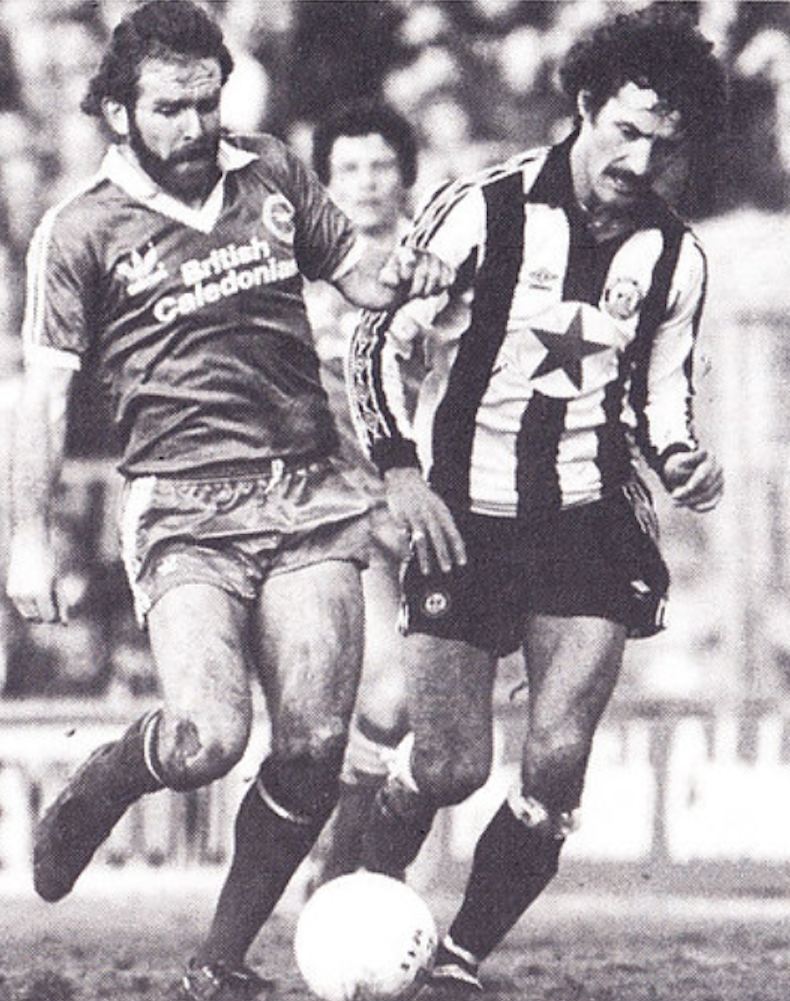

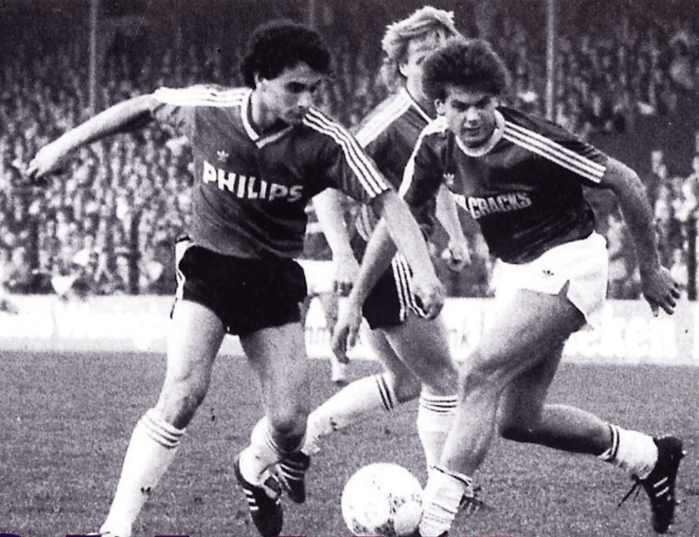

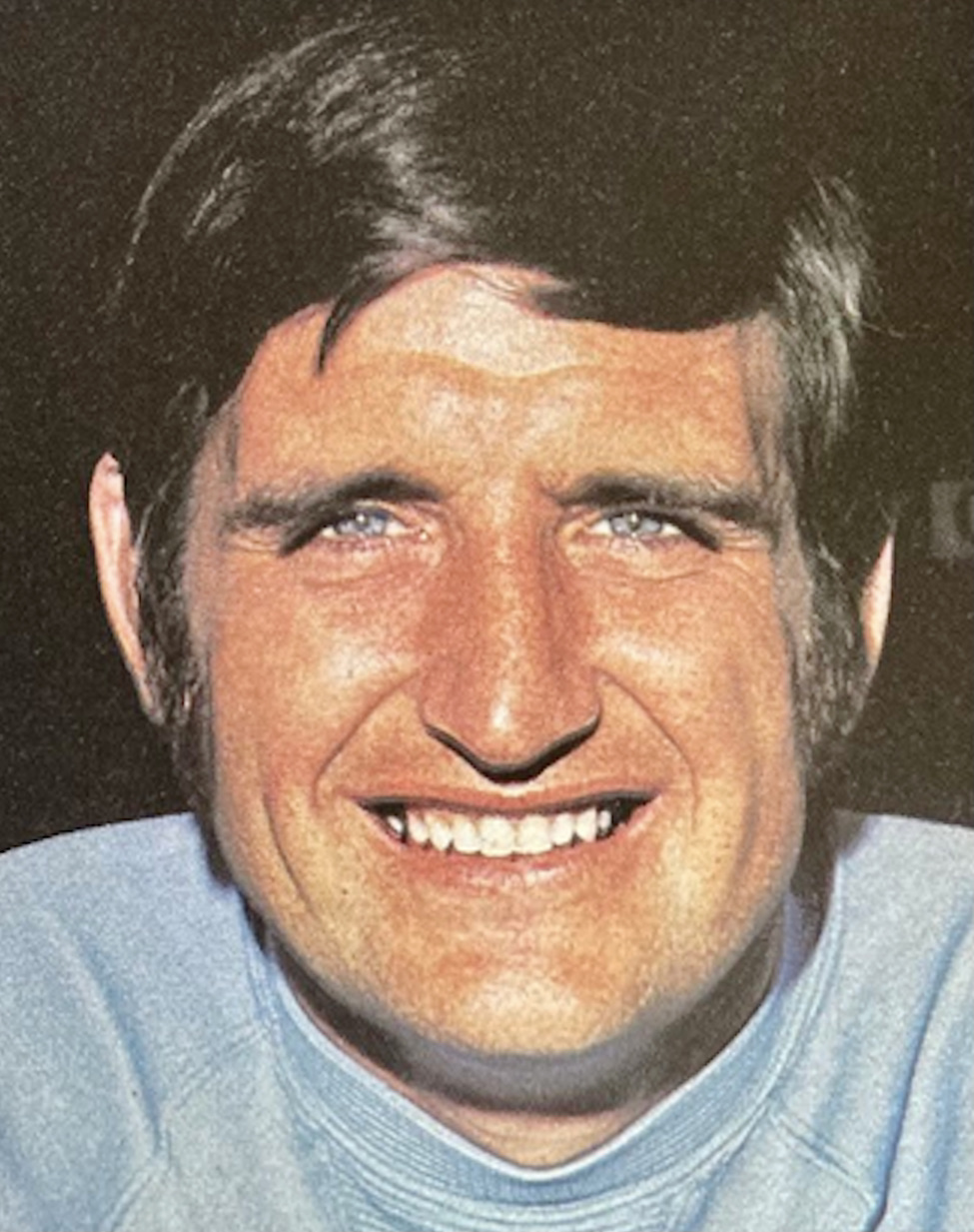

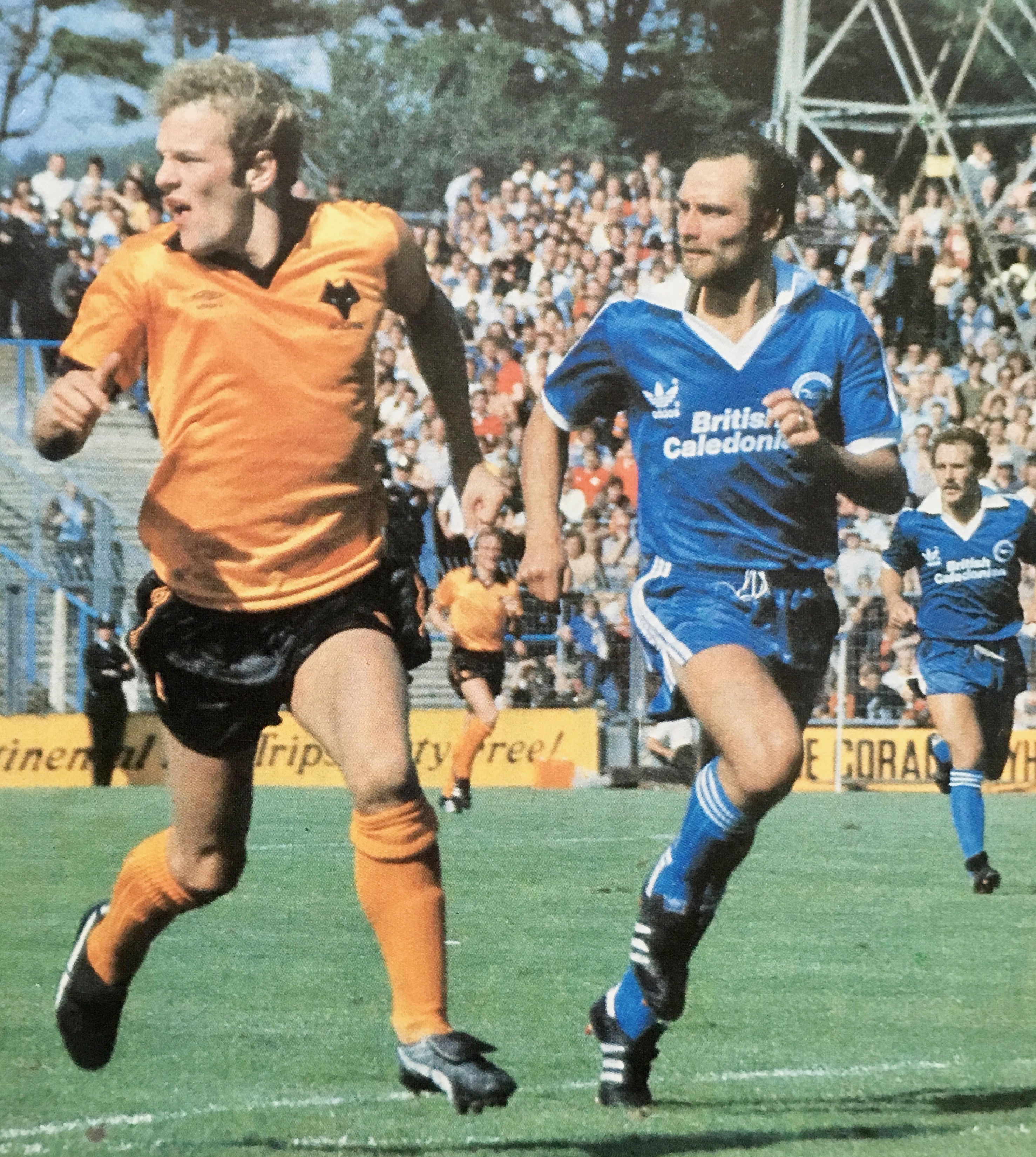

VIKING lookalike Paul Clark made a lasting impression on plenty of players with robust tackling which earned him ‘legend’ status among fans of Brighton and Southend United.

Described in one programme article as “the big bustling blond with the biting tackle”, Clark was given the nickname ‘Tank’ for his no-nonsense approach. A Southend fan lauded “his crunching tackles and never say die attitude”.

Clark himself reflected: “Wherever you go the supporters tend to like someone who is wholehearted and when it came to 50-50 challenges, or even sometimes 60-40, I didn’t shy away from too many, and the supporters just took to it.”

Giving further insight to his approach, he said: “You can go right up to the line – as long as you don’t step over it, then you’re OK.

“I used to pick up a booking during the first five or 10 minutes, then I knew I had to behave myself for the rest of the game. Despite the reputation I had, I was never sent off in over 500 games.”

Former teammate Mark Lawrenson said of him: “You would hate to have to play against him because quite often he would cut you in two. With him and ‘Nobby’ (Brian Horton) in the side, we definitely didn’t take any prisoners. One to rely on.”

A former England schoolboy international, it was said of the player in a matchday programme:

“Paul is the first to admit that skill is not his prime asset but there is no doubt as to the strength of his tackle. He is a real competitor and is also deceptively fast, being one of the best sprinters on the Goldstone staff.”

Born in south Benfleet, Essex, on 14 September 1958, Clark went to Wickford Junior School where he played for the school football team and the district primary schools’ side. When he moved on to Beauchamp Comprehensive, selection for his school team led to him playing for the Basildon Schools’ FA XI.

This in turn led to him being selected to play for England Schools at under 15 level, featuring against Scotland, Ireland, Wales, West Germany and France before going on a tour of Australia with the same age group. Contemporaries included future full time professionals Mark Higgins, Ray Deakin, Kevin Mabbutt and Kenny Sansom.

Clark left school at 16 before taking his O levels when Fourth Division Southend offered him an apprenticeship. He made his first team debut shortly before his 18th birthday in a 2-1 win over Watford.

Two months later, he won the first of six England Youth caps. He made his debut in the November 1976 mini ‘World Cup’ tournament in Monaco against Spain and West Germany alongside future full England internationals Chris Woods, Ricky Hill and Sammy Lee.

The following March, he played in England’s UEFA Youth tournament preliminary match against Wales when they won 1-0 at The Hawthorns. Sansom was also in that side. And he featured in all three group matches at the tournament that May (England beat Belgium 1-0, drew 0-0 with Iceland and 1-1 with Greece). Teammates included Russell Osman and Vince Hilaire.

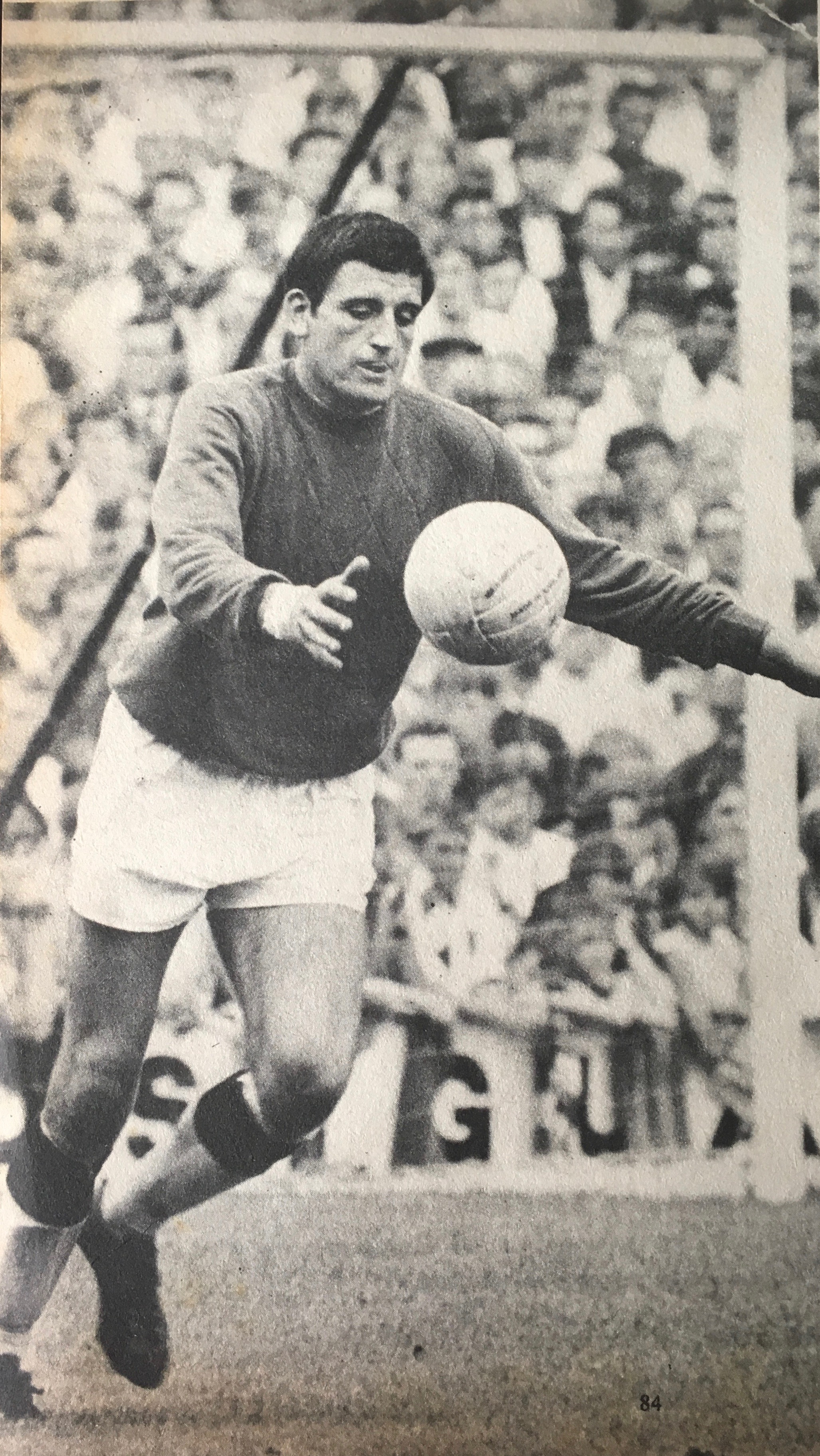

Clark was only a third of the way into his second season at Southend when Alan Mullery sought to beef up his newly-promoted Brighton side in the autumn of 1977, and, in a part exchange deal involving Gerry Fell moving to Roots Hall, Clark arrived at the Goldstone. He made his debut for the Seagulls in a goalless draw at White Hart Lane on 19 November 1977 in front of a crowd of 48,613. And he came close to crowning it with a goal but for an outstanding save by Spurs ‘keeper Barry Daines.

When Spurs visited the Goldstone later that season, Clark put in a man of the match performance and scored a memorable opener, following a solo run. A subsequent matchday programme article was suitably poetic about it.

“It showed all the qualities looked for in a player: determination, speed, skill and most of all the ability to finish….if any goal was singled out, Paul’s was certainly one to treasure.”

Albion went on to beat Spurs 3-1, although the game was remembered more because it was interrupted twice when the crowd spilled onto the pitch.

After only 12 minutes, referee Alan Turvey took the players off for 13 minutes while the pitch was cleared of Albion fans who’d sought safety on the pitch from fighting Spurs’ hooligan fans.

In the 74th minute, with Spurs 3-1 down and defender Don McAllister sent-off, their fans rushed the pitch to try to get the game abandoned. But police stopped the invasion getting out of hand and the game continued after another four-minute delay.

Clark’s goal on 16 minutes had been cancelled out six minutes later when Chris Jones seized on a bad goal kick by Eric Steele but defender Graham Winstanley made it 2-1 just before half-time.

Albion’s third goal was surrounded in controversy. Sub Eric Potts claimed the final touch but Spurs argued bitterly that Malcolm Poskett was offside.

Clark remembered the game vividly when interviewed many years later by Spencer Vignes for the matchday programme. The tenacious midfielder put in an early crunching tackle on Glenn Hoddle and after the game the watching ex-Spurs’ manager Bill Nicholson told him: “Well done. You won that game in the first five minutes when you nailed Hoddle.”

Said Clark: “I was 19 at the time so to get a pat on the back from him was much appreciated.”

It was one of three goals Clark scored in his 26 appearances that season (nine in 93 overall for Albion) but he wasn’t always guaranteed a starting berth and in five years at the club had a number of long spells stuck in the reserves.

Midfield enforcer or emergency defender were his primary roles but Clark was capable of unleashing unstoppable shots from distance and among those nine goals he scored were some memorable strikes.

For instance, as Albion closed in on promotion in the spring of 1979, at home to Charlton Athletic, Clark opened the scoring with a scorching 25-yard left foot volley in the 11th minute. Albion went on to win 2-0.

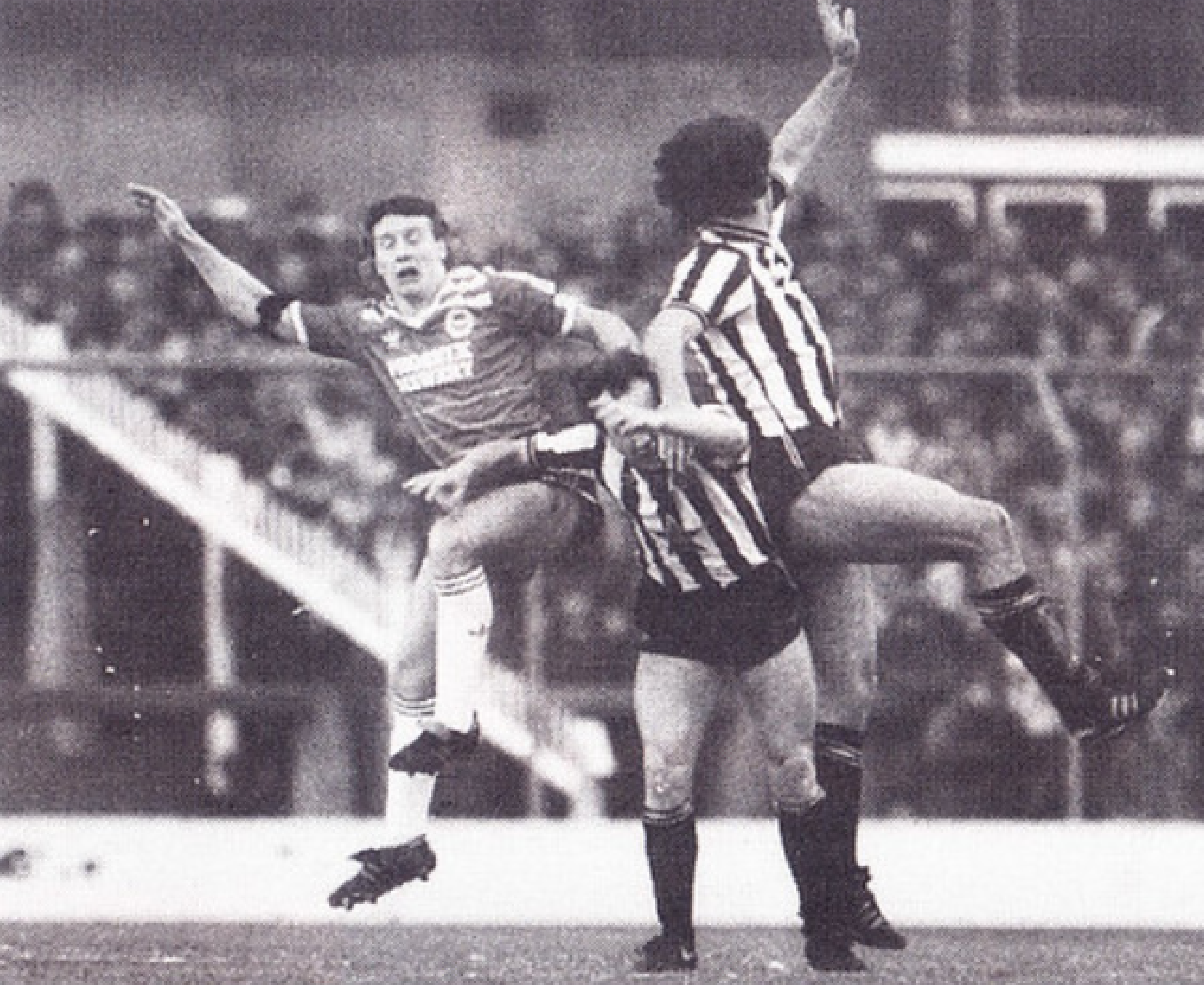

The following month, Clark demonstrated his versatility at St James’ Park on 3 May 1979 when Albion beat Newcastle 3-1 to win promotion to football’s elite level for the first time. Clark played in the back four alongside Andy Rollings because Mark Lawrenson was out injured with a broken arm.

“Not many people can say they played in a side that got Brighton up to the top flight,” said Clark. “It’s something I’m still immensely proud of.”

Once they were there, Clark missed the opening two matches (defeats at home to Arsenal and away to Aston Villa) and had an ignominious start to life at the higher level when he conceded a penalty within three minutes of going on as a sub for Rollings away to Manchester City on 25 August 1979.

Some observers thought Clark had played the ball rather than foul Ray Ranson but referee Pat Partridge thought otherwise and Michael Robinson stepped up to score his first goal for City from the resultant penalty. It put the home side 3-1 up: Teddy Maybank had equalised Paul Power’s opener but Mike Channon added a second before half-time.

Partridge subsequently evened up the penalty awards but Brian Horton blazed his spot kick wide of the post with Joe Corrigan not needing to make a save. Peter Ward did net a second for the Seagulls but they left Maine Road pointless.

Ahead of Albion’s fourth attempt to get league points on the board, Clark played his part in beating his future employer Cambridge United 2-0 in a second round League Cup match.

Three days later, he was on the scoresheet together with Ward and Horton as Albion celebrated their first win at the higher level, beating Bolton Wanderers 3-1 at the Goldstone.

It was Clark’s neat one-two with Ward that produced the opening goal and on 22 minutes, Maybank teed the ball up for Clark, who “belting in from the edge of the box, gave it everything and his shot kept low and sped very fast past (‘Jim’) McDonagh’s right hand,” said Evening Argus reporter John Vinicombe.

Gerry Ryan replaced Clark late in the game and after 12 starts, when he was subbed off three times, and four appearances off the bench, his season was over, and it wasn’t even Christmas.

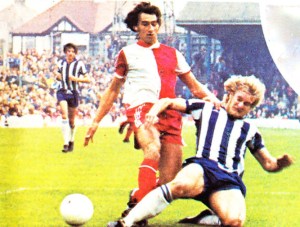

A colour photo of a typical Clark tackle (on QPR’s Dave Clement) adorned the front cover of that season’s matchday programmes throughout but he didn’t start another game after a 4-0 League Cup defeat at Arsenal on 13 November.

He was sub for the following two games; the memorable 1-0 win at Nottingham Forest and a 1-1 draw at Middlesbrough, but Mullery had signed the experienced Peter Suddaby to play alongside Steve Foster, releasing Lawrenson to demonstrate his considerable repertoire of skills in midfield alongside skipper Horton and Peter O’Sullivan.

Young Giles Stille also began to press for a place and later in the season, Neil McNab was added to the midfield options, leaving Clark well down the pecking order in the reserves. Portsmouth wanted him but he rejected a move along the coast, although he had a brief loan spell at Reading, where he played a couple of games.

But Clark wasn’t finished yet in Albion’s colours and, remarkably, just over a year after his last first team appearance, with the Seagulls struggling in 20th spot in the division, he made a comeback in a 1-0 home win over Aston Villa on 20 December 1980.

Albion had succumbed 4-3 to Everton at Goodison Park in the previous match and Mullery told the Argus: “We badly needed some steel in the side and I think Clark can do that sort of job.”

Under the headline ‘The forgotten man returns’ Argus reporter Vinicombe said Mullery hadn’t changed his opinion that Clark was not a First Division class player, but nevertheless reckoned: “Paul’s attitude is right and I know he’ll go out and do a good job for me.”

For his part, Vinicombe opined: “The strength of Clark’s game is a daunting physical presence. His tackling is second to none in the club and Mullery believes he will respond to the challenge.”

Clark kept the shirt for another nine matches (plus one as a sub), deputising for Horton towards the end of his run, but his last first team game was in a 3-1 defeat at Norwich at the end of February.

Clark remained on the books throughout Mike Bailey’s first season in charge (1981-82) but, with Jimmy Case, Tony Grealish and McNab ahead of him, didn’t make a first team appearance and left on a free transfer at the end of it.

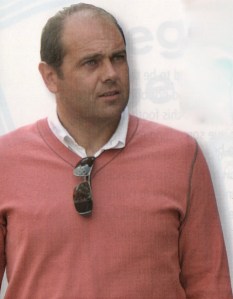

He returned to Southend where he stayed for nine years and was player-manager on two occasions. Fans website shrimperzone.com moderator ‘Yorkshire Blue’ summed up his contribution to their cause thus: “In the top five all-time list for appearances, an inspiration in four promotions, one of the toughest tacklers of all-time and a man whose commitment for his home-town club could never be doubted.”

Clark was still only 27 when he had his first spell as manager, in caretaker charge after Dave Webb had quit following a bust-up with the club chairman, and he managed to steer United to promotion back to the third tier.

When Webb’s successor Dick Bate lasted only eight games of the new season, Clark was back at the helm, in turn becoming the youngest manager in the league.

His first hurdle ended in a League Cup giant killing over top flight Derby County (who included his old teammate John Gregory) when the Us had another former Albion teammate, Eric Steele, in goal.

A Roy McDonough penalty past England goalkeeper Peter Shilton at Roots Hall settled the two-legged tie (the second leg was goalless at the Baseball Ground) which the writer described as “arguably their biggest ever cup shock”.

In the league, player-manager Clark guided Southend to a safe 17th place but it went pear-shaped the following season. Clark only played 16 games, Southend were relegated, and Webb returning midway through the season as general manager.

Back-to-back promotions in 1989-90 and 1990-91 proved to be a more than satisfactory swansong to his Southend career, and in the first of those he found himself forming an effective defensive partnership with on-loan Guy Butters in the second half of the season.

In 1990-91, he missed only six games all season as the Shrimpers earned promotion to the second tier for the first time in their history, and he had a testimonial game against Arsenal.

But, after a total of 358 games for Southend, he left Roots Hall to join Gillingham on a free transfer.

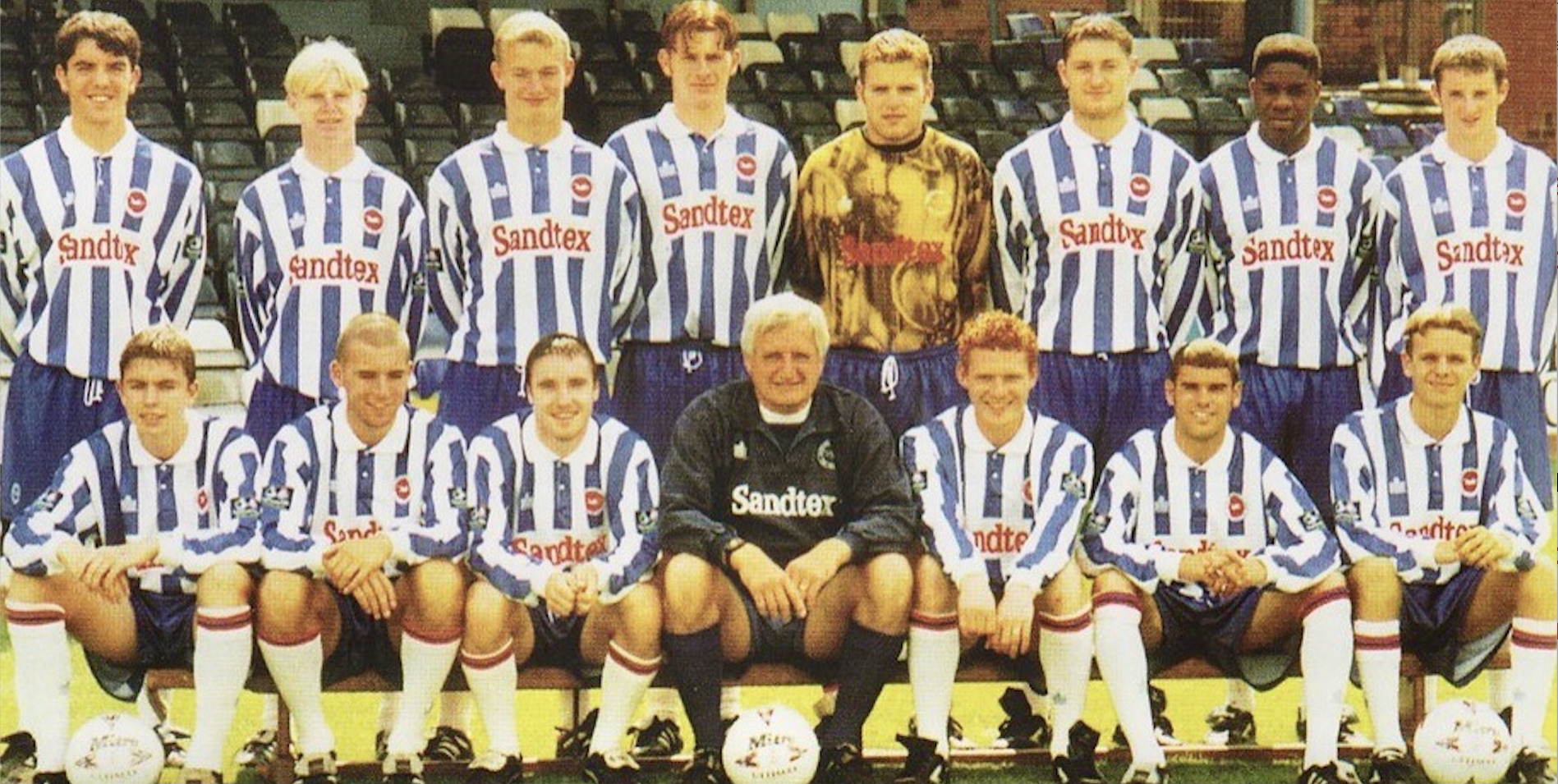

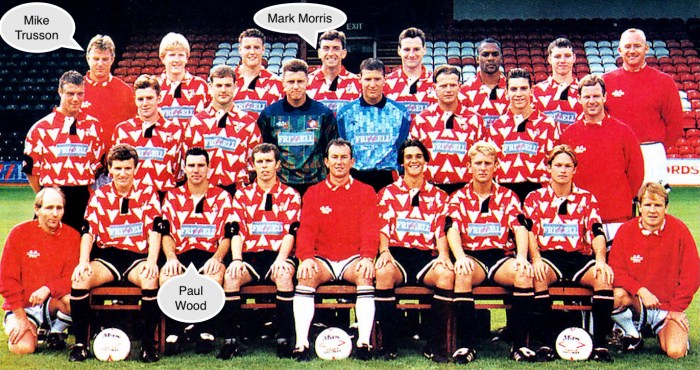

Over three seasons, he played 90 league games, and was caretaker manager in 1992, before retiring at the end of the 1993-94 season. Gillingham’s top goalscorer with 18 that season was a young Nicky Forster and other Albion connections in that squad included Mike Trusson, Paul Watson, Neil Smillie, Andy Arnott and Richard Carpenter.

After Gillingham, Clark played non-league for Chelmsford City but left to become assistant manager to Tommy Taylor at Cambridge United. In 1996 he followed Taylor in a similar role to Leyton Orient.

Southend fans hadn’t heard the last of him, though – quite literally. He became a co-commentator on Southend games for BBC Radio Essex.

In the 2009-10 season, Clark was temporarily assistant manager to Joe Dunne at Colchester United.

He stayed on and helped coach the youth team alongside John Shepherd and with Moseley fully fit was not needed for first team duty (in those days, there were no substitute goalkeepers on the bench).

He stayed on and helped coach the youth team alongside John Shepherd and with Moseley fully fit was not needed for first team duty (in those days, there were no substitute goalkeepers on the bench).

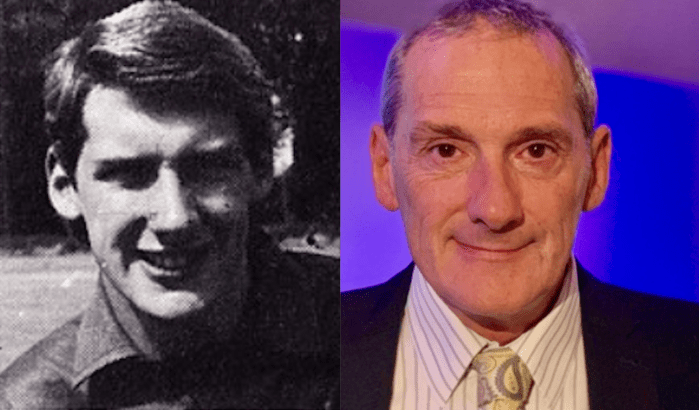

ARGUABLY the finest captain in Brighton & Hove Albion’s history went on to have a far less successful spell as the club’s manager having also been a boss at the highest level, at Maine Road, Manchester.

ARGUABLY the finest captain in Brighton & Hove Albion’s history went on to have a far less successful spell as the club’s manager having also been a boss at the highest level, at Maine Road, Manchester.