FOR 40 YEARS, Mike Bailey was the manager who had led Brighton & Hove Albion to their highest-ever finish in football.

A promotion winner and League Cup-winning captain of Wolverhampton Wanderers, he took the Seagulls to even greater heights than his predecessor, Alan Mullery.

But the fickle nature of football following has remembered Bailey a lot less romantically than the former Spurs, Fulham and England midfielder.

The pragmatic way Brighton played under Bailey turned fans off in their thousands and, because gates dipped significantly, he paid the price.

Finishing 13th in the top tier in 1982 playing a safety-first style of football counted for nothing, even though it represented a marked improvement on relegation near-misses in the previous two seasons under Mullery, delivering along the way away wins against Tottenham Hotspur, Liverpool and then-high-flying Southampton as well as a first-ever victory over Arsenal.

Bailey’s achievement with the Albion was only overtaken in 2022 with a ninth place finish under Graham Potter; since surpassed again with a heady sixth and European qualification under Roberto De Zerbi.

Fascinatingly, though, Bailey had his eyes on Europe as far back as the autumn of 1981 and laid his cards on the table in a forthright article in Shoot! magazine.

“I am an ambitious man,” he said. “I am not content with ensuring that Brighton survive another season at this level. I want people to be surprised when we lose and to omit us from their predictions of which clubs will have a bad season.

“I am an enthusiast about this game. I loved playing, loved the atmosphere of a dressing room, the team spirit, the sense of achievement.

“As a manager I have come to realise there are so many other factors involved. Once they’re on that pitch the players are out of my reach; I am left to gain satisfaction from seeing the things we have worked on together during the week become a reality during a match.

“I like everything to be neat – passing, ball-control, appearance, style. Only when we have become consistent in these areas will Brighton lose, once and for all, the tag of the gutsy little Third Division outfit from the South Coast that did so well to reach the First Division.”

Clearly revelling in finding a manager happy to speak his mind, the magazine declared: “As a player with Charlton, Wolves and England, Bailey gave his all, never hid when things went wrong, accepted responsibility and somehow managed to squeeze that little bit extra from the players around him when his own game was out of tune.

“As a manager he is adopting the same principles of honesty, hard work and high standards of professionalism.

“So, when Bailey sets his jaw and says he wants people to expect Brighton to win trophies, he means that everyone connected with Albion must forget all about feeling delighted with simply being in the First Division.”

Warming to his theme, Bailey told Shoot!: “This club has come a long way in a short time. But now is the time to make another big step…or risk sliding backwards. Too many clubs have done just that – wasted time basking in recent achievements and crashed back to harsh reality.

“I do not intend for us to spend this season simply consolidating. That has been done in the last few seasons.”

If that sounds a bit like Roberto De Zerbi, unfortunately many long-time watchers of the Albion like me would more likely compare the style under Bailey to the pragmatism of the Chris Hughton era: almost a complete opposite to De Zerbi’s free-flowing attacking play.

It was ultimately his downfall because the court of public opinion – namely paying spectators who had rejoiced in a goals galore diet during Albion’s rise from Third to First under Mullery – found the new man’s approach too boring to watch and stopped filing through the turnstiles.

Back in 2013, the superb The Goldstone Wrap blog noted: “Only Liverpool attracted over 20,000 to the Goldstone before Christmas. The return fixture against the Reds in March 1982 was the high noon of Bailey’s spell as Brighton manager.

“A backs-to-the-wall display led to a famous 1-0 win at Anfield against the European Cup holders, with Andy Ritchie getting the decisive goal and Ian Rush’s goalbound shot getting stuck in the mud!”

At that stage, Albion were eighth but a fans forum at the Brighton Centre – and quite possibly a directive from the boardroom – seemed to get to him.

Supporters wanted the team to play a more open, attacking game. The result? Albion recorded ten defeats in the last 14 matches.

At odds with what he had heard, he very pointedly said in his programme notes: “It is my job to select the team and to try to win matches.

“People are quite entitled to their opinion, but I am paid to get results for Brighton and that is my first priority.

“Building a successful team is a long-term business and I have recently spoken to many top people in the professional game who admire what we are doing here at Brighton and just how far we have come in a short space of time.

“We know we still have a long way to go, but we are all working towards a successful future.”

Dropping down to finish 13th of 22 clubs, Albion never regained a spot in the top half of the division and The Goldstone Wrap observed: “If Bailey had stuck to his guns, and not listened to the fans, would the club have enjoyed a UEFA Cup place at the end of 1981-82?”

Bailey certainly wasn’t afraid to share his opinions and, as well as in the Shoot! article, he often vented his feelings quite overtly in his matchday programme notes; hitting out at referees, the football authorities and the media, as well as trying to explain his decisions to supporters, urging them to get behind the team rather than criticise.

It certainly didn’t help that the mercurial Mark Lawrenson was sold at the start of his regime as well as former captain Brian Horton and right-back-cum-midfielder John Gregory, but Bailey addressed the doubters head on.

“I believe it was necessary because while I agree that a player of Lawrenson’s ability, for example, is an exceptional talent, it is not enough to have a handful of assets.

“We must have a strong First Division squad, one where very good players can come in when injuries deplete the side.

“We brought in Tony Grealish from Luton, Don Shanks from QPR, Jimmy Case from Liverpool and Steve Gatting and Sammy Nelson from Arsenal. Now the squad is better balanced. It allows for a permutation of positions and gives adequate cover in most areas.”

One signing Bailey had tried to make that he had to wait a few months to make was one he would come to regret big time. Long-serving Peter O’Sullivan had left the club at the same time as Lawrenson, Horton and Gregory so there was a vacancy to fill on the left side of midfield.

Bailey had his eyes on Manchester United’s Mickey Thomas but the Welsh wideman joined Everton instead. When, after only three months, the player fell out with Goodison boss Howard Kendall, Bailey was finally able to land his man for £350,000 on a four-year contract.

Talented though Thomas undoubtedly was, what the manager didn’t bargain for was the player’s unhappy 20-year-old wife, Debbie.

She was unable to settle in Sussex – the word was that she gave it only five days, living in a property at Telscombe Cliffs – and went back to Colwyn Bay with their baby son.

Thomas meanwhile stayed at the Courtlands Hotel in Hove and the club bent over backwards to give him extra time off so he could travel to and from north Wales. But he began to return late or go missing from training.

After the third occasion he went missing, Bailey was incandescent with rage and declared: ”Thomas has s*** on us….the sooner the boy leaves, the better.”

At one point in March, it was hoped a swap deal could be worked out that would have brought England winger Peter Barnes to the Goldstone from Leeds, but they weren’t interested and so the saga dragged out to the end of the season.

After yet another absence and fine of a fortnight’s wages, Bailey once again went on the front foot and told Argus Albion reporter John Vinicombe: “He came in and trained which allowed him to play for Wales.

“He is just using us, and yet I might have played him against Wolves (third to last game of the season). Thomas is his own worst enemy and I stand by what I’ve said before – the sooner he goes the better.”

Thomas was ‘shop windowed’ in the final two games and during the close season was sold to Stoke City for £200,000.

In his own assessment of his first season, Bailey said: “Many good things have come out of our season. Our early results were encouraging and we quickly became an organised and efficient side. The lads got into their rhythm quickly and it was a nice ‘plus’ to get into a high league position so early on.”

He had special words of praise for Gary Stevens and said: “Although the youngest member of our first team squad, Gary is a perfect example to his fellow professionals. Whatever we ask of him he will always do his best, he is completely dedicated and sets a fine example to his fellow players.”

The biggest bugbear for the people running the club was that the average home gate for 1981-82 was 18,241, fully 6,500 fewer than had supported the side during their first season at the top level.

“The Goldstone regulars grew restless at a series of frustrating home draws, and finally turned on their own players,” wrote Vinicombe in his end of season summary for the Argus.

He also said: “It is Bailey’s chief regret that he changed his playing policy in response to public, and possibly private, pressure with the result that Albion finished the latter part of the season in most disappointing fashion.

“Accusations that Albion were the principal bores of the First Division at home were heaped on Bailey’s head, and, while he is a man not given to altering his mind for no good reason, certain instructions were issued to placate the rising tide of criticisms.”

If Bailey wasn’t exactly Mr Popular with the fans, at the beginning of the following season, off-field matters brought disruption to the playing side.

Steve Foster thought he deserved more money having been to the World Cup with England and he, Michael Robinson and Neil McNab questioned the club’s ambition after chairman Bamber refused to sanction the acquisition of Charlie George, the former Arsenal, Derby and Southampton maverick, who had been on trial pre-season.

Robinson went so far as to accuse the club of “settling for mediocrity” and couldn’t believe Bailey was working without a contract.

Bamber voiced his disgust at Robinson, claiming it was really all about money, and tried to sell him to Sunderland, with Stan Cummins coming in the opposite direction, but it fell through. Efforts were also made to send McNab out on loan which didn’t happen immediately although it did eventually.

All three were left out of the side temporarily although Albion managed to beat Arsenal and Sunderland at home without them. In what was an erratic start to the season, Albion couldn’t buy a win away from home and suffered two 5-0 defeats (against Luton and West Brom) and a 4-0 spanking at Nottingham Forest – all in September.

Other than 20,000 gates for a West Ham league game and a Spurs Milk Cup match, the crowd numbers had slumped to around 10,000. Former favourite Peter Ward was brought back to the club on loan from Nottingham Forest and scored the only goal of the game as Manchester United were beaten at the Goldstone.

But four straight defeats followed and led to the axe for Bailey, with Bamber declaring: “He’s a smashing bloke, I’m sorry to see him go, but it had to be done.”

Perhaps the writing was on the wall when, in his final programme contribution, he blamed the run of poor results simply on bad luck and admitted: “I feel we are somehow in a rut.”

It didn’t help the narrative of his reign that his successor, Jimmy Melia, surfed on a wave of euphoria when taking Albion to their one and only FA Cup Final – even though he also oversaw the side’s fall from the elite.

“It seems that my team has been relegated from the First Division while Melia’s team has reached the Cup Final,” an irked Bailey said in an interview he gave to the News of the World’s Reg Drury in the run-up to the final.

Hurt by some of the media coverage he’d seen since his departure, Bailey resented accusations that his style had been dull and boring football, pointing out: “Nobody said that midway through last season when we were sixth and there was talk of Europe.

“We were organised and disciplined and getting results. John Collins, a great coach, was on the same wavelength as me. We wanted to lay the foundations of lasting success, just like Bill Shankly and Bob Paisley did at Liverpool.

“The only problem was that winning 1-0 and 2-0 didn’t satisfy everybody. I tried to change things too soon – that was a mistake.

“When I left (in December 1982), we were 18th with more than a point a game. I’ve never known a team go down when fifth from bottom.”

Bailey later expanded on the circumstances, lifting the lid on his less than cordial relationship with Bamber, when speaking on a Wolves’ fans forum in 2010. “We had a good side at Brighton and did really well,” he said. “The difficulty I had was with the chairman. He was not satisfied with anything.

“I made Brighton a difficult team to beat. I knew the standard of the players we had and knew how to win matches. We used to work on clean sheets.

“With the previous manager, they hadn’t won away from home very often but we went to Anfield and won. But the chairman kept saying: ‘Why can’t we score a few more goals?’ He didn’t understand it.”

Foster, the player Bailey made Albion captain, was also critical of the ‘boring’ jibe and in Spencer Vignes’ A Few Good Men said: “We sacked Mike Bailey because we weren’t playing attractive football, allegedly. Things were changing. Brighton had never been so high.

“We were doing well, but we weren’t seen as a flamboyant side. I was never happy with the press because they were creating this boring talk. Some of the stuff they used to write really annoyed me.”

Striker Andy Ritchie was also supportive of the management. He told journalist Nick Szczepanik: “Mike got everyone playing together. Everybody liked Mike and John Collins, who was brilliant. When a group of players like the management, it takes you a long way. When you are having things explained to you and training is good and it’s a bit of fun, you get a lot more out of it.”

Born on 27 February 1942 in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, he went to the same school in Gorleston, Norfolk, as the former Arsenal centre back Peter Simpson. His career began with non-league Gorleston before Charlton Athletic snapped him up in 1958 and he spent eight years at The Valley.

During his time there, he was capped twice by England as manager Alf Ramsey explored options for his 1966 World Cup squad. Just a week after making his fifth appearance for England under 23s, Bailey, aged 22, was called up to make his full debut in a friendly against the USA on 27 May 1964.

He had broken into the under 23s only three months earlier, making his debut in a 3-2 win over Scotland at St James’ Park, Newcastle, on 5 February 1964.He retained his place against France, Hungary, Israel and Turkey, games in which his teammates included Graham Cross, Mullery and Martin Chivers.

England ran out 10-0 winners in New York with Roger Hunt scoring four, Fred Pickering three, Terry Paine two, and Bobby Charlton the other.

Eight of that England side made it to the 1966 World Cup squad two years later but a broken leg put paid to Bailey’s chances of joining them.

“I was worried that may have been it,” Bailey recalled in his autobiography, The Valley Wanderer: The Mike Bailey Story (published in November 2015). “In the end, I was out for six months. My leg got stronger and I never had problems with it again, so it was a blessing in disguise in that respect.

“Charlton had these (steep) terraces. I’d go up to them every day, I was getting fitter and fitter.”

In fact, Ramsey did give him one more chance to impress. Six months after the win in New York, he was in the England team who beat Wales 2-1 at Wembley in the Home Championship. Frank Wignall, who would later spend a season with Bailey at Wolves, scored both England’s goals.

“But it was too late to get in the 1966 World Cup side,” said Bailey. “Alf Ramsey had got his team in place.”

During his time with the England under 23s, Bailey had become friends with Wolves’ Ernie Hunt (the striker who later played for Coventry City) and Hunt persuaded him to move to the Black Country club for a £40,000 fee.

Thus began an association which saw him play a total of 436 games for Wolves over 11 seasons.

In his first season, 1966-67, he captained the side to promotion from the second tier and he was also named as Midlands Footballer of the Year.

Wolves finished fourth in the top division in 1970-71 and European adventures followed, including winning the Texaco Cup of 1971 – the club’s first silverware in 11 years – and reaching the UEFA Cup final against Tottenham a year later, although injury meant Bailey was only involved from the 55th minute of the second leg and Spurs won 3-2 on aggregate.

Two years later, Bailey, by then 32, lifted the League Cup after Bill McGarry’s side beat Ron Saunders’ Manchester City 2-1 at Wembley with goals by Kenny Hibbitt and John Richards. It was Bailey’s pass to Alan Sunderland that began the winning move, Richards sweeping in Sunderland’s deflected cross.

This was a side with solid defenders like John McAlle, Frank Munro and Derek Parkin, combined with exciting players such as Irish maverick centre forward Derek Dougan and winger Dave Wagstaffe.

Richards had become Dougan’s regular partner up front after Peter Knowles quit football to turn to religion. Discussing Bailey with wolvesheroes.com, Richards said: “He really was a leader you responded to and wanted to play for. If you let your standards slip, he wasn’t slow to let you know. I have very fond memories of playing alongside him.”

In a lengthy tribute to Bailey in the Wolverhampton Express & Star to mark his 80th birthday, journalist Paul Berry interviewed several of his former teammates.

“He gave me – just as he did with all the young players coming into the team – so much help and guidance in training and matches on and off the pitch,” said Richards.

“There were so many little tips and pieces of advice and I remember how he first taught me how to come off defenders. He would say ‘when I get the ball John, just push the defender away, come towards me, lay the ball off and then go again’.

“There was so much advice that he would give to us all, and it had a massive influence.”

Midfielder Hibbitt, another Wolves legend who made 544 appearances for the club, said: “He was the greatest captain I ever played with.”

Steve Daley added: “Mike is my idol, he was an absolute inspiration to me when I was playing.”

Winger Terry Wharton added: “He was a great player…a bit of a Jekyll and Hyde character as well. On the pitch he was a great captain, a winner, he was tenacious and he was loud.

“He got people moving and he got people going and you just knew he was a captain. And then off the pitch? He could have been a vicar.”

When coach Sammy Chung stepped up to take over as manager, Bailey found himself on the outside looking in and chose to end his playing days in America, with the Minnesota Kicks, who were managed by the former Brighton boss Freddie Goodwin.

He returned to England and spent the 1978-79 season as player-manager of Fourth Division Hereford United and in March 1980 replaced Andy Nelson as boss at Charlton Athletic. He had just got the Addicks promoted from the Third Division when he replaced Mullery at Brighton.

In a curious symmetry, Bailey’s management career in England (courtesy of managerstats.co.uk) saw him manage each of those three clubs for just 65 games. At Hereford, his record was W 32, D 11, L 22; at Charlton W 21, D 17, L 27; at Brighton, W 20 D 17, L 28.

In 1984, he moved to Greece to manage OFI Crete, he briefly took charge of non-league Leatherhead and he later worked as reserve team coach at Portsmouth. Later still, he did some scouting work for Wolves (during the Dave Jones era) and he was inducted into the Wolves Hall of Fame in 2010.

In November 2020, Bailey’s family made public the news that he had been diagnosed with dementia hoping that it would help to highlight the ongoing issues around the number of ex-footballers suffering from it.

Perhaps the last words should go to Bailey himself, harking back to that 1981 article when his words were so prescient bearing in mind what would follow his time in charge.

“We don’t have a training ground. We train in a local park. The club have tried to remedy this and I’m sure they will. But such things hold you back in terms of generating the feeling of the big time,” he said.

“I must compliment the people who are responsible for getting the club where it is. They built a team, won promotion twice and the fans flocked in. Now is the time to concentrate on developing the Goldstone Ground. When we build our ground, we will have the supporters eager to fill it.”

Pictures from various sources: Goal and Shoot! magazines; the Evening Argus, the News of the World, and the Albion matchday programme.

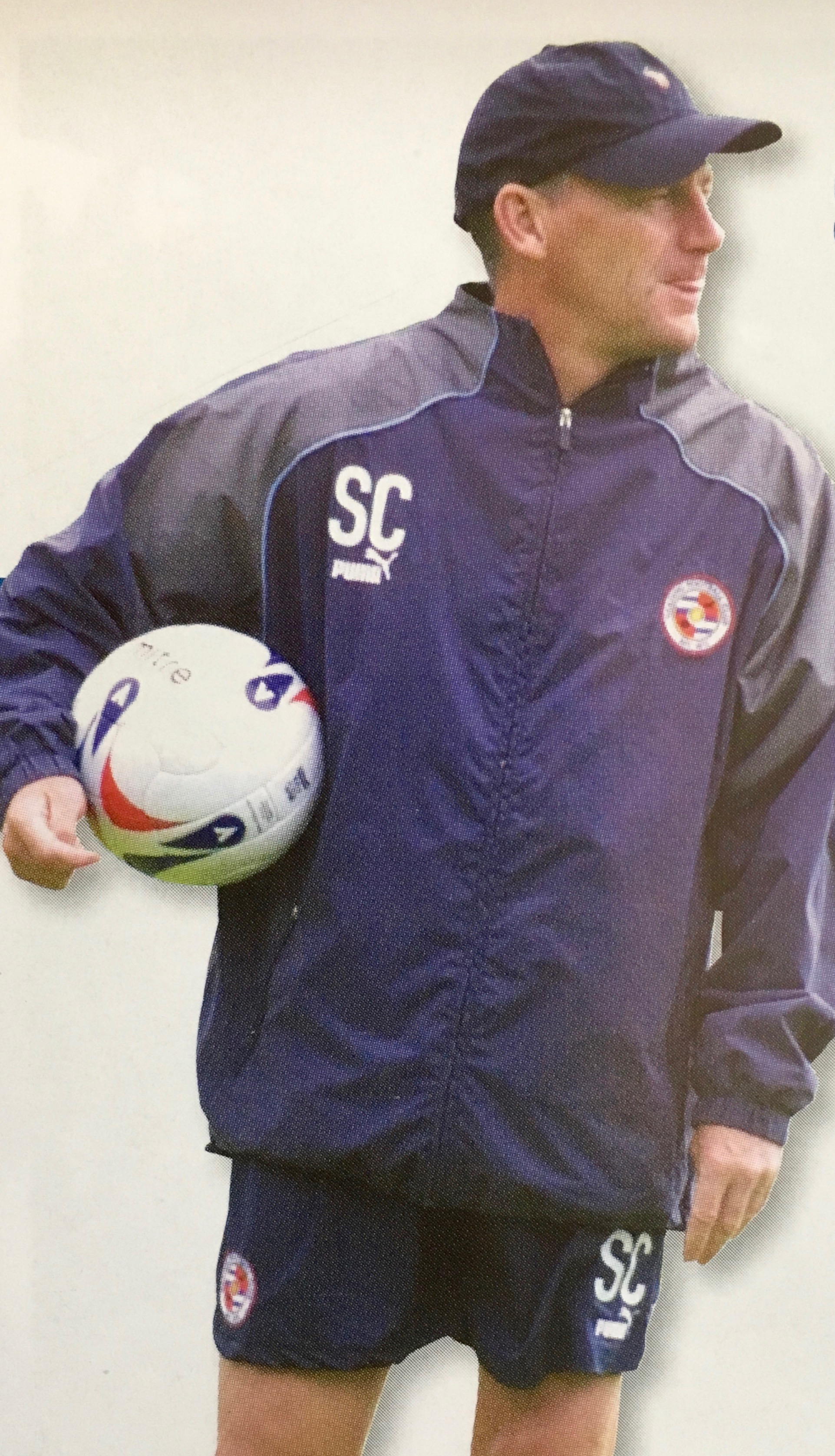

STEVE Coppell was not the first former Manchester United player I saw become manager of Brighton. More than 30 years previously Busby Babe

STEVE Coppell was not the first former Manchester United player I saw become manager of Brighton. More than 30 years previously Busby Babe