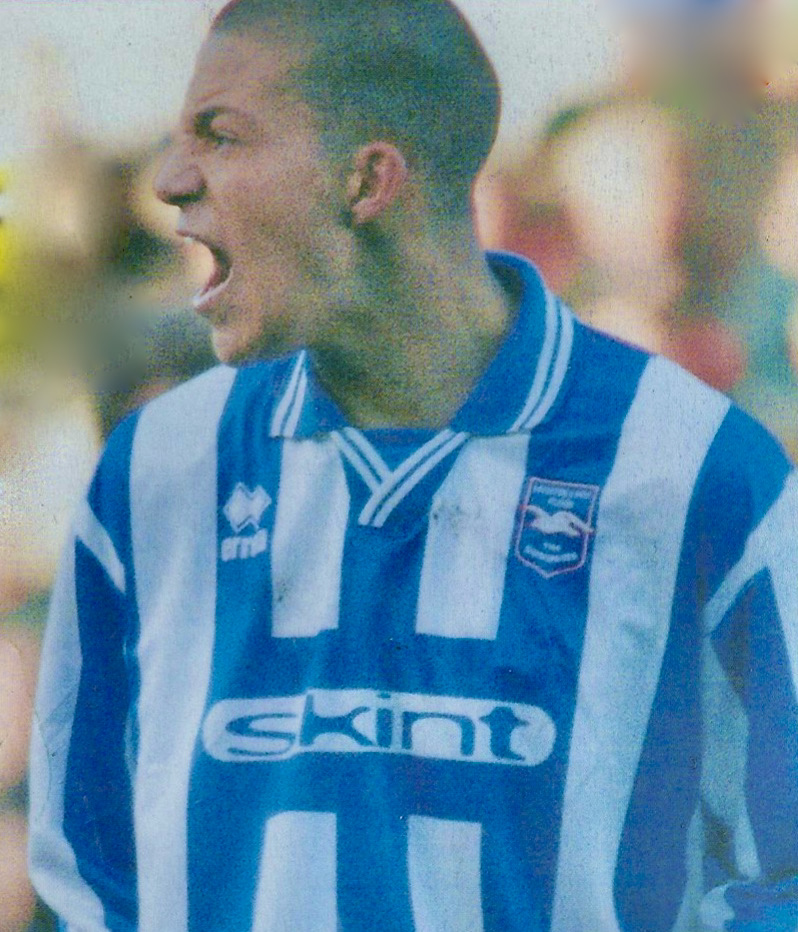

EVERY NOW AND AGAIN as a football supporter a truly special player stands out well above the rest you’ve watched. Bobby Zamora was most definitely in that category.

As the new year dawns on what will be my 55th year supporting Brighton & Hove Albion, it is perhaps fitting to spend a little time remembering just how good Zamora was for the Seagulls before his outstanding ability to score goals was taken to higher levels: Tottenham Hotspur, West Ham, Fulham and ultimately, and, quite deservedly, England.

That he came back to the Albion from QPR as his career began to ebb was nothing short of a bonus – and, while I’m not a big gambler, I was delighted to get a modest return from the bookies when my punt on him being the last goalscorer came good after he had gone on as a sub at Elland Road on 15 October 2015 and chipped the winner (below) to register his first goal since rejoining!

“That goal was definitely the highlight of my season,” Zamora told interviewer Adam Virgo in a Seagulls World interview. “It was my first goal since coming back and to score the winner so late in the game was unbelievable. It was a special moment for me, and it settled the nerves knowing that we’d got the three points.”

Just four days later, Zamora repeated the feat going on as a 76th-minute substitute for Tomer Hemed at home to Bristol City and beating goalkeeper Frank Fielding with a low shot from 15 yards out. Albion won 2-1; Sam Baldock having levelled things up against his former club after Derrick Williams opened the scoring for City.

Unfortunately, Zamora managed just five more in that second spell. He made 10 starts plus 16 as a sub in Chris Hughton’s side but he was struggling with a hip injury.

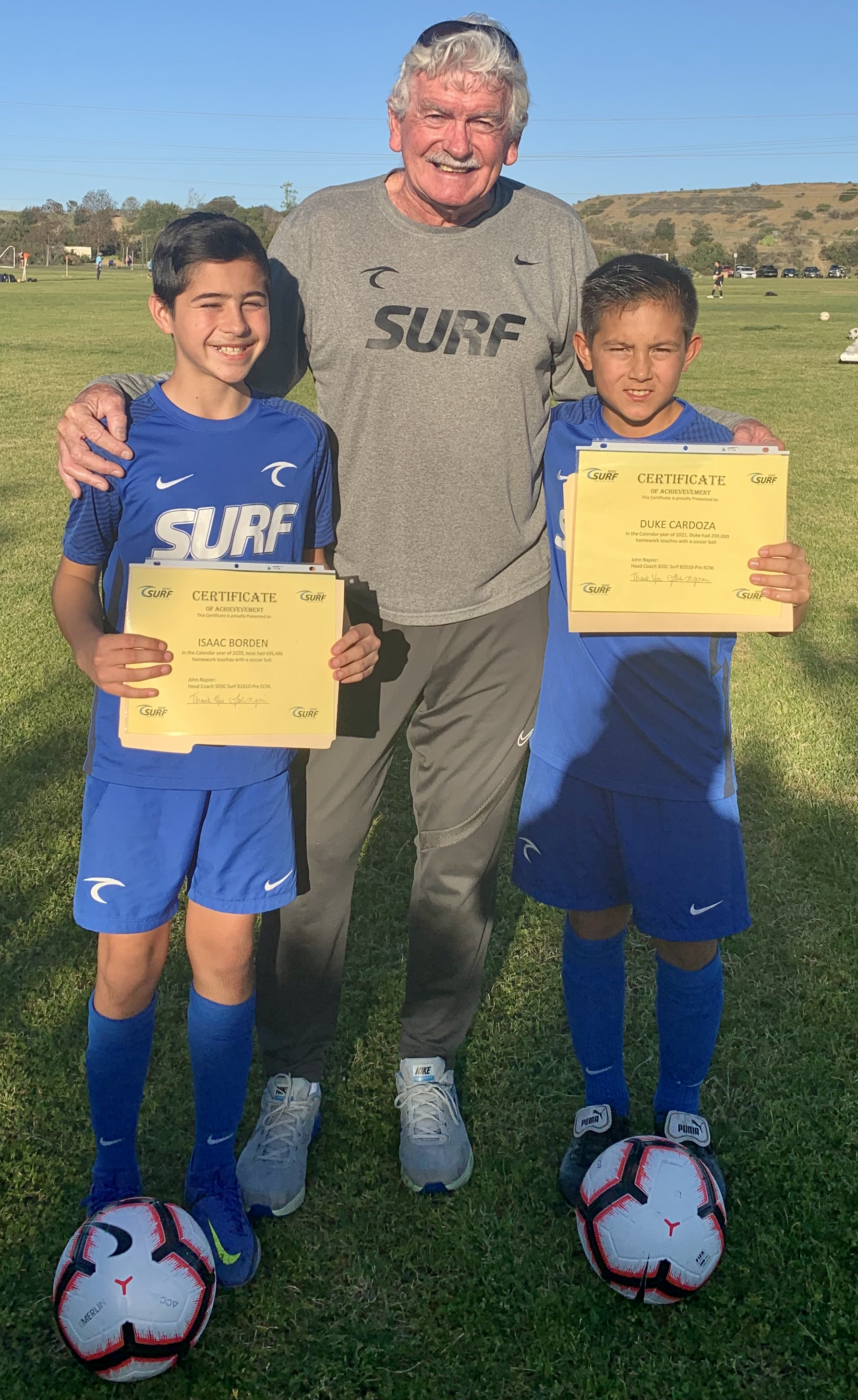

It eventually caught up with him and prevented him from contributing further to Albion’s aim of promotion back to the elite; his last game being as a sub in a 0-0 draw at home to Sheffield Wednesday on 8 March 2016. “If I was fit, I would have scored some goals and we’d have been promoted automatically,” he told the UndrThe Cosh podcast (pictured above).

Thankfully another returning striker in the shape of Glenn Murray completed that task the following season and went on to cement his own place in Albion’s history: his 111 goals in 287 appearances putting him second in the list of Brighton’s all-time top goalscorers.

Each of the different eras I’ve watched the Albion has thrown up truly memorable players who have generated their own air of excitement and anticipation because of the goals they scored.

The first one for me was Alex Dawson, who netted seven in the first five games I watched in 1969. Then along came Willie Irvine whose goalscoring in third tier Albion’s promotion-winning season of 1972 earned him an unexpected recall to the Northern Ireland side – and an appearance (that I went to watch) in a 1-0 win against England at Wembley.

Next, of course, was the truly outstanding Peter Ward, who jinked his way past defenders with apparent ease and scored goals for fun, his 36 goals in 1976-77 smashing a decades-old record. Like Zamora, he came back to the scene of past glories (albeit only on loan) and scored a magnificent winner against the team he supported as a boy, Manchester United.

Garry Nelson, with 32 goals, and Kevin Bremner were a superb front pair in another third tier promotion-winning line-up in 1988 while, in 1990-91, Mike Small and John Byrne combined brilliantly to take the Seagulls within a hair’s breadth of a return to the big time.

The arrival of a beanpole of a kid with an eye for goal in Zamora completely transformed Albion’s fortunes under Micky Adams and he was the talisman in back-to-back promotions following years in the doldrums.

Zamora’s Albion story is pretty well known but let’s remind ourselves of how it all began.

Depending on whose account you believe more, it was either Dick Knight or Adams who had the foresight to bring Zamora to the Withdean.

Adams said: “The first time I saw him he came onto the training ground; he looked like a kid. But he was tall and gangly with a useful left foot; there was potential there.”

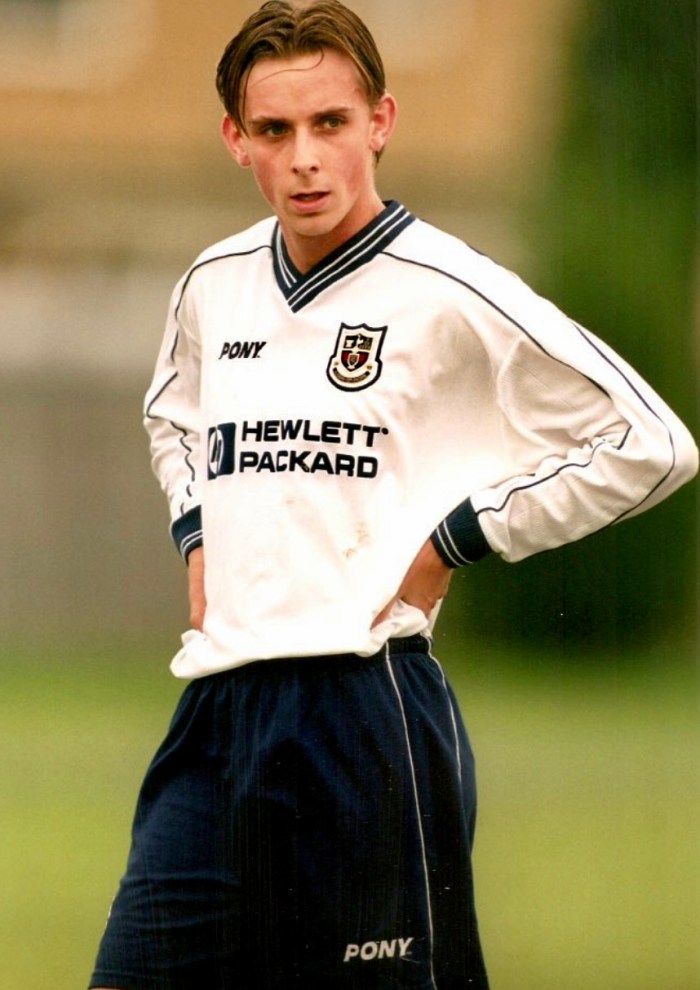

In fact, Zamora might never have arrived in Sussex if Albion had been successful in securing a permanent deal for on-loan Lorenzo Pinamonte. When Brentford outbid Brighton for the services of the Bristol City loanee, Albion turned their attention to Zamora (left), a Bristol Rovers player who was only getting sub appearances under Ian Holloway but had scored eight goals in six games on loan at nearby non-league Bath City.

“He was six foot one and we knew he had a very good first touch and could hold the ball up well, the type of player we wanted,” Knight recounted in his autobiography Mad Man: From The Gutter to the Stars (Vision Sports Publishing, 2013).

Zamora duly arrived on loan and scored six in six matches (including a hat-trick in a 7-1 away win at Chester). He scored an equaliser and was named Man of the Match on his debut v Plymouth and by the end of February was Player of the Month.

While Knight and Adams wanted him to stay, he insisted on returning to Rovers where he thought he might force his way into Holloway’s starting line-up. But it was back only to the bench as Nathan Ellington, Jason Roberts and Jamie Cureton were ahead of him in the pecking order.

As preparations began for the new season, Albion offered £60,000 for Zamora but Rovers chairman Geoff Dunford wanted £250,000. An incredulous Knight said he wouldn’t go higher than £100,000 and couldn’t believe they could demand such a figure for someone who hadn’t actually started a first team game.

Zamora had Rovers’ youth team coach Phil Bater to thank for forcing through the move. He accompanied the shy youngster into a meeting with Holloway, who tried to say he’d get some games if he stayed. Bater reckoned the youngster was being strung along and argued Zamora’s cause saying he stood more chance of playing if Rovers let him join the Albion.

After some brinkmanship from each club’s respective chairmen, with Knight threatening to walk away from the deal, it finally went through two days before the start of the season, although Albion’s chairman reluctantly agreed to a 30 per cent sell-on clause for the player.

Zamora instantly became one of the top earners on £2,000 a week with a goal bonus built in.

“It was an absolute coup that we had finally secured this player,” said Knight. “I could only see good things in him, could only see that he would be a huge asset to us.

“Football is all a matter of opinions. There is little science to it. For me, Zamora was the best signing I ever made.”

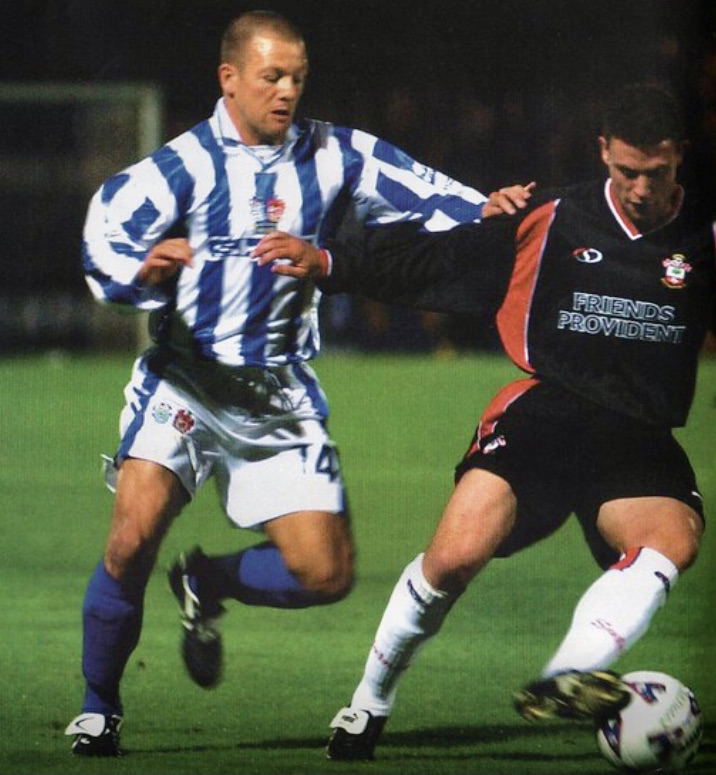

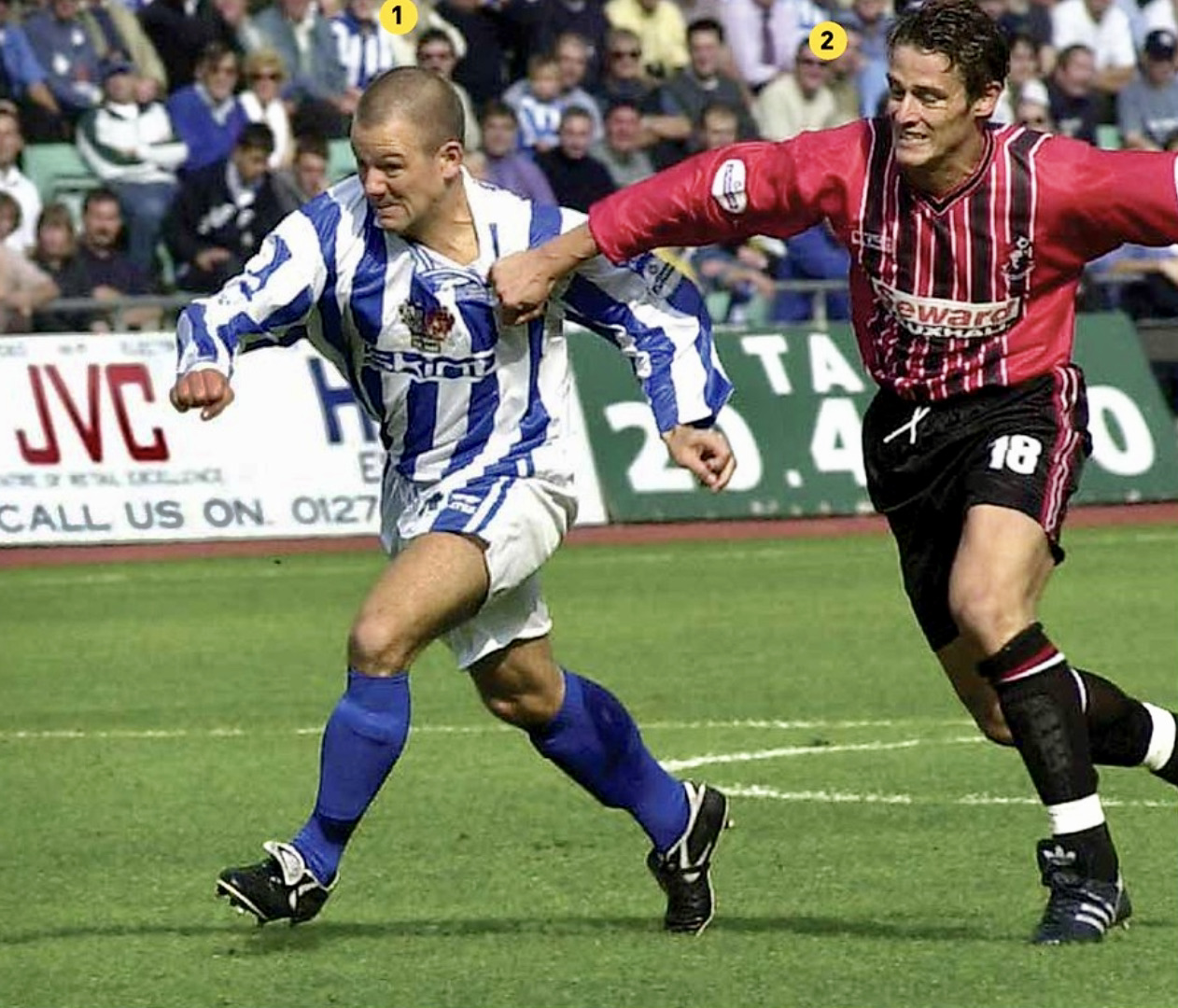

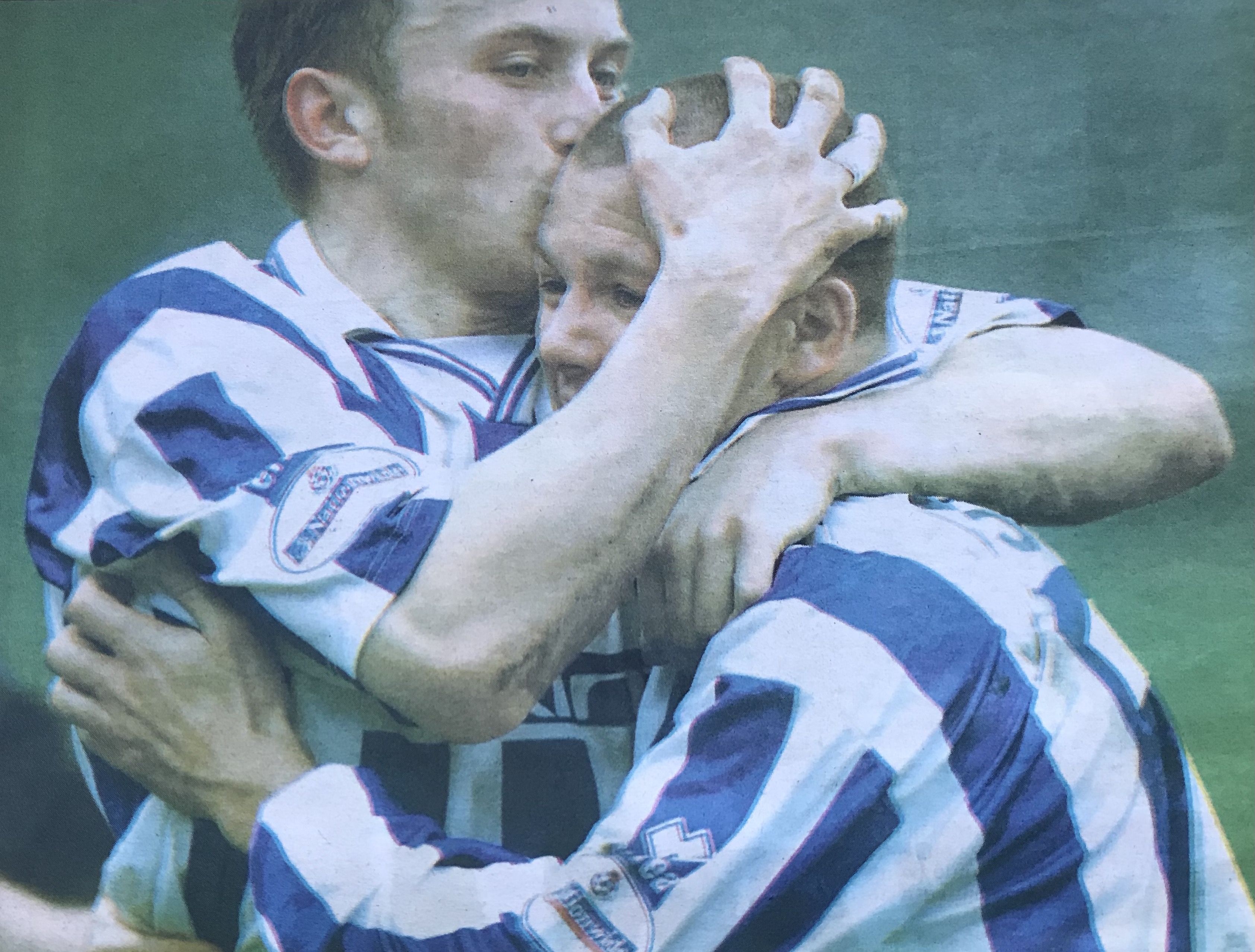

Not only did Zamora manage to score 31 goals as Albion won promotion from the basement division, he went one better when they went straight to the top of the third tier the following season, netting 32 times in 46 matches.

A significant number of those goals came courtesy of Zamora’s excellent understanding with left-footed right-back Paul Watson, of whom he said: “He created a lot of goals for me with those quick free kicks. He didn’t put a foot wrong too often and was very underrated. He never got the credit his hard work deserved.”

Expanding on it in another interview, he said: “Whenever Watto got the ball I knew precisely where I needed to run to and he knew where to deliver it. It was such a great connection: Watto has an absolutely wonderful left foot and it made my job as a striker so much easier when you get deliveries like that.”

Declaring that even in the Premiership he hadn’t come across anybody with a better left foot, he added: “I was very lucky to have played in the same team as him; he created numerous goals for me; not only with his deliveries but with his intelligent play as well.”

Watson had arrived at the club with Charlie Oatway and was part of a cluster of players who had served under Adams at Brentford and Fulham. When Adams and assistant Bob Booker steered Albion to promotion as fourth tier champions, Zamora was player of the season and he and Danny Cullip were named in the PFA divisional XI.

Not long into the following season, the lure of taking over as manager at a Premier League club saw Adams quit Brighton, initially to become Dave Bassett’s no.2 at Leicester City, but with the promise of succeeding him.

“While I thought I had a shot at another promotion, it wasn’t a certainty,” Adams explained. “I knew I had put together a team of winners, and I knew I had a goalscorer in Bobby Zamora, but football’s fickle finger of fate could have disrupted that at any time.”

His successor, Peter Taylor, knew how fortunate he was to inherit an experienced squad, and said: “Of course the greatest asset we had was Bobby Zamora. Having him meant that we could play a front two at home and away from home we could play him on his own and he would still get us a goal out of nothing. He was an incredible player and miles too good for that level.”

And Zamora wasn’t only a star on the pitch, as Knight spoke about in his autobiography. “When he was at his zenith at Brighton, the requests we got for him to visit schools, hospitals and go to prize-givings far outweighed all the other players together, but he was always amenable. He was never starry, never refused. I couldn’t speak more highly of Bobby Zamora as a person.”

Knight recounted in his book how, after a 1-0 win at Peterborough, when Zamora missed a penalty but also scored the only goal of the game, Albion’s promotion to the second tier was confirmed and in his own inimitable way Posh boss Barry Fry said to Brighton’s star striker: “You’re a fucking great player and you’ll play for England one day, I’m fucking sure of it.”

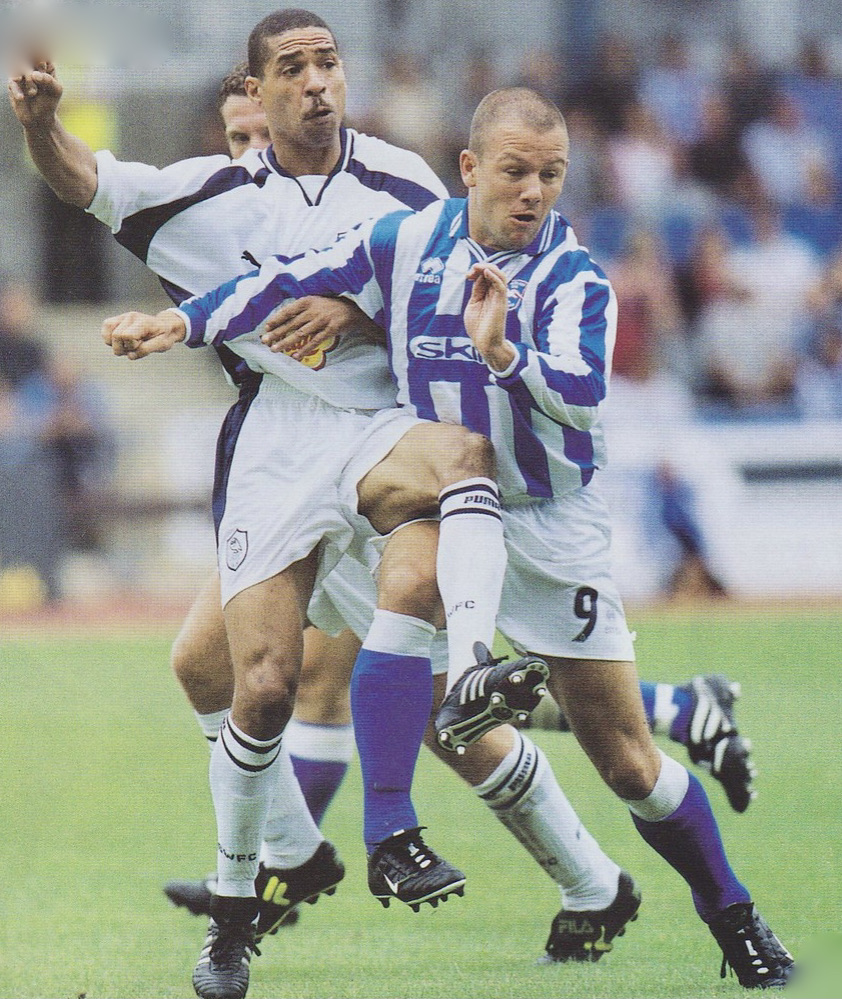

Zamora was still only 21 when Tottenham signed him from relegated Brighton in July 2003. He left the south coast having scored a total of 83 goals in 136 appearances but in his last season in the stripes he netted just 14 as the Seagulls battled unsuccessfully to retain their tier two status.

Unfortunately, he missed eleven matches with a dislocated shoulder and, had former Premier League striker Paul Kitson been fit to play alongside him (he managed only seven starts plus three off the bench), the season may well have had a different outcome.

Everton’s Bill Kenwright had offered £3m for Zamora during the season but their manager Walter Smith seemed less convinced and, with Kevin Campbell and Wayne Rooney likely to be ahead of him, Zamora stayed in Sussex.

But chairman Dick Knight promised not to stand in his way if an opportunity was presented at the end of the season and that came from Tottenham. Manager Glenn Hoddle and assistant Chris Hughton had been to see Zamora in action at the Withdean on a number of occasions.

Spurs chairman Daniel Levy played hardball over the deal. Eventually, Knight settled on a £1.5m fee but, because of the original sell-on clause, £450,000 was due to Bristol Rovers.

Hoddle told The Guardian: “He has got good pace and great movement on and off the ball. No disrespect to Brighton, they have got a good team down there, but we have got players here who can make the most of his movement.”

The player’s agent Phil Smith told the newspaper: “The fee for Bobby is £1.5m which is a decent price in today’s market for a Second Division striker.

“It has been a long time coming for Bobby but he is delighted to be going into the Premiership. It has always been an ambition.”

Disappointed Albion manager Steve Coppell observed: “It is a big move for Bobby and nobody really expected we could hang onto him for much longer. But it has blown a big hole in any plans I had. I don’t have a better option than playing with Bobby Zamora up front.”

When he arrived at Spurs, one of the senior pros who took him under his wing was none other than Gus Poyet.

“As a young guy coming into the team, he was one of the senior pros who would always talk to me and encourage me,” Zamora told the matchday programme. “He didn’t have to do that, but he went out of his way to do so and you could see he had coaching qualities. He would often point things out on the pitch that you’d pick up on, and when he spoke, you’d listen.

“He wasn’t starting every game either, so in training I did more things with him than maybe the rest. I really got on well with him.”

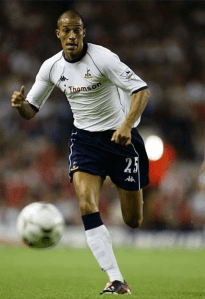

As it turned out, Zamora made only 18 appearances for Spurs (11 as a substitute) and only scored once – ironically a single goal that knocked West Ham out of the Carling Cup in October 2003.

In January 2004, Spurs chose to use him as a makeweight in taking Jermain Defoe from the Boleyn Ground to White Hart Lane.

Phlegmatic Zamora didn’t look on it as a failure but embraced the “learning curve” of training alongside the likes of Poyet, Robbie Keane, Darren Anderton and Jamie Redknapp.

“I came away a better player and with more experience,” he said. “Glenn Hoddle had signed me and then he got sacked not long afterwards. David Pleat took charge and we didn’t really see eye-to-eye, but the lads and the club were brilliant and I learned so much from my time there.

“I took a chance by stepping back down to the Championship with West Ham – but it was the opportunity of playing regular football again that was the pull for me.”