FULL-BACK John Humphrey signed for Crystal Palace in lieu of rent his previous club, newly-relegated Charlton Athletic, owed for playing home matches at Selhurst Park!

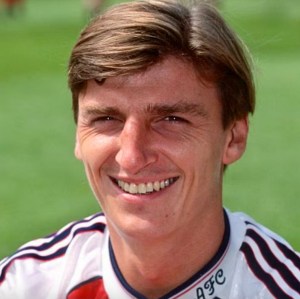

Humphrey was 29 and with more than 350 senior appearances behind him when Steve Coppell added him to an experienced defence to play alongside Eric Young and Andy Thorn in the old First Division.

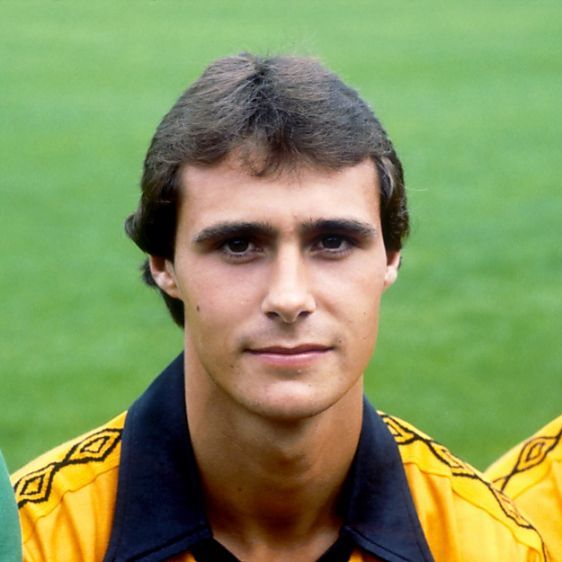

It was a level Humphrey was well used to having started out there with Wolves (where he played in the same side as Tony Towner) and at Charlton in a defence that included Colin Pates.

All that came before Humphrey came to Albion’s rescue in the dark days of the 1996-97 season, as I recounted in my 2020 blog post about him.

This time I’m highlighting his time at Selhurst Park, which he spoke about at length in a January 2023 interview with cpfc.co.uk.

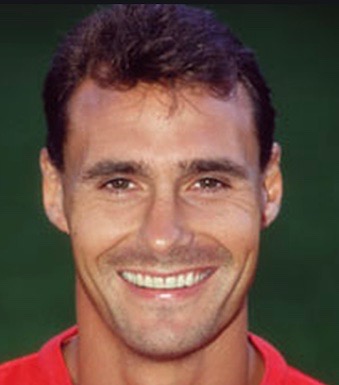

“I saw myself as one of the senior players,” Humphrey remembered. “We had the likes of Richard Shaw coming through and Gareth [Southgate] coming through and we signed people like Chris Coleman and Chris Armstrong. Alongside that we had some experience with Eric Young and [Andy] Thorny, so I hoped I fitted in to part of the jigsaw.

“[The challenge] for me was getting used to the style of play, because at that time I know Stevie was not so much direct but he wanted to get the ball forward as early as possible because of the threat of [Ian] Wright and [Mark] Bright. So, it took me a while to get used to that.

“I do remember after a few games Stevie dropped me for a game to say: ‘This is what I want you to do.’ Then he put me back in… I was part of his restructuring and in that first year it worked out very well.”

So much so that at the end of his first year at the club Palace reached third – their highest league finish in history – and won the Zenith Data Systems trophy (otherwise known as the Full Members’ Cup) at Wembley, beating Everton 4-1.

Humphrey was still playing in the Premier League at the age of 34 and clocked up 203 appearances for the Eagles before briefly returning to Charlton for the 1995-96 season, moving on to Gillingham and then helping out his old Charlton teammate Steve Gritt in Brighton’s hour of need.

Revered at Charlton, chicagoaddick.com wrote of him: “In the five seasons he patrolled our right side of defence he missed only one league game and faced the best wingers and strikers playing in the country at that time: Barnes, Waddle, Le Tissier, Lineker, Rush, Aldridge, Beardsley, Fashanu.

“Maybe it was because we stood in the decrepit Arthur Wait Stand but Humphrey was fantastic to watch up close. Graceful, but strong in the tackle. He was a quick-thinker and a quick mover. He would glide down the right wing and put in some peaches of a cross.”

Humphrey won three consecutive player of the year awards (1988, 1989, 1990) – an honour no other Charlton player has received.

By the time he arrived at Brighton, he was 36 and had played close on 650 professional matches.

“Steve wanted me because I was experienced, could get the players organised and was able to talk them through matches,” Humphrey told the Argus in a January 2002 interview. “He knew I was steady, reliable and dependable, that nine games out of ten I’d play pretty well and that I would give 100 per cent.

“It was a lot of pressure but I’d been through a few promotions (three) and relegations (six) with Wolves, Charlton and Crystal Palace.” He continued: “The stressful situations I had gone through with those other clubs had given me experience of how to try and keep a season alive.

“I could do a job for Brighton and I felt I did that and the team turned out to be good enough to hang on. It was one of the biggest achievements of my career.”

He added: “It might have been going out of the frying pan of Gillingham into the fire at Albion but I’m glad I made the jump.”

Humphrey looked back fondly on those difficult times and told the newspaper: “They have great fans and the Goldstone was always packed for the home games.

“You couldn’t help but be lifted by the crowd. The team couldn’t win away, but managed to win at home. So, one win every two games was decent and led to that eventful day at Hereford.”

When he left the Albion as part of a cost-saving measure the following season, he turned semi-pro and played initially for Chesham in the Ryman League premier division, then Carshalton, Dulwich Hamlet and Walton and Hersham.

“Having come from the professional ranks to semi-pro it was difficult to adjust to the different standards like some of the attitudes of players to training for instance,” Humphrey said. “Also, I found the training itself wasn’t that enjoyable.

“I remember at Walton and Hersham turning up for a session, but we weren’t allowed on the pitch and had to do a road run. That was frustrating and I begun to think that maybe there were other things in life than just playing football.”

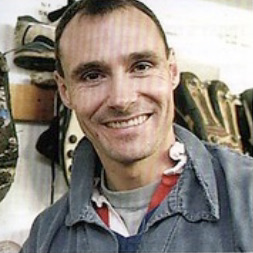

Former teammate Pates was his conduit to a new career as a teacher at Whitgift School in Croydon, where ex-Palace and Chelsea midfielder Steve Kember also joined them.

“I knew Colin from Charlton when we roomed together,” he explained. “I was aware he was at the school and he said he needed help for after-school sessions and asked me to come along.

“So I did and the football took off at the school and I got involved in other sports like rugby and basketball and got a full-time job there.”

He also retained his links with Charlton, coaching their under-15 team, and told the Argus in that 2002 piece: “I deal with privileged kids at Whitgift who may go on to be doctors, lawyers or solicitors while at Charlton the kids usually aren’t so privileged.

“To a lot of them, football is a way of making something of themselves. It gives me a great buzz when one of the Charlton youngsters makes positive progress.”

Humphrey later moved on to become head of football at Highgate School in north London.