IN ALBION’S bleak midwinter of 1972-73, manager Pat Saward was desperate to try to reverse a worrying run of defeats.

The handful of additions he’d made to the squad promoted from the old Third Division in May 1972 had not made the sort of improvements in quality he had hoped for.

An injury to Norman Gall’s central defensive partner Ian Goodwin didn’t help matters and Saward chopped and changed the line-up from week to week to try to find the right formula.

Previously frozen out former captain John Napier was restored for a handful of games (before being sold to Bradford City for £10,000). The loan ranger’ (as Saward was dubbed for the number of temporary signings he brought in) then tried Luton Town’s John Moore in Goodwin’s absence.

Youngster Steve Piper was given his debut at home to high-flying Burnley, but Albion lost that 1-0. Then Saward tried left-back George Ley in the middle away to Preston, but that didn’t work either. North End ran out comfortable 4-0 winners with Albion’s rookie ‘keeper Alan Dovey between the sticks after regular no.1 Brian Powney went down with ‘flu.

As December loomed, and with Goodwin still a couple of weeks away from full fitness after a cartilage operation, Saward turned to John McGrath, a no-nonsense, rugged centre-half who had played close on 200 games for Southampton over five years.

“With his rolled-up sleeves, shorts hitched high to emphasise implausibly bulging thigh-muscles, an old-fashioned haircut and a body dripping with baby oil, ‘Big Jake’ cut an imposing figure,” to quote the immensely readable saintsplayers.co.uk.

In Ivan Ponting’s obituary in the Independent following McGrath’s death at 60 on Christmas Day 1998, he reckoned his “lurid public persona was something between Desperate Dan and Attila the Hun”.

Although McGrath had begun the 1972-73 season in the Saints side, the emerging Paul Bennett had taken his place, so a temporary switch to the Albion offered a return to first team football.

Albion had conceded eight goals in three straight defeats and hadn’t registered a goal of their own, so, even though the imposing centre-half was approaching the end of a playing career that had begun with Bury in 1955, it was hoped his know-how defending against some of the best strikers in the country might add steel in the heart of the defence, and stem the flow of goals.

In short, it didn’t work. McGrath played in three matches and all three ended in defeats, with another eight goals conceded.

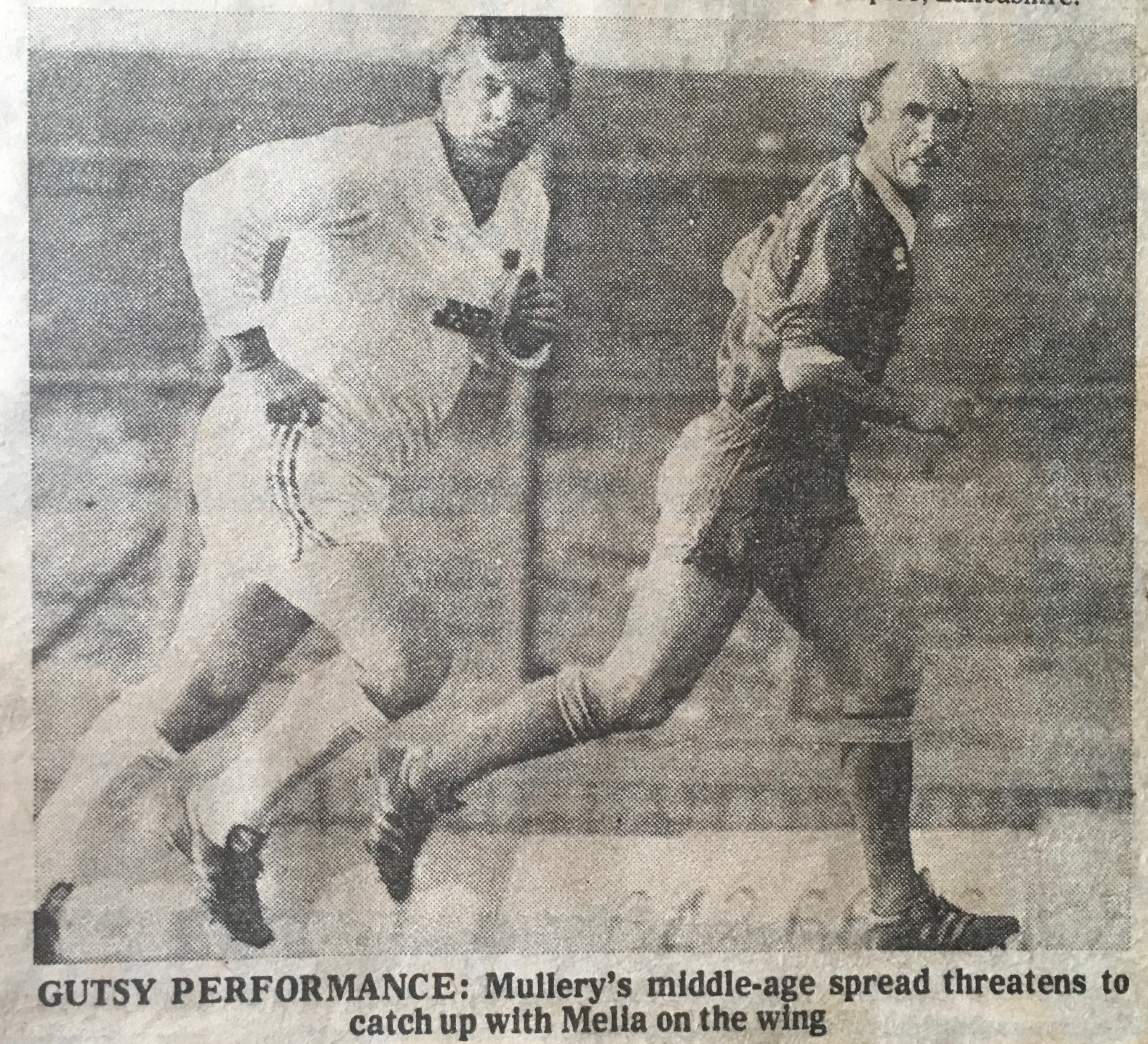

In his first match (above left), Middlesbrough won 2-0 at the Goldstone. At least the deficit was slimmer in his second game: a 1-0 loss away to George Petchey’s Orient in which Lewes-born midfielder Stan Brown played the last of nine games on loan from Fulham.

McGrath’s third match saw Albion succumb to a thrashing at Carlisle United. By then, Brighton had lost five in a row and still hadn’t managed to score a single goal. Stalwart Norman Gall was dropped to substitute to allow the returning Goodwin to line up alongside McGrath, and Bert Murray led the side out resplendent in the second strip of red and black striped shirts and black shorts.

Carlisle hadn’t read the script, though, and promptly went 5-0 up. To compound Albion’s agony, with 20 minutes still to play, goalkeeper Powney was carried off concussed and with a broken nose.

In those days before substitute goalkeepers, Murray (who’d swapped to right-back that day with Graham Howell moving into his midfield berth) took over the gloves. Miraculously, Albion won a penalty and because usual spot kick taker Murray was between the sticks, utility man Eddie Spearritt took responsibility having relinquished the job after a crucial miss in a game in 1970.

Thankfully, he buried it, finally to make a much-awaited addition to that season’s ‘goals for’ column.

No more was seen of McGrath, however. Gall was restored to the no.5 shirt and was variously partnered by Goodwin, Piper and, towards the end of the season, Spearritt.

After another heavy defeat, 4-0 at Sunderland, which had seen another rare appearance by Dovey in goal, he was transfer-listed along with Gall and Bertie Lutton, as Saward pointed the finger. Lutton got a surprise move to West Ham but Gall stayed put and Dovey was released at the end of the season without playing another game.

The run of defeats eventually extended to a total of 13 and was only alleviated after a big shake-up for the home game versus Luton Town on 10 February.

Powney, who’d conceded five at Fulham in the previous game, was replaced by Aston Villa goalkeeper Tommy Hughes on loan; out went experienced striker Barry Bridges in favour of rookie Pat Hilton and exciting teenage winger Tony Towner made his debut. Albion won 2-0 with both goals from Ken Beamish, and the monkey was finally off their backs.

Although the following two games (away to Bristol City and Hull) were lost, results did pick up, but it was all too little too late and Albion exited the division only 12 months after their promotion.

Born in Manchester on 23 August 1938, McGrath sought unsuccessfully to get into the game as an amateur with Bolton Wanderers but at 17 he joined Bury who were in the old Division Two at the time.

Although they were subsequently relegated, McGrath was part of the 1961 side that went on to win the Third Division Championship. By the time they lifted the trophy, though, he had moved on to Newcastle United for a fee of £24,000, with Bob Stokoe (later renowned for steering Second Division Sunderland to a famous FA Cup win over Leeds United in 1973) a makeweight in the transfer.

It was a busy time for the young defender. On 15 March 1961, he made his one and only England Under-23 appearance against West Germany at White Hart Lane, Tottenham, playing alongside future World Cup winners George Cohen at right-back and the imperious Bobby Moore.

Also in the young England side for that 4-1 win was Terry Paine, who would later become a teammate at Southampton.

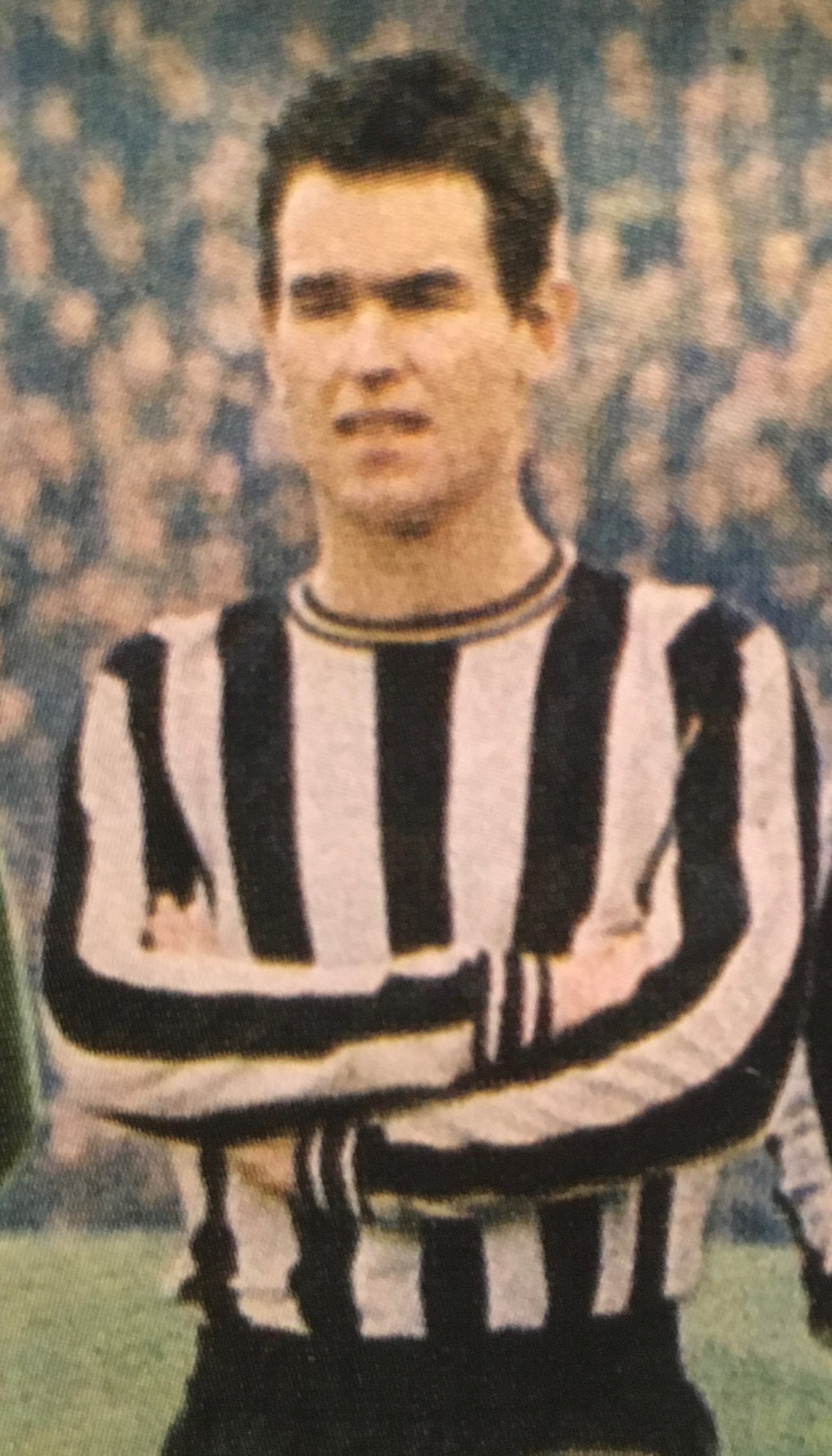

Newcastle had hoped the defender would prevent their relegation from the top flight, but it didn’t happen as they went down having conceded 109 goals; their worst ever goals against tally.

Joe Harvey eventually succeeded Charlie Mitten as manager as Newcastle adapted to life back in the Second Division, and McGrath (below left and, in team picture, back row, far left) played 16 matches in a side in which full-back George Dalton (below, back row, far right) had started to emerge.

Future Brighton captain Dave Turner was one of the successful FA Youth Cup-winning side Harvey inherited, but his first team outings were rare and he was sold to the Albion in December 1963.

Meanwhile, McGrath really established himself, featuring in 41 games in 1963-64 (Dalton played in 40) as Newcastle finished in a respectable eighth place.

The 1964-65 season saw McGrath ever-present as Toon were promoted back to the First Division, pipping Northampton Town to the Second Division championship title by one point. McGrath – “a monster of a centre-half, who was as tough as he was effective” was “the cornerstone” of the promotion side, according to newcastleunited-mad.co.uk.

McGrath retained his place in Toon’s first season back amongst the elite but the arrival of John McNamee and the emergence of Bobby Moncur started to restrict his involvement.

That pairing became Harvey’s first choice, and young Graham Winstanley was in reserve too, so, after playing only 11 games in the first half of the 1967-68 season, McGrath, by then 29, was sold to Southampton for £30,000. He’d played 181 games for United.

In Ted Bates’ Saints side, McGrath was a rock at the back alongside Jimmy Gabriel, although, as saintsplayers.co.uk records, he wasn’t too popular with opposing managers: Liverpool’s Bill Shankly accusing Southampton of playing “alehouse football”.

He went on to make 194 appearances (plus one as a sub) for Saints, before becoming youth coach at the club, part of the first team coaching staff when Southampton won the FA Cup in 1976, and then reserve team manager.

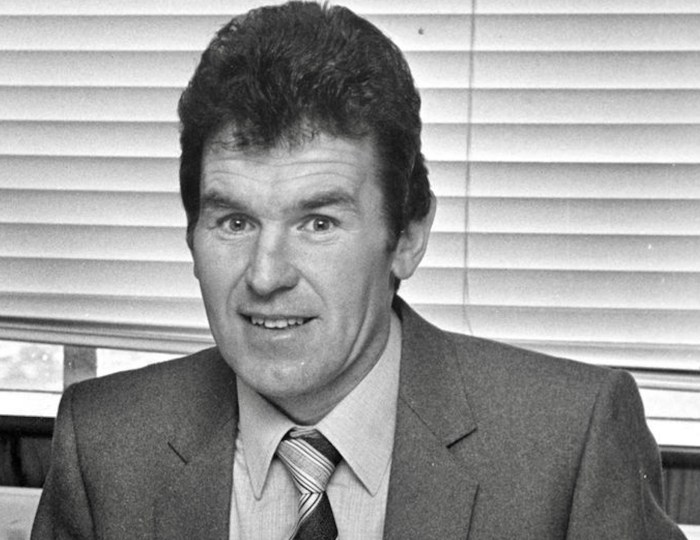

Not content with a backroom role, McGrath took the plunge into management and made his mark with two clubs in particular: managing Port Vale on 203 occasions and Preston North End in 205 matches.

According to Rob Fielding he became a cult hero at Vale Park with his unorthodox ways, once putting FIFTEEN players on the transfer list…which resulted in a six-match unbeaten run!

Winger Mark Chamberlain, who went on to play for Stoke and England, and later Brighton, was one of the young players McGrath introduced.

Long-serving Vale defender Phil Sproson, who was originally signed by former Albion midfielder Bobby Smith, rose to prominence under McGrath and said: “I’ll always be grateful because he taught me how to play centre-half.”

Fielding reckoned McGrath’s finest hour was steering Vale to promotion from the old Fourth Division in 1982-1983, even though by then he had sold Chamberlain to Stoke.

Against a backdrop of player unrest and what were perceived to be ill-judged moves in the transfer market, McGrath was sacked in December 1983 and replaced by his assistant, John Rudge.

He wasn’t out of work for long, though, and took the reins at basement side Chester City where he was in charge for just under a year. Most notably in that time, he gave future Arsenal and England defender Lee Dixon his first taste of regular football.

While success eluded him at Chester, his arrival at Preston in 1986 proved fruitful, North End striker Gary Brazil recalling: “It needed a catalyst and it needed a change and very fortunately for the club and for the players, John McGrath came walking through the door who was like a Tasmanian devil. He came in and the world changed really, really quickly for the better.”

McGrath led Preston to promotion from the bottom tier in 1987 with a squad built around Sam Allardyce and veteran Frank Worthington.

“Frank Worthington was a delight to have around and set a real high standard for a lot of us in terms of how we train,” said Brazil. “He just stunned me how he was always first out training.”

The turnround McGrath oversaw, with Deepdale crowds rising from below 3,000 to more than 16,000, rejuvenated the club and the city.

Brazil reminisced: “It was the best year of my football life that year that we got promoted. It wasn’t just an experience playing but an experience of a group of players and how well they could bond and John was integral to that. He was a very, very clever man.”

Indeed McGrath was viewed as having saved North End from the ignominy of losing their league status, the club having had to apply for re-election the season before he arrived at Deepdale.

Edward Skingsley’s book, Back From The Brink, features a black and white photograph of McGrath on its cover and tells the story of North End’s transformation under his direction.

Describing his appointment as “a masterstroke” he reckoned the club owed him a massive debt for masterminding their resurgence and subsequent stability.

“Without him, it is debatable whether Preston North End would even exist today, never mind play in the latest fantastic incarnation of Deepdale,” said Skingsley. “Thank goodness he caught Preston North End before it died.”

McGrath left Preston in February 1990 and had one last stab at management, this time with Halifax Town. He succeeded Saints’ FA Cup winner Jim McCalliog and was in charge at The Shay for 14 months but left in December 1992. Five months later they lost their league status, finishing bottom of pile.

The silver-tongued McGrath was subsequently a popular choice on the after-dinner speaking circuit and a pundit on local radio in Lancashire but died suddenly on Christmas Day 1998.

Even a crocked Chivers (by his own admission, a troublesome Achilles tendon restricted his fitness) could do a job for the Albion in an emergency, the young manager believed.

Even a crocked Chivers (by his own admission, a troublesome Achilles tendon restricted his fitness) could do a job for the Albion in an emergency, the young manager believed.

After playing regularly for Southampton’s youth side, his breakthrough came in September 1962 when just 17. He made his first-team debut against Charlton Athletic and signed as a full-time professional in the same week. He became a first-team regular the following season.

After playing regularly for Southampton’s youth side, his breakthrough came in September 1962 when just 17. He made his first-team debut against Charlton Athletic and signed as a full-time professional in the same week. He became a first-team regular the following season.