mind – I couldn’t play football any more – so I jumped at the chance,” said Sexton. “It was a wonderful bit of luck for me as it meant that my first job was coaching some brilliant players like Terry Venables.”

The Blues won promotion back to the top flight in Sexton’s first full season and he stayed at Stamford Bridge until January 1965, when he was presented with his first chance to be a manager in his own right by his former club Orient.

Frustrated by being unable to shift them from bottom spot of the old Second Division, Sexton quit after 11 months at Brisbane Road and moved on to Fulham to coach under Vic Buckingham, who later gave Johan Cruyff his debut at Ajax and also managed Barcelona.

Perhaps surprisingly, Sexton declared in 1993 that the thing he was most proud of in his career was the six months he spent at Fulham in 1965. “Fulham were bottom of the First Division. Vic Buckingham was the manager. He had George Cohen, Johnny Haynes . . . Bobby Robson was the captain. Allan Clarke came. Good players, but they were bottom of the table, with 13 games to go.

“I did exactly the same things I’d been doing at Orient. And we won nine of those games, drew two and lost two – and stayed up. It proved to me that you can recover any situation, if the spirit is there.”

When Arsenal physiotherapist Mee succeeded Billy Wright as Gunners manager in 1966, he turned to Sexton to join him as first-team coach. In his one full season there, Arsenal finished seventh in the league and top scorer was George Graham, a player the Gunners had brought in from Chelsea as part of a swap deal with Tommy Baldwin.

When the ebullient Docherty parted company with Chelsea in October 1967, Sexton returned to Stamford Bridge in the manager’s chair and enjoyed a seven-year stay which included those two cup wins.

In a detailed appreciation of him on chelseafc.com, they remembered: “Uniquely, for the time, Sexton brought science and philosophy to football: he read French poetry, watched foreign football endlessly and introduced film footage to coaching sessions.”

In those days Chelsea’s side had a blend of maverick talent in the likes of centre forward Peter Osgood and, later, skilful midfielder Alan Hudson. No-nonsense, tough tackling Ron “Chopper” Harris and Scottish full-back Eddie McCreadie were in defence.

As Guardian writer McOwan said: “Sexton was embraced by players and supporters for advocating a mixture of neat passing and attacking flair backed up with steely ball-winners.”

I was taken as a young lad to watch the 1970 FA Cup Final at Wembley when Sexton’s Chelsea drew 2-2 with Leeds United on a dreadful pitch where the Horse of the Year Show had taken place only a few days earlier.

Chelsea had finished third in the league – two points behind Leeds – and while I was disappointed not to see the trophy raised at Wembley (no penalty deciders in those days), the Londoners went on to lift it after an ill-tempered replay at Old Trafford watched by 28 million people on television.

Sexton added to the Stamford Bridge trophy cabinet the following season when Chelsea won the European Cup Winners’ Cup final against Real Madrid, again after a replay.

But when they reached the League Cup final the following season, they lost to Stoke City and it was said Sexton began to lose patience with the playboy lifestyle of people like Osgood and Hudson, who he eventually sold.

The financial drain of stadium redevelopment, and the fact that the replacements for the stars he sold failed to shine, eventually brought about his departure from the club in October 1974 after a bad start to the 1974-75 season.

He was not out of work for long, though, because 13 days after he left Chelsea he succeeded Gordon Jago at Loftus Road and took charge of a QPR side that had some exciting talent of its own in the shape of Gerry Francis and Stan Bowles.

Although the aforementioned Venables had just left QPR to work under Sexton’s old Hammers teammate Allison at Crystal Palace, Sexton brought in 29-year-old Don Masson from Notts County and he quickly impressed with his range of passing, and would go on to be selected for Scotland. Arsenal’s former Double-winning captain Frank McLintock was already in defence and Sexton added two of his former Chelsea players in John Hollins and David Webb.

Sexton said of them: “The easiest team I ever had to manage because they were already mature . . . very responsible, very receptive, full of good characters and good skills. They were coming to the end of their careers, but they were still keen.”

Sexton was a student of Rinus Michels and so-called Dutch ‘total football’ – a fluid, technical system in which all outfield players could switch positions quickly to maximise space on the field.

Loft For Words columnist ‘Roller’ said: “Dave Sexton was decades ahead of his time as a coach. At every possible opportunity he would go and watch matches in Europe returning with new ideas to put into practice with his ever willing players at QPR giving rise to a team that would have graced the Dutch league that he so admired.

“He managed to infuse the skill and technique that is a hallmark of the Dutch game into the work ethic and determination that typified the best English teams of those times.

“QPR’s passing and movement was unparalleled in the English league and wouldn’t been seen again until foreign coaches started to permeate into English football.”

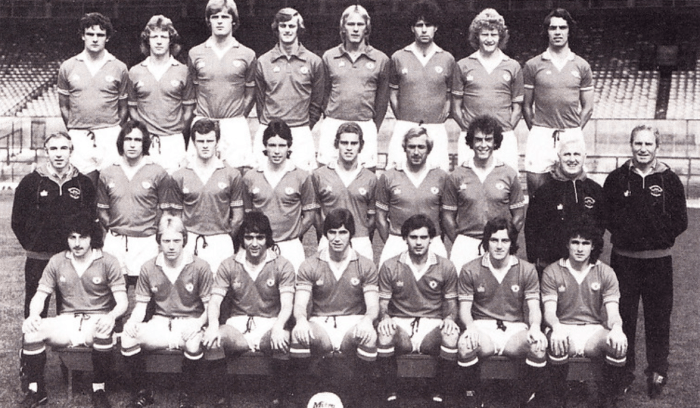

His second season at QPR (1975-76) was the most successful in that club’s history and they were only pipped to the league title by Liverpool (by one point) on the last day of the season (Man Utd were third).

Agonisingly Rangers were a point ahead of the Merseysiders after the Hoops completed their 42-game programme but had to wait 10 days for Liverpool to play their remaining fixture against Wolves who were in the lead with 15 minutes left but then conceded three, enabling Liverpool to clinch the title.

Married to Thea, the couple had four children – Ann, David, Michael and Chris – and throughout his time working in London the family home remained in Hove, to where he’d moved in 1958. They only upped sticks and moved to the north when Sexton landed the Man Utd job in October 1977.

He once again found himself replacing Docherty, who had been sacked after his affair with the wife of the club’s physiotherapist had been made public.

It was said by comparison to the outspoken Docherty, Sexton’s measured, quiet approach didn’t fit well with such a high profile club which then, as now, was constantly under the media spotlight.

The press dubbed him ‘Whispering Dave’ and although some signings, like Ray Wilkins, Gordon McQueen and Joe Jordan, were successful, he was ridiculed for buying striker Garry Birtles for £1.25m from Nottingham Forest: it took Birtles 11 months to score his first league goal for United.

Sexton took charge of 201 games across four years (with a 40 per cent win ratio) and he steered United to runners-up spot in the equivalent of the Premier League, two points behind champions Liverpool, in the 1979-80 season. United were also runners-up in the 1979 FA Cup final, losing 3-2 to a Liam Brady-inspired Arsenal.

As he said in a subsequent interview: “I really enjoyed my time at United. You are treated like a god up there and the support is fantastic. I had mixed success but it’s something that I wouldn’t have missed for the world.

“It’s tough at the top however and while other clubs would have been quite happy in finishing runners-up, it wasn’t enough for Man Utd. That’s the name of the game and I bear no grudges over it at all.”

As it happens, Sexton’s successor Ron Atkinson only managed to take United to third in the league (although they won the FA Cup twice) and it was another seven seasons before they were runners-up again under Alex Ferguson’s stewardship.

But back in 1981, United’s loss was Coventry’s gain and their delight at his appointment was conveyed in an excellent detailed profile by Rob Mason in 2019.

“By the time the name of Dave Sexton was being put on the door of the manager’s office at Highfield Road the gaffer was in his fifties and a highly regarded figure within the game,” wrote Mason. “That sprang from the style of pass and move football he liked to play. His was a cultured approach to the game and Coventry supporters could look forward to seeing some attractive football.”

One of the happy quirks of football saw his old employer take on his new one on the opening day of the 1981-82 season – and the Sky Blues won 2-1! They won by a single goal at Old Trafford that season too, but overall away form was disappointing and in spite of a strong finish (seven wins, four draws and one defeat) they finished 14th – a modest two-place improvement on the previous season.

On a limited budget, Sexton struggled to get a largely young squad to make too much progress but he did recruit former England captain Gerry Francis, who’d been his captain during heady days at QPR, and he was a good influence on the youngsters.

Sexton’s second season in charge began well but ended nearly disastrously with a run of defeats leaving them flirting with relegation, together with Brighton. One of his last league games as City manager was in the visitors’ dugout at the Goldstone. Albion beat the Sky Blues 1-0 courtesy of a Terry Connor goal on St George’s Day 1983 – but it was Sexton’s side who escaped the drop by a point. Albion didn’t.

Coventry’s narrow escape from relegation cost Sexton his job (although he remained living in Kenilworth, Warwickshire) and it proved to be his last as a club manager, although he was involved as a coach when Ron Atkinson’s Aston Villa finished runners up in the first season (1992-93) of the Premier League – behind Ferguson’s United, who won their first title since 1967.

Villa beat United at home and nicked a point at Old Trafford and ahead of the drawn game Richard Williams of The Independent dropped in on a Villa training session to interview Sexton.

Sexton was happy to be working with the youth team, the young pros and the first team. “Mostly I’ve been concerned with movement, up front and in midfield. Instead of the traditional long ball up to the front men, approaching the goal in not such straight lines,” he explained.

The quiet Sexton had a valid retort to the reporter’s surprise that he should be working in the same set-up as the flamboyant Atkinson. “It’s like most stereotypes,” he said. “They’re never quite as they seem to be. Ron’s got a flamboyant image, but actually he’s an idealist, from a football point of view.

“He’s got a vision, which might not come across from the stereotype he’s got. I suppose it’s the same with me. I’m meant to be serious, which I am, but I like a bit of fun, too. And, obviously, the thing we’ve got in common is a love of football.”

Relieved to be more in the background than having to be the front man, Sexton told Williams: “The reason I’m in the game in the first place is that I love football and working with footballers, trying to improve them individually and as a team.

“So, to shed the responsibility of speaking to the press and the directors and talking about contracts, it’s a weight off your shoulders. Now I’m having all the fun without any of the hassle.”

Atkinson had invited his United predecessor to join him at Villa after he had retired from his job as the FA’s technical director of the School of Excellence at Lilleshall, and coach of the England under 21 team.

It had been 10 years since Bobby Robson had appointed him as assistant manager to the England team (Sexton had coached Robson at Fulham). He had previously been involved coaching England under 21s alongside his club commitments since 1977 leading the side to back-to-back European titles in 1982 and 1984. The 1982 side, who beat West Germany 5-4 on aggregate over two legs, included Justin Fashanu and Sammy Lee, and in a quarter final v Poland he had selected Albion’s Andy Ritchie, somewhat ironically considering he had sold him to the Seagulls when manager at United.

In April 1983, Albion’s Gary Stevens played for Sexton’s under 21s in a European Championship qualifier at Newcastle’s St James’ Park, which was won 1-0. The following year, Stevens, by then with Spurs, was in the side that met Spain in the final, featuring in the first of the two legs, a 1-0 away win in Seville. Somewhat confusingly, his Everton namesake featured in the second leg, a 2-0 win at Bramall Lane. England won 3-0 on aggregate. Winger Mark Chamberlain, later an Albion player, also played in the first leg.

After the Robson era, Sexton worked with successive England managers: Venables, Hoddle and Keegan. When Eriksson became England manager in 2001, he invited Sexton to run a team of scouts who would compile a database and video library of opposition players – a strategy Sexton had pioneered three decades previously.

Viewed as one of English football’s great thinkers, Sexton had a book, Tackle Soccer, published in 1977 but away from football he had a love of art and poetry and completed an Open University degree in philosophy, literature, art and architecture. He was awarded an OBE for services to football in 2005.

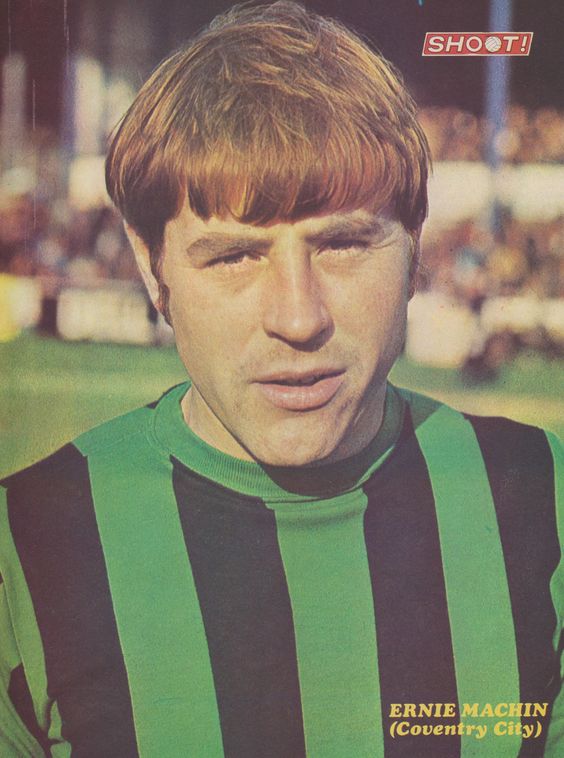

A MIDFIELD dynamo who captained Coventry City during their glory years at the top of English football’s pyramid was instantly installed as captain when he signed for third tier Brighton.

A MIDFIELD dynamo who captained Coventry City during their glory years at the top of English football’s pyramid was instantly installed as captain when he signed for third tier Brighton. The midfielder eventually completed 31 games (plus three as sub) but manager Taylor took the captaincy from him and appointed his new centre back signing,

The midfielder eventually completed 31 games (plus three as sub) but manager Taylor took the captaincy from him and appointed his new centre back signing,  Machin played 41 games that season and only shared the midfield with Horton once – in what turned out to be his final game in the stripes, a 4-2 home win over Grimsby Town.

Machin played 41 games that season and only shared the midfield with Horton once – in what turned out to be his final game in the stripes, a 4-2 home win over Grimsby Town. Machin was a member of the Coventry City Former Players Association after his career ended and they paid due respect to his part in the club’s history when he died aged 68 on 22 July 2012.

Machin was a member of the Coventry City Former Players Association after his career ended and they paid due respect to his part in the club’s history when he died aged 68 on 22 July 2012.

A CULTURED midfielder regarded in many circles as the best ever captain of Aston Villa was almost ever-present in one season with Brighton.

A CULTURED midfielder regarded in many circles as the best ever captain of Aston Villa was almost ever-present in one season with Brighton.

Knowing his time on the south coast was going to be limited, Mortimer didn’t uproot his family from their Lichfield home and instead lived in the Courtlands Hotel in Hove (above) for a while and also bought a flat where his wife and children could visit during school holidays.

Knowing his time on the south coast was going to be limited, Mortimer didn’t uproot his family from their Lichfield home and instead lived in the Courtlands Hotel in Hove (above) for a while and also bought a flat where his wife and children could visit during school holidays.

IT MUST BE difficult for today’s reader to imagine a player with the opportunity to sign for either Coventry City or Chelsea choosing the Sky Blues over the London giants.

IT MUST BE difficult for today’s reader to imagine a player with the opportunity to sign for either Coventry City or Chelsea choosing the Sky Blues over the London giants.