DEVONIAN FRED BINNEY was a prolific goalscorer for Brighton but the emergence of one of the club’s all-time great players brought a premature end to his stay in Sussex.

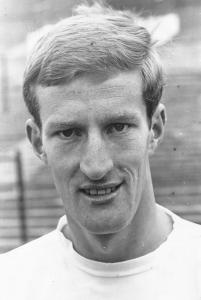

Binney was not afraid to put a head or boot in where it hurt and black and white action photographs in matchday programmes from the 1974-75 and 1975-76 seasons and in the Evening Argus invariably featured goalmouth action involving the moustachioed or bearded Binney.

I particularly remember a shot of him continuing to play wearing a bloodied head bandage after he’d cut himself but played on in a home game against Hereford United, a club he later played for and coached.

The ‘old school’ centre forward was signed by Brian Clough and Peter Taylor from Exeter City at the end of the 1973-74 season in exchange for Lammie Robertson and John Templeman plus £25,000.

Taylor had sought the opinion of David Pleat, later a manager of Luton, Tottenham and Leicester, who had played alongside Binney for the Grecians.

Pleat recalls in the Summer 2025 edition of Backpass magazine: “I told him that he was a clinical finisher, very sharp, had an eye for goal but tended to be caught offside too often.”

Incidentally, Templeman, a Sussex lad who had been an Albion player for eight years, didn’t want to leave but, as he told Spencer Vignes in his book Bloody Southerners (Biteback Publishing 2018), Taylor told him he’d never play league football again if he didn’t agree to the move.

Binney’s arrival came as the former league title-winning duo set about clearing out most of the squad they inherited from Pat Saward as they sought to rebuild. Around the same time, a triple signing from Norwich City saw Ian Mellor, Andy Rollings and Steve Govier arrive.

Clough clearly didn’t fancy the forwards Saward had signed and, as well as using Robertson as a makeweight also let go two previous record signings in Ken Beamish and Barry Bridges.

Binney hadn’t managed to kick a ball in anger for Clough before the outspoken boss left to manage Leeds, but sidekick Taylor felt he owed it to chairman Mike Bamber to stay, and took on the job alone (bringing in ex-Long Eaton manager Brian Daykin as his no.2).

Taylor also recruited Ricky Marlowe, a youngster who’d been a reserve at their old club, Derby County, to play up front with Binney, along with several other new arrivals with past Rams connections, such as Jim Walker and Tommy Mason.

It was not really surprising they thought Binney could do a job for Brighton because in 1972-73 he had scored 28 league goals for Exeter, making him the season’s joint-top goal scorer in the entire Football League (along with West Ham’s Bryan Robson). And in 1973-74, he was voted the PFA Division Four Player of the Year and Exeter City Player of the Year after he’d scored another 30 league and cup goals.

It was said the Grecians had already turned down an offer from Swindon Town before he made the move to Sussex.

With so many new arrivals at the Goldstone, perhaps, not surprisingly, consistency was hard to find in the 1974-75 campaign and Binney didn’t come close to repeating that scoring form with only 13 goals to his name as Albion finished a disappointing 19th in the table.

That all changed in 1975-76 – Albion’s 75th anniversary season – and Binney was on fire, netting 23 goals as Albion narrowly missed out on promotion. Taylor still couldn’t resist chopping and changing Binney’s strike partners. He started out with new arrival Neil Martin, an experienced Scottish international, then had Nottingham Forest loanee Barry Butlin.

When craggy Northern Irish international Sammy Morgan arrived from Aston Villa, it looked like Taylor had finally found his ideal pair, although it took Morgan six matches before he struck a rich vein of form.

Meanwhile a young reserve who’d been blooded in a friendly against First Division Ipswich Town on Friday 13th February 1976 began to find himself included in the first team picture.

He’d been a non-playing substitute three times before a big top-of-the-table clash away to leaders Hereford on 27 March, which BBC’s Match of the Day had chosen to cover.

In the pre-match team meeting, manager Taylor announced that Binney wouldn’t be playing and that Peter Ward would take his place.

“Fred Binney was nice, a great fella; there was no friction between us and I didn’t really have time to think about how he was feeling,” Ward said in Matthew Horner’s 2009 book about him (He Shot, He Scored, Sea View Media).

Just 50 seconds into the game, Ward scored, the game finished 1-1 – but Ward didn’t look back and went on to become one of the club’s greatest ever players.

Binney wasn’t quite finished but it was the beginning of the end. Ward scored again in his second match as Binney’s replacement (another 1-1 draw, at Rotherham) but after a 2-1 defeat at Chesterfield, Binney was restored to the starting line-up in place of Morgan and opened the scoring in a 3-0 home win over Port Vale (Ward and Mellor also scored).

Sadly, it was Albion’s last win of the season. They lost 3-1 away to promotion rivals Millwall and drew the last three games resulting in them finishing fourth, three points off the promotion spots.

Binney scored a consolation goal in that game at The Den but ended up having to make his own way home when fuming Taylor ordered the team coach driver to leave without him!

Ward recounted the story in Horner’s book: “Pete Taylor had just had a real go at us in the changing rooms and we were all sitting in silence on the coach, wanting to get home as soon as we could.

“Fred was the only one still not on the bus because he was standing around talking to someone. Pete wouldn’t wait and said to the bus driver, ‘F••• him. Leave him. Let’s go’. It wasn’t the sort of place at which you’d want to be left but, luckily for Fred, he got a lift from some fans and managed to get back to Brighton before the coach.”

In his review of the season for the Argus, John Vinicombe wrote: “Few forwards in the division could match Fred Binney for converting half chances into goals,” although he observed that only eight of his goals were scored away from the Goldstone. “Away from home, Binney did not fit into the tactical plan. He looked lost,” wrote Vinicombe.

While the team missed out on promotion because of those draws, young Ward enhanced his credentials by scoring the equaliser in each of them, taking his tally to six goals in eight games.

Taylor decided to team up with Clough once again, at Nottingham Forest, and disappointed chairman Mike Bamber turned to former Spurs captain Alan Mullery who had thought he was going to take charge of Fulham after retiring from playing but was spurned in favour of Bobby Campbell.

As he assessed the strengths and weaknesses of his squad in pre-season training, Mullery quickly took a liking to Ward and gave Binney short shrift when he tried to persuade him that picking the youngster instead of him would get him the sack.

Even so Binney started the first ten games of the 1976-77 season, and scored four goals, but he was subbed off in favour of Gerry Fell on 50 minutes of the September home game v York City when the score was 2-2 and suddenly the floodgates opened with Albion scoring five without reply in front of the Match of the Day cameras. Binney didn’t play another game for the first team.

In the days of only one substitute, invariably it was his old strike partner Morgan who got the seat on the bench. In his autobiography, Mullery wrongly recollects that he sold Binney to Exeter within two months. While there were plenty of rumours of Binney moving on, with Torquay, Reading, Crystal Palace and Gillingham all keen to sign him, he spent the rest of the season turning out for Albion reserves.

“One of the best goalscorers in the lower divisions and popular with the Albion supporters, Binney was perhaps the biggest victim of Ward’s stunning introduction to league football,” Horner observed, noting that in 15 games in which they played together, that Vale game was the only match when they both scored.

Binney left Brighton having scored an impressive 35 goals in 70 matches and, as was often the case at that time, a chance to play in America would prove to be a blessing for him.

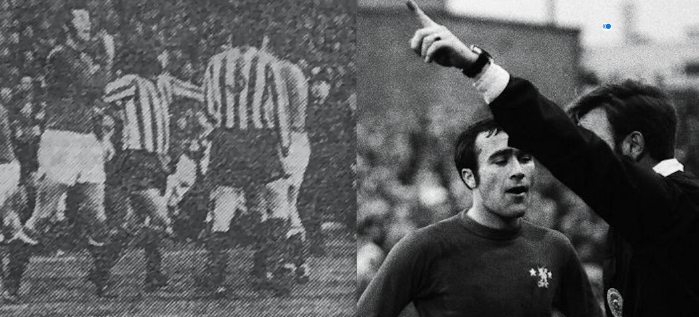

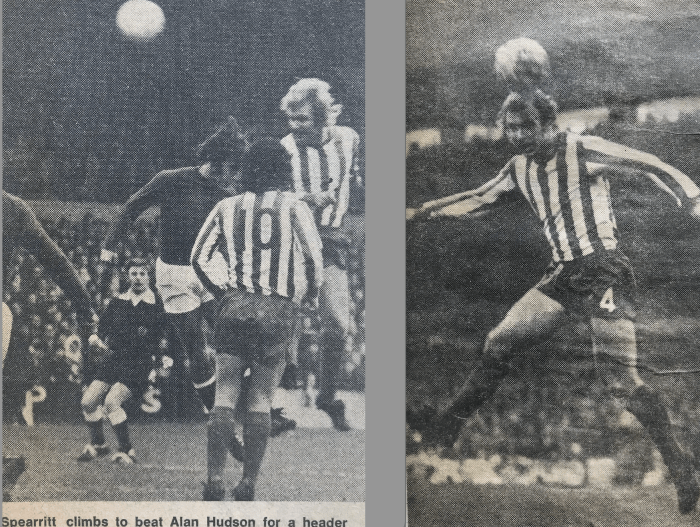

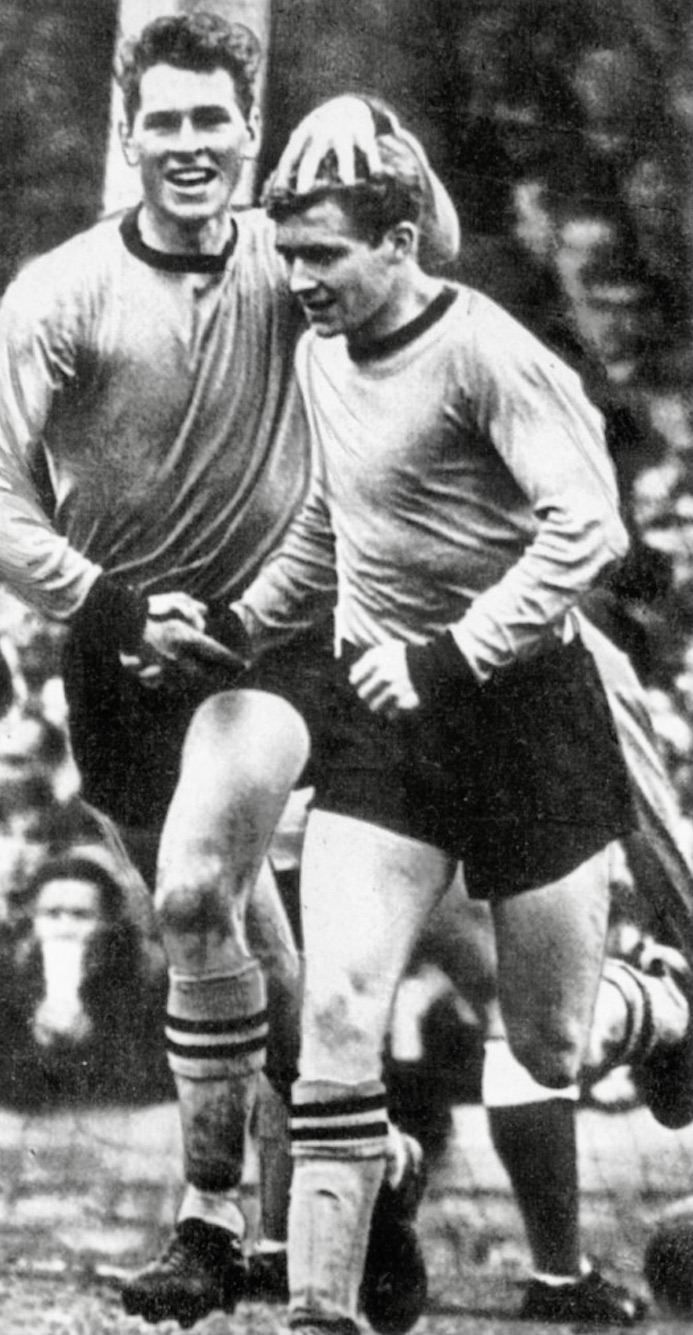

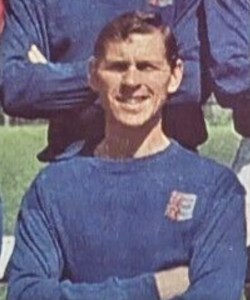

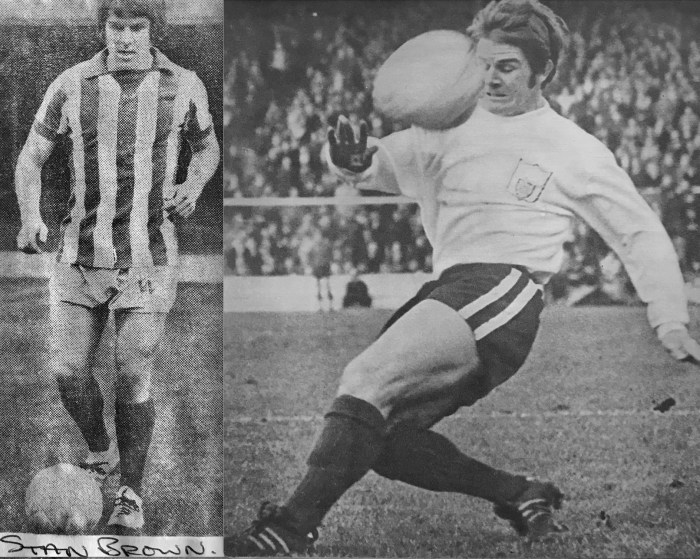

Binney up against Welsh international Mike England, left for Albion v Cardiff, right for St Louis Stars

He joined Missouri-based St. Louis Stars in the North American Soccer League, who had John Jackson in goal and former Spurs player Ray Evans in defence along with ex-Albion defender Dennis Burnett and ex-Palace and Liverpool full-back Peter Wall.

In a side managed by ex-Palace and Orient player John Sewell, Binney kept up his impressive scoring record by bagging nine goals in 18 appearances. Fellow striker Barry Salvage, who’d played for the likes of Fulham, QPR, Brentford and Millwall, only scored once in 25 games.

Born in Plymouth on 12 August 1946, it was to his hometown club that he moved on his return to the UK from America.

Binney had been raised in the Barbican area of Plymouth and I am grateful to Ian De-Lar of Vital Argyle for filling in details of his early playing career.

He was a prolific goalscorer in junior football whilst playing for CM Department juniors and was signed by South Western League side Launceston.

While starting work as an apprentice at Devonport Dockyard, he also played for John Conway in the Devon Wednesday League, where he was spotted by Torquay United scout Don Mills.

Torquay took him on as an amateur before he signed a professional contract in October 1966. Although he made his first team debut in September 1967, he was mainly a reserve team player and went on loan to Exeter City in February 1969 before joining them on a permanent basis in March 1970 for £4,000.

He’d scored 11 goals in 24 starts for the Gulls but in view of his future success Torbay Weekly reporter Dave Thomas declared: “If there was a ‘One That Got Away’ story from that era, it was surely Fred Binney.

“The bustling, irrepressible Plymothian was snapped up by United as a teenager, but despite hitting the net at will in the reserves, he could never convince (manager Frank) O’Farrell that he was the real deal.”

It was during the brief managerial reign of former goalkeeper Mike Kelly that Binney joined Argyle in October 1977 and although he scored nine in 18 matches, he wasn’t able to hold down a regular starting spot.

But when the wily former Crystal Palace and Manchester City manager Malcolm Allison returned to Home Park as manager, Binney’s fortunes turned round and, in the 1978-79 season, he scored a total of 28 goals, was the team’s leading goalscorer and ‘Player of the Year’.

In Allison’s first away match, on 21 March 1978, he was rewarded for giving Binney his first senior game for 10 weeks when the predatory striker scored twice in a 5-1 win at Fratton Park. Also on the scoresheet was 18-year-old substitute Mike Trusson, who replaced the injured Steve Perrin. Pompey’s consolation was scored by Binney’s former Albion teammate Steve Piper, on as a sub for the home side.

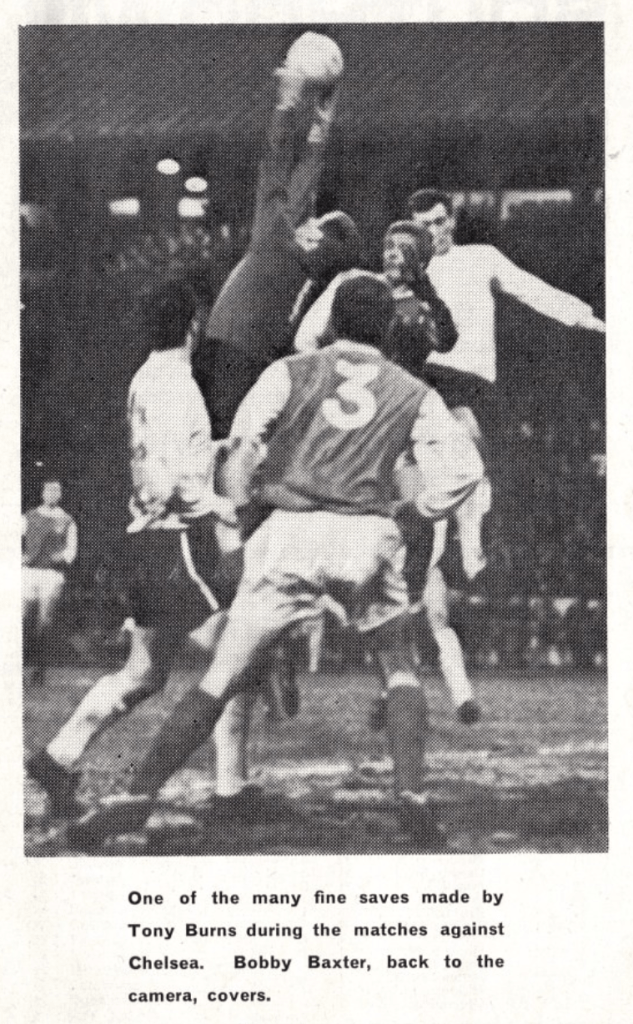

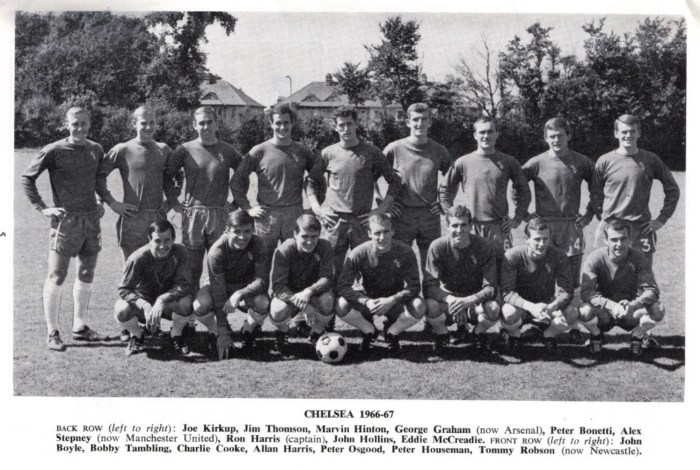

Binney’s goal-every-other-game ratio at Argyle saw him net a total of 42 goals in 81 games – 40 while Allison was his manager. That Argyle squad had Tony Burns as back-up goalkeeper to Martin Hodge.

Those goals helped to earn Binney 20th place in a list of the top 25 ‘Greatest Pilgrims’ voted for in July 2019.

But Allison’s successor, the former Argyle player Bobby Saxton, had different ideas and sold Binney to Hereford United for £37,000 in October 1979.

He scored six times in 27 appearances for the Bulls before moving into coaching, at first becoming assistant manager to Hereford boss Frank Lord. When Lord left in 1982 to manage the Malaysia national team, Binney went too.

He returned to England in 1985 to become assistant manager to Colin Appleton at his old club Exeter. When Appleton was sacked in December 1987, Binney went with him, taking up a role as recreation officer at Plymouth University. He subsequently became president and coach of its football club, and retired in 2013.

That year, Binney’s son Adam was in touch with the excellent The Goldstone Wrap blog, saying of his dad: “He is not really interested in being lauded and doesn’t look for any kind of adoration. He doesn’t really like the attention, but he does love Brighton & Hove Albion and remembers his time there fondly.”

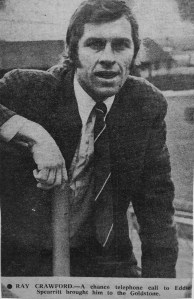

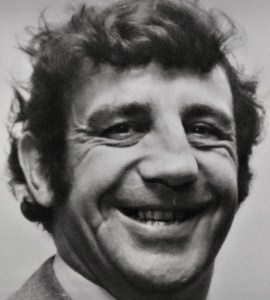

• In the Backpass article (left), Pleat recalls how, during his time as Leicester manager, Binney was his West Country talent scout. He also tells how Binney and his wife Lesley ran a cream tea shop in Modbury, Devon, for many years and how the former striker enjoyed travelling the length and breadth of the country’s canals on his own longboat, Escargot.