DEAN WILKINS might have lived in the shadow of his more famous elder England international brother Ray but he certainly carved out his own footballing history, much of it with Brighton.

Albion fans of a certain vintage will never forget the sumptuous left-footed free-kick bouffant-haired captain Wilkins scored past Phil Parkes at the Goldstone Ground which edged the Seagulls into the second-tier play-offs in 1991.

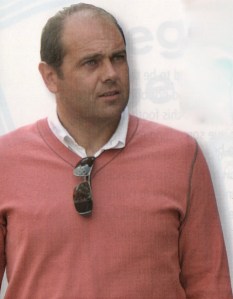

Supporters from the mid-noughties era would only recall the balding boss of a mid-table League One outfit at Withdean comprising mainly home-grown players who Wilkins had brought through from his days coaching the youth team.

After Dick Knight somewhat unceremoniously brought back Micky Adams over Wilkins’ head in 2008, he quit the club rather than stay on playing second fiddle and subsequently went west to Southampton where he worked under Alan Pardew and his successor Nigel Adkins as well as taking caretaker charge of the Saints in between the two reigns.

Wilkins’ initial association with the Seagulls went back to 1983, when Jimmy Melia brought him to the south coast from Queens Park Rangers shortly after Albion’s FA Cup final appearances at Wembley.

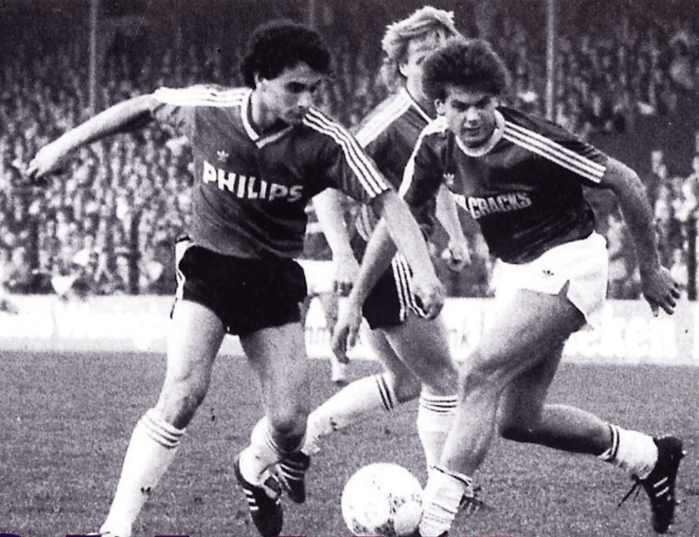

Melia’s successor Chris Cattlin only gave him two starts back then and although he pondered a move to Leyton Orient, where he’d had 10 matches on loan, he opted to accept to try his luck in Holland when his Dutch Albion teammate Hans Kraay set him up with a move to PEC Zwolle. Playing against the likes of Johann Cruyff, Marco Van Basten and Ruud Gullit proved to be quite the footballing education for Wilkins.

After two years in the Netherlands, 25-year-old Wilkins rejoined the relegated Seagulls in the summer of 1987 as the club prepared for life back in the old Third Division under Barry Lloyd.

Relegation had led to the sale for more than £400,000 of star assets Danny Wilson, Terry Connor and Eric Young but more modest funds were allocated to manager Lloyd for replacements: £10,000 for Wilkins, £50,000 for Doug Rougvie, who signed from Chelsea and was appointed captain, Garry Nelson, a £72,500 buy from Plymouth and Kevin Bremner, who cost £65,000 from Reading. Midfield enforcer Mike Trusson was a free transfer.

The refreshed squad ended up earning a swift return to the second tier courtesy of a memorable last day 2-1 win over Bristol Rovers at the Goldstone.

At the higher level, Wilkins had the third highest appearances (40 + two as sub) as Albion finished just below halfway in the table. The following season Wilkins was appointed captain and was ever-present as Albion made it to the divisional play-off final against Notts County at Wembley, having made it to the semi-final v Millwall courtesy of the aforementioned spectacular free kick v Ipswich.

Wilkins scored again at Wembley but it turned out only to be a consolation as the Seagulls succumbed 3-1 to Neil Warnock’s side.

As the 1992-93 season got underway, Wilkins, having just turned 30, was the first matchday programme profile candidate for the opening home game against Bolton Wanderers (a 2-1 win) when he revealed the play-off final defeat had been “the biggest disappointment of my career”.

The 1993-94 season was a write-off from October onwards when he damaged the medial ligaments in both his knees after catching both sets of studs in the soft ground at home against Exeter City.

Although injury plagued much of the time during Liam Brady’s reign as manager, the Irishman acknowledged his ability saying: “He is a very fine footballer and a tremendous passer of the ball and he possesses a great shot.”

Ahead of the start of the 1995-96 season, Wilkins was granted a testimonial game against his former club QPR, managed at the time by big brother Ray. But at the end of the season, when the Seagulls were relegated to the basement division, he was one of six players given a free transfer.

Born in Hillingdon on 12 July 1962, Wilkins couldn’t have wished for a more football-oriented family. Dad George had played for Brentford, Leeds, Nottingham Forest and Hearts and appeared at Wembley in the first wartime FA Cup final. While Ray was the brother who stole the limelight, Graham and Steve also started out at Chelsea.

In spite of those older brothers who also made it as professionals, Wilkins attributed his development at QPR, who he joined straight from school as an apprentice in 1978, to youth coach John Collins (who older fans will remember was Brighton’s first team coach under Mike Bailey).

He made seven first team appearances for Rangers, his debut being as a substitute for Glenn Roeder in a 0-0 draw with Grimsby Town on 1 November 1980. After joining the Albion in August 1983, he had to wait until 10 December that year to make his debut, in a 0-0 draw at Middlesbrough, in place of the absent Tony Grealish. He started at home to Newcastle a week later (a 1-0 defeat), this time taking the midfield spot of injured Jimmy Case.

Perhaps the writing was on the wall when Cattlin secured the services of Wilson from Nottingham Forest, initially on loan, and although Wilkins had a third first team outing in a 2-0 FA Cup third round win at home to Swansea City, boss Cattlin didn’t pick him again. Instead, he joined Orient on loan in March 1984.

A long career in coaching began when Wilkins was brought back to the Albion in 1998 by another ex-skipper, Brian Horton, who had taken over as manager. With Martin Hinshelwood as director of a new youth set-up, Wilkins was appointed the youth coach – a position he held for the following eight years.

His charges won 4-1 against Cambridge United in his first match, with goals from Duncan McArthur, Danny Marney and Scott Ramsay (two).

That backroom role continued as managers came and went over the following years during which a growing number of youth team products made it through to the first team: people like Dan Harding and Adam Virgo and later Adam Hinshelwood, Joel Lynch, Dean Hammond and Adam El-Abd.

At the start of the 2006-07 season, with Albion back in the third tier after punching above their weight in the Championship for two seasons, Wilkins was rewarded for his achievements with the youth team with promotion to first team coach under Mark McGhee.

By then, more of the youngsters he’d helped to develop were in or getting close to the first team, for example Dean Cox, Jake Robinson, Joe Gatting and Chris McPhee.

After an indifferent start to the season – three wins, three defeats and a draw – Knight decided to axe McGhee and loyal lieutenant Bob Booker and to hand the reins to Wilkins with Dean White as his deputy. Wilkins later brought in his old teammate Ian Chapman as first team coach.

Tommy Elphick, Tommy Fraser and Sam Rents were other former youth team players who stepped up to the first team. But, over time, it became apparent Knight and Wilkins were not on the same page: the young manager didn’t agree with the chairman that more experienced players were needed rather than relying too much on the youth graduates.

Indeed, in his autobiography Mad Man: From the Gutter to the Stars (Vision Sports Publishing, 2013), Knight said Wilkins hadn’t bothered to travel with him to watch Glenn Murray or Steve Thomson, who were added to the squad, and he was taking the side of certain players in contract negotiations with the chairman.

“In my opinion, his man-management skills were lacking, which was why I made the decision to remove him from the manager’s job,” he said. It didn’t help Wilkins’ cause when midfielder Paul Reid went public to criticise his man-management too.

Knight felt although Wilkins hadn’t sufficiently nailed the no.1 job, he could still be effective as a coach, working under Micky Adams. The pair had previously got on well, with Adams saying in his autobiography, My Life in Football (Biteback Publishing, 2017) how Wilkins had been “one of my best mates”.

But Adams said: “He thought I had stitched him up. I told him that I wanted him to stay. We talked it through and, at the end of the meeting, we seemed to have agreed on the way forward.

“I thought I’d reassured him enough for him to believe he should stay on. But he declined the invitation. He obviously wasn’t happy and attacked me verbally.

“I did have to remind him about the hypocrisy of a member of the Wilkins family having a dig at me, particularly when his older brother had taken my first job at Fulham.

“We don’t speak now which is a regret because he was a good mate and one of the few people I felt I could talk to and confide in.”

Knight knew his decision to sack the manager would not be popular with fans who only remembered the good times, but he pointed out they weren’t aware of the poor relationship he had with some first team players.

Knight described in his book how a torrent of “colourful language” poured out from Wilkins when he was called in and informed of the decision in a meeting with the chairman and director Martin Perry.

“He didn’t take it at all well, although I suppose he felt he was fully justified,” wrote Knight. “He was fuming after what was obviously a big blow to his pride.”

Reporter Andy Naylor perhaps summed up the situation best in The Argus. “The sadness of Wilkins’ departure was that Albion lost not a manager, but a gifted coach,” he said. “Wilkins was not cut out for management.”

One year on, shortly after Alan Pardew took over as manager at League One Southampton, he appointed Wilkins as his assistant. They were joined by Wally Downes (Steve Coppell’s former assistant at Reading) as first team coach and Stuart Murdoch as goalkeeping coach.

Saints were rebuilding having been relegated from the Championship the previous season and began the campaign with a 10-point penalty, having gone into administration. The club had been on the brink of going out of business until Swiss businessman Markus Liebherr took them over.

A seventh place finish (seven points off the play-offs because of the deduction) meant another season in League One and the following campaign had only just got under way when Pardew, Downes and Murdoch were sacked. Wilkins was put in caretaker charge for two matches and then retained when Nigel Adkins, assisted by ex-Seagull Andy Crosby, was appointed manager.

It was the beginning of an association that also saw the trio work together at Reading (2013-14) and Sheffield United (2015-16).

Adkins, Crosby and Wilkins were in tandem as the Saints gained back-to-back promotions, going from League One runners up to Gus Poyet’s Brighton in 2011, straight through the Championship to the Premier League. But they only had half a season at the elite level before the axe fell and Mauricio Pochettino took over.

When the trio were reunited at Reading, Wilkins, by then 50, gave an exclusive interview to the local Reading Chronicle, in which he said: “This pre-season has given me time to learn about the characters of the players we’ve got at Reading and find out what makes them tick.

“It’s my job then to make sure every player maximises his potential. That’s what I see my role as, to bring out the very best of them from now on and make them strive to attain new levels of performance.

“I will always keep working toward that goal. If we can do that with every individual and get maximum performances out of them, I believe we will be in for a great season.

“We’re back together now and it’s going fantastically well. I have loved every minute of it. I’m used to working with Nigel and Andy and we are carrying out similar work to what we’ve done in the past.”

The Royals finished seventh, a point behind Brighton, who qualified for the play-offs, and the trio were dismissed five months into the following season immediately following a 6-1 thrashing away to Birmingham City.

Six months later the trio were back in work, this time at League One Sheffield United, but come the end of the 2015-16 season, after the Blades had finished in their lowest league position since 1983, they were shown the door.

Between January 2018 and July 2019, Wilkins worked for the Premier League assessing and reporting on the accuracy, consistency, management and decision-making of match officials.

In the summer 0f 2019, he was appointed Head of Coaching at Crystal Palace’s academy, a job he held for 15 months.

A return to involvement with first team football was presented by his former Albion player Alex Revell, who’d been appointed manager of League Two Stevenage Borough. Glad to support and mentor Revell in his first managerial post, Wilkins spent a year as assistant manager at the Lamex Stadium.